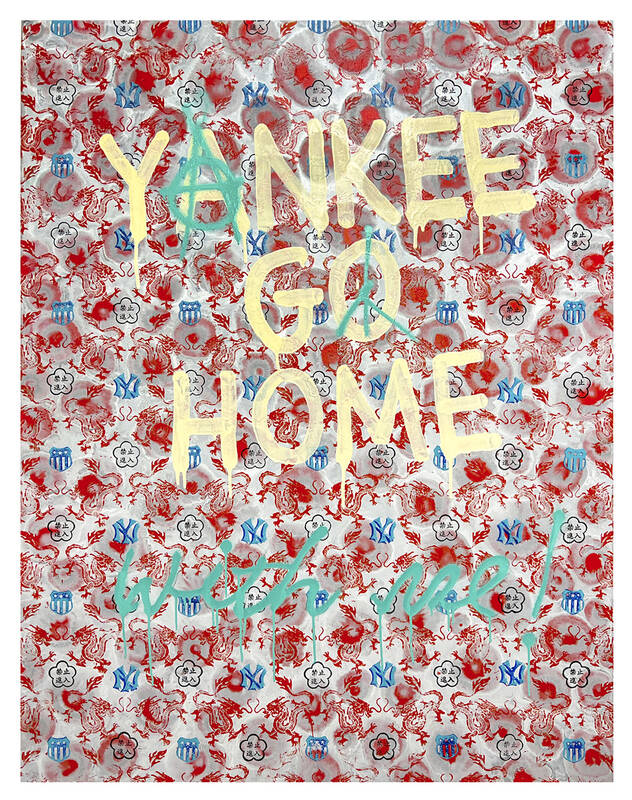

It may seem odd to use a painting with “Yankee Go Home!” in bright gold letters as the main visual for an exhibition titled “To Taiwan” (致台灣).

But on closer inspection, it actually says “Yankee Go Home with me,” a reference to the gender-queer rock musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch. The layered background is composed of overlapping and repeating symbols which, for artist Jason Cole Mager, represent the US, New York, China, Japan and Taiwan.

First visiting Taiwan in 2013, the American painter’s initial work drew more from his fascination with the nation’s complex history and identity politics. But as Mager began to increasingly see Taiwan as his home, he shifted to exploring his personal relationship with the country.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Mager tells the Taipei Times that the “Yankee Go Home” phrase is about him being overly sensitive about whether he can ever fit in with Taiwanese society, and the movie reference allows him to be playful.

“It’s also talking about something real; Americans are known to [go into other countries] and mess around with things, and that’s where that slogan comes from,” he says. “As an artist, is it patronizing for me to come in and talk about your history, and try to tell you about it?”

Visitors can decide for themselves at Mager’s first solo exhibition, which opens tomorrow at 99 Degree Art Center (九十九度藝術中心) in Taipei’s Beitou District. The selections trace Mager’s evolution throughout the years and runs until March 26.

Photo courtesy of Jason Cole Mager

DIGGING FOR SYMBOLS

With an MFA from New York’s Hunter College, the Indianapolis-born Mager’s work today is nothing like the more traditional figure paintings he made more than 20 years ago. He had wanted to move into more abstract experimentation, but found it difficult to find context to inspire the work.

Around 2005, he found some photos of his grandfather taken during World War II, and one particular image of their platoon dressed up in jest as German soldiers (probably after killing them) — complete with swastika armbands — stood out to him.

Photo courtesy of Jason Cole Mager

“It was such a powerful image, the idea of simple symbols lined up next to each other,” he says. “I spent a while trying to figure out how to use this. I was super uncomfortable using the swastika, and I ditched it after a year or so.”

Like many New Yorkers, Mager converted one of his bedrooms into a guesthouse for tourists. At the urging of a Taiwanese guest, he visited Taiwan for the first time in 2013, and it drew him in.

The idea of “simple symbols” came back to him here, first through things like personal name chops (he was excited to legally use his the first time last week when he got married). His studio overlooks the former Taihoku Prison grounds (Taihoku is the Japanese colonial era name for Taipei), where he eventually learned that 14 Allied soldiers were executed in June 1945, right before the end of World War II.

Photo courtesy of Jason Cole Mager

This connected Taiwan’s history to his personal experiences, and he began to dig deeper into the nation’s rich past and find more symbols such as emblems and flags that he could employ to explore “what is Taiwan and who are the Taiwanese.”

The symbols often cover the entire canvas like wallpaper and overlap with each other, sometimes requiring some scrutiny.

Mager often uses the plum blossom to represent Taiwan, as well as the Republic of Formosa tiger flag.

Photo courtesy of Jason Cole Mager

“The plum blossom did arrive after 1949 with the KMT, but it’s somewhat neutral,” he says.

The US shows up in the eagle emblem or the US Aid logo. China is a dragon, Japan a rising sun. Ming warlord Cheng Cheng-kung’s (鄭成功, also known as Koxinga) seal, as well as the Dutch East India Company logo also appear. And he’s planning a series that includes Indigenous motifs.

BECOMING TAIWANESE?

Mager’s earlier paintings were more direct, referring to events like the American bombing of Taipei’s Longshan Temple or the sociopolitics behind the ubiquitous peony cloth. A few have the Republic of China (ROC) sun emblem on them, such as Setting of the Rising Sun, which juxtaposes it with the Japanese Empire’s sun to show the transition between the two periods.

“Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) supporters have accused me of being critical of them, while Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) people say I’m glorifying the KMT,” Mager says. “You can take what you want from it; the whole point is to start a conversation.”

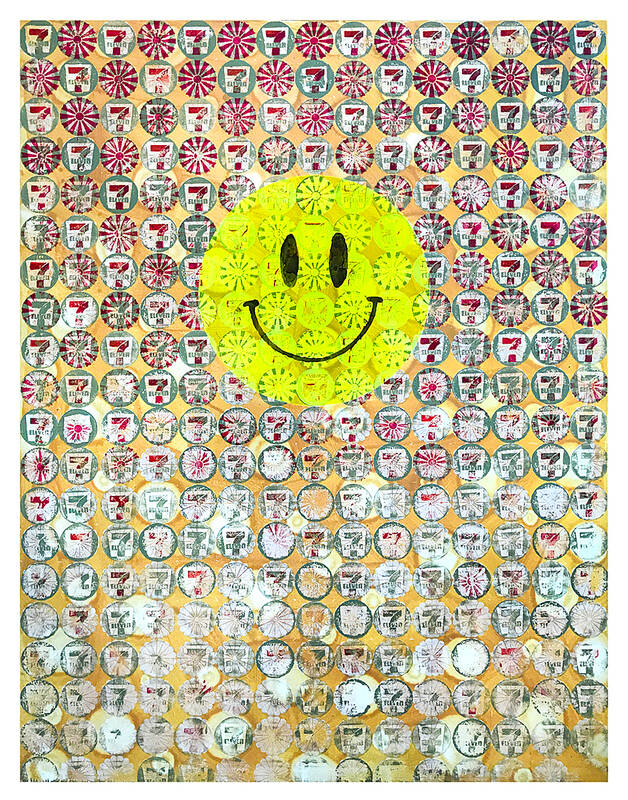

Corporate Colonization places 7-Eleven logos and the rising sun emblem side by side, with a giant smiley face that appears on plastic bags handed out by franchises in the US in the center. Mager says it’s just a humorous attempt to highlight that the most ubiquitous store in Taiwan is owned by a Japanese company.

After Mager read Taiwan’s 400 Year History by Su Beng (史明), he gained a deeper understanding of the identity politics between people whose families arrived before and after 1949.

“Where do I fit in here?” he said of himself. “How long do I have to be here before I can say I’m Taiwanese? It sounds absurd just to hear that, and maybe you just don’t?” he muses.

One painting has the Chinese words wailaizhe (外來者, “outsider”) on it.

“If you really want to get into it, unless you’re indigenous, we’re all outsiders,” he says. “Taiwan’s always been about people coming in and trying to set up.”

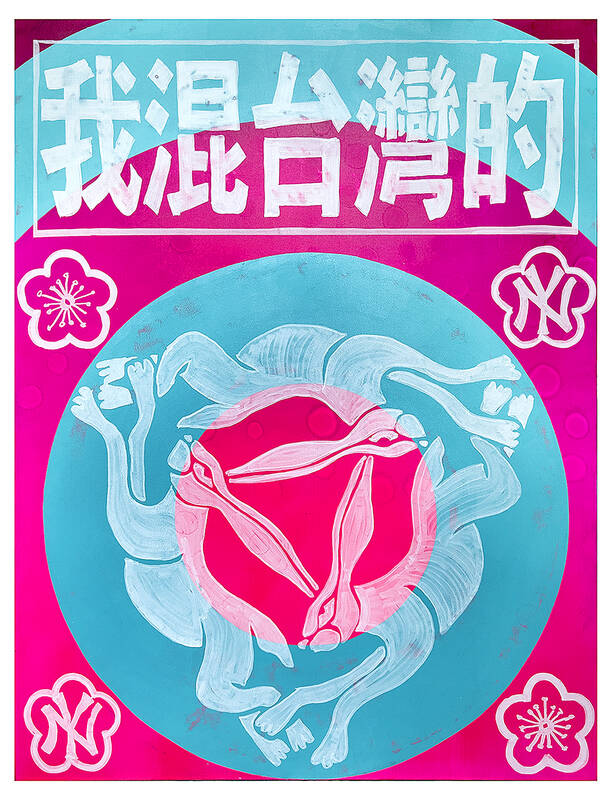

Mager’s latest creation, a Year of the Rabbit with the Chinese phrase, wo hun Taiwan de, (我混台灣的) sounds more sure: The tongue-in-cheek slang term of Taiwanese pride is hard to translate, but to Mager, it means, “I’m bound to Taiwan.”

In Taiwan there are two economies: the shiny high tech export economy epitomized by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) and its outsized effect on global supply chains, and the domestic economy, driven by construction and powered by flows of gravel, sand and government contracts. The latter supports the former: we can have an economy without TSMC, but we can’t have one without construction. The labor shortage has heavily impacted public construction in Taiwan. For example, the first phase of the MRT Wanda Line in Taipei, originally slated for next year, has been pushed back to 2027. The government

July 22 to July 28 The Love River’s (愛河) four-decade run as the host of Kaohsiung’s annual dragon boat races came to an abrupt end in 1971 — the once pristine waterway had become too polluted. The 1970 event was infamous for the putrid stench permeating the air, exacerbated by contestants splashing water and sludge onto the shore and even the onlookers. The relocation of the festivities officially marked the “death” of the river, whose condition had rapidly deteriorated during the previous decade. The myriad factories upstream were only partly to blame; as Kaohsiung’s population boomed in the 1960s, all household

Allegations of corruption against three heavyweight politicians from the three major parties are big in the news now. On Wednesday, prosecutors indicted Hsinchu County Commissioner Yang Wen-ke (楊文科) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), a judgment is expected this week in the case involving Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and former deputy premier and Taoyuan Mayor Cheng Wen-tsan (鄭文燦) of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is being held incommunicado in prison. Unlike the other two cases, Cheng’s case has generated considerable speculation, rumors, suspicions and conspiracy theories from both the pan-blue and pan-green camps.

Stepping inside Waley Art (水谷藝術) in Taipei’s historic Wanhua District (萬華區) one leaves the motorcycle growl and air-conditioner purr of the street and enters a very different sonic realm. Speakers hiss, machines whir and objects chime from all five floors of the shophouse-turned- contemporary art gallery (including the basement). “It’s a bit of a metaphor, the stacking of gallery floors is like the layering of sounds,” observes Australian conceptual artist Samuel Beilby, whose audio installation HZ & Machinic Paragenesis occupies the ground floor of the gallery space. He’s not wrong. Put ‘em in a Box (我們把它都裝在一個盒子裡), which runs until Aug. 18, invites