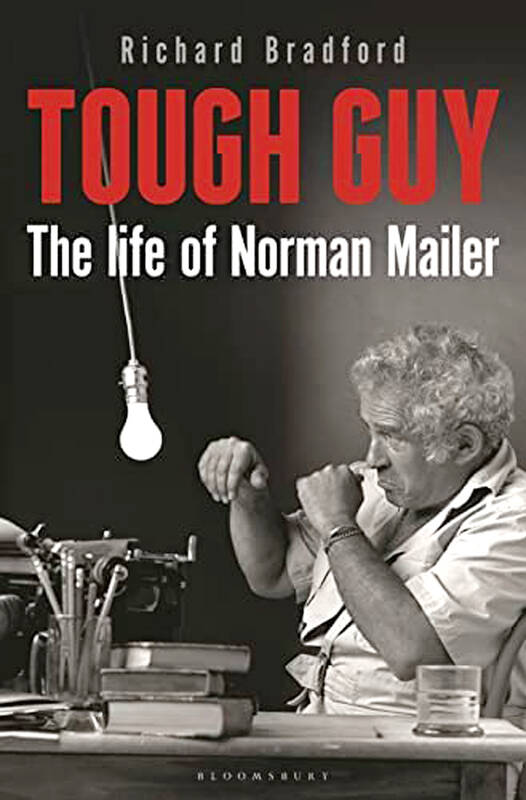

Norman Mailer — when not boozily brawling, dosing himself with hallucinogenic drugs and serially fornicating — was a man with a sacred mission. He regarded himself as a prophet, bringing bad news to a society that had settled into consumerist complacency during the 1950s. Americans believe that they live in God’s own country; Mailer alerted them to “the possible existence of Satan,” who might be residing next door and quietly assembling a private arsenal for use on Judgment Day.

Although Mailer looked up at the sky with “religious awe,” what he saw there was a mushroom-shaped cloud that he called “the last deity.” Humanity, he declared, was reeling towards self-destruction. Now that his centenary has arrived (he was born Jan. 31, 1923), I dare anyone — and that includes Richard Bradford, the author of this sensationalized canter through his life — to say that he was wrong.

True, Mailer was an obnoxious loudmouth. In episodes that Bradford documents with slavering relish, he conducted literary disputes by butting his colleagues: “Once again words fail you,” drawled the coolly disdainful Gore Vidal after one such attack.

Domestically, Mailer was a wife-beater and almost a murderer: taunted as a “faggot” by the second of his six spouses, he stabbed her with a penknife at a drunken party, just missing her heart. After an early infatuation with President Kennedy, whose fatal ride through Dallas in an open car he applauded as a moment of existentialist bravado, his politics lurched towards fascism. He commended Hitler for providing Germans with an outlet for their “energies,” although — as a man who bragged about his own bulbous, fizzily fertile “cojones” and the indefatigable piston of his penis — he pitied the Fuhrer for possessing only one testicle and having to rely on masturbation.

Mailer intended to write the Great American Novel and he went into athletic training for the epic feat

If this all sounds marginally deranged, that’s because America provoked Mailer to such outbursts.

Bradford treats him as a morbid anomaly, but he was not alone. William S Burroughs actually killed his wife, which Mailer didn’t quite manage to do; Hunter S Thompson fulminated against the country in a spirit of coked-up loathing and after shooting himself in the head had his ashes fired from a mountain-top cannon; in a bardic rant aptly entitled Howl, Allen Ginsberg screamed with joy about being sodomized by saintly motorcyclists. In Rebel Without a Cause, James Dean watches in a planetarium as our planet expires in a burst of fiery gas and Mailer, who, as Bradford usefully points out, was psychoanalyzed by Robert Lindner, the author of the book from which Dean’s film took its title, also testified to a “forthcoming apocalypse.”

The critic Lionel Trilling said that “for purposes of his salvation, it is best to think of the artist as crazy, foolish, inspired;” it was the mania of Mailer and the others that made their rages so cathartic.

Like many contenders before him, Mailer intended to write the Great American Novel and he went into athletic training for the epic feat. On an African junket to report on one of Muhammad Ali’s prizefights he heard a lion roar in the jungle, which he thought brought him close to Hemingway, the hunter of wild game; in Mexico, in another homage to his idol, he even took fumbling lessons as a matador. Once, in a boat off Provincetown, he sighted a whale: did that equip him to compete with Ahab’s metaphysical vendetta in Melville’s Moby-Dick?

Bradford’s contention is that Mailer’s obstreperous life was the novel he didn’t have the time or the talent to produce. It’s a flippant misjudgment: his best work, in any case, is his nonfiction, in which he studied the “psychic havoc” incited by contemporary events.

In response to the killing of the Kennedy brothers he elaborated the kind of nuttily ingenious conspiratorial plot that now proliferates on social media. He treated Marilyn Monroe as a goddess sacrificed to her worshippers and in doing so he came to see that celebrity is a kind of death cult, dooming those it deifies.

Reflecting on the 1969 moon landing, he wondered how this human incursion might have disturbed the quiescence of outer space. Mailer’s abiding subject was America’s id, “the dream life of the nation,” and he ventured intrepidly into that irrational underground.

None of this matters to Bradford, who after spending a few pages on Mailer’s war novel The Naked and the Dead dismisses all of his subsequent work, which he variously calls unreadable, ludicrous, incomprehensible, atrocious and hilariously terrible; critics who disagree are accused of writing gibberish.

This kind of “wet job” — a CIA euphemism for assassination — is Bradford’s speciality: he recently doled out the same treatment to Patricia Highsmith and his publisher eggs him on by calling him “merciless” and announcing that in this book he “strikes again.” He has nothing but contempt for Mailer, although he is creepily curious about his sexual forays; at the end he hurtles through his subject’s sad final years in a few perfunctory sentences, anxious to be rid of him. Even at his maddest, Mailer deserves a better memorial.

Oct. 21 to Oct. 27 Sanbanqiao Cemetery (三板橋) was once reserved for prominent Japanese residents of Taipei, including former governor-general Motojiro Akashi, who died in Japan in 1919 but requested to be buried in Taiwan. Akashi may have reconsidered his decision if he had known that by the 1980s, his grave had been overrun by the city’s largest illegal settlement, which contained more than 1,000 households and a bustling market with around 170 stalls. Fans of Taiwan New Cinema would recognize the slum, as it was featured in several of director Wan Jen’s (萬仁) films about Taipei’s disadvantaged, including The Sandwich

“Wish You Luck is not just a culinary experience, it’s a continuation of our cultural tradition,” says James Vuong (王豪豐), owner of the Daan District (大安) Hong Kong diner. On every corner of Kowloon, diners pack shoulder-to-shoulder over strong brews of Hong-Kong-style milk tea, chowing down on French Toast and Cantonese noodles. Hong Kong’s ubiquitous diner-style teahouses, known as chachaanteng (茶餐廳), have been a cultural staple of the city since the 1950s. “They play an essential role in the daily lives of Hongkongers,” says Vuong. Wish You Luck (祝您行運) offers that same vibrant melting pot of culture and cuisine. In

Much noise has been made lately on X (Twitter), where posters both famed and not have contended that Taiwan is stupid for eliminating nuclear power, which, the comments imply, is necessary to provide the nation with power in the event of a blockade. This widely circulated claim, typically made by nuclear power proponents, is rank nonsense. In 2021, Ian Easton, an expert on Taiwan’s defenses and the plans of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to break them, discussed the targeting of nuclear power plants in wartime (“Ian Easton On Taiwan: Are Taiwan’s nuclear plants safe from Beijing?”, April 12, 2021). The

Artificial intelligence could help reduce some of the most contentious culture war divisions through a mediation process, researchers say. Experts say a system that can create group statements that reflect majority and minority views is able to help people find common ground. Chris Summerfield, a co-author of the research from the University of Oxford, who worked at Google DeepMind at the time the study was conducted, said the AI tool could have multiple purposes. “What I would like to see it used for is to give political leaders ... a better sense of what people ... really think,” he said, noting surveys gave