May 9 to May 15

Poisoned dagger in hand, Korean national Cho Myeong-ha pushed aside the cheering schoolchildren and lunged at Prince Kuni Kuniyoshi’s roofless car. He swiped once and missed. As the car sped up, Cho threw the dagger. But its unclear what happened next on the streets of Taichu (Taichung) on May 14, 1928.

According to post-war Korean sources, the dagger grazed the prince and inflicted a minor injury before hitting the driver in the back. The poison soon spread through Kuniyoshi’s body, and he died the following January in Tokyo. Japanese accounts, however, maintain that Cho missed once more, and the prince died later from an unrelated illness.

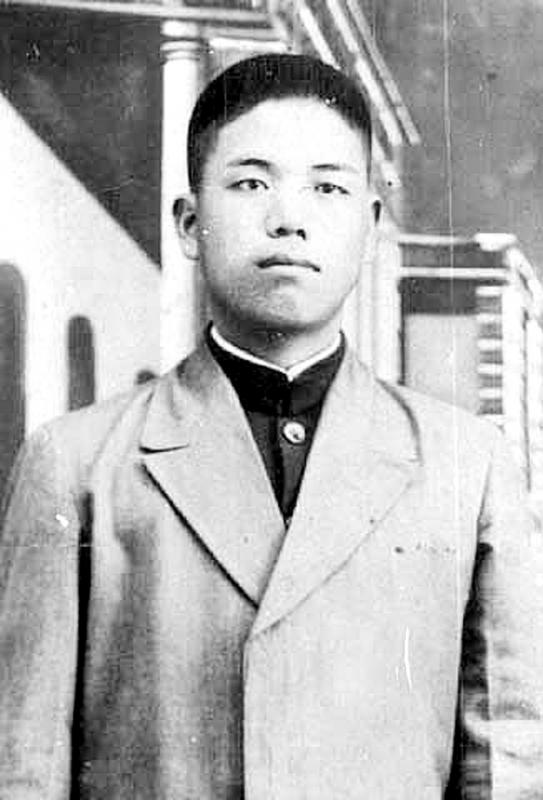

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chen Wei-han (陳煒翰) offers another explanation in the book, Japanese Royals Visit Taiwan (日本皇族台灣行旅): the prince emerged unharmed but was rattled by the close call, dying later from psychological duress. He was 56 years old.

Cho reportedly told the crowd after his arrest: “Don’t be afraid, I am only taking revenge for the Korean Empire. Long live Korea!”

He tried to commit suicide by ingesting morphine, but vomited it out and survived. The 23-year-old was sentenced to death and executed in Taipei on Oct. 10.

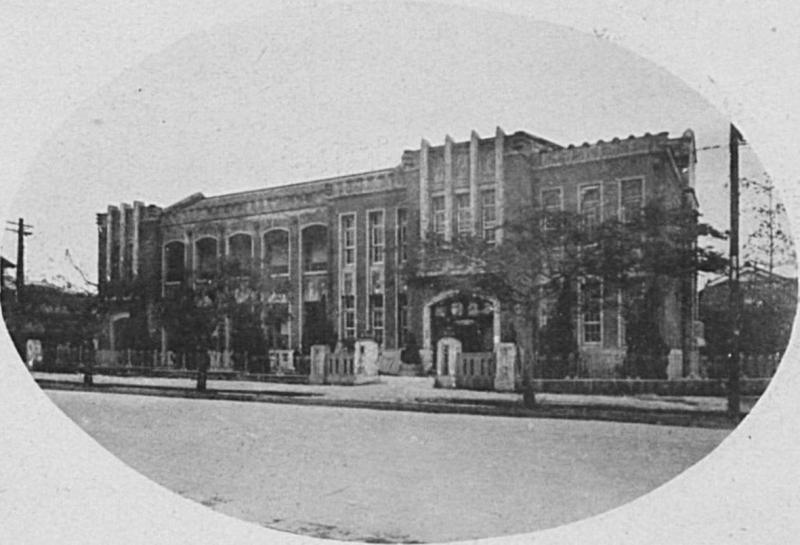

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The incident led to the high-profile resignations of Taiwan governor-general Mitsunoshin Kamiyama, chief secretary Fumio Koto, police commissioner Bunpei Motoyama and Taichu Prefecture governor Tsuzuku Sato.

DIFFERING MOTIVES

Cho was born in 1905, the year Korea became a protectorate of Japan. Five years later, Japan formally annexed his homeland. Former Korean emperor Gojong’s sudden death in 1919 was widely speculated to be due to poisoning by the Japanese, sparking massive protests on March 1, which were brutally suppressed.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Unrest erupted again on June 10, 1926, with the death of King Sunjong, this time mostly involving students. Cho had just gotten married and secured a job as secretary with the local government, but he soon quit and allegedly traveled to Japan to plan an uprising, as strict surveillance made any further action impossible back home.

Again, accounts differ depending on which side is telling the story. His verdict states that he was simply unhappy with the low pay of his job and went to Japan to further his studies. He was having trouble making ends meet and set his sights on Taiwan, which he heard was a “land of abundance” with many opportunities for economic development.

However, Taiwanese and Korean accounts indicate that Taiwan was just a pit stop on Cho’s way to join the Korean government-in-exile in Shanghai. Unable to find a job in Taipei, he traveled to Taichung and started working on a Japanese-owned tea farm. He became bitter that Koreans earned only half the salary of the Japanese, and his boss repeatedly reneged on his promise of a raise, even docking his pay at times.

According to a Taichung Cultural Affairs Bureau document, a “bitter and disgruntled” Cho was planning to leave for Tainan on May 12, 1928, but after his salary was withheld again, his frustrations finally boiled over.

Court documents state that he bought the dagger to commit suicide, but after hearing that Kuniyoshi was to visit Taichung the following day, he decided to assassinate the royal. Modern sources, however, indicate that he acquired and learned how to use the weapon specifically to assassinate the prince.

MILITARY TRIP

Japanese royals often visited Taiwan to strengthen the colony’s loyalty towards the emperor. It was also a chance for colonial officials to show off their achievements. The frequency of these visits greatly increased after crown prince Hirohito made the journey in 1923.

Kuniyoshi first visited Taiwan in 1920 as the head of the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai, a martial arts organization, to attend the annual meet for the local chapter. A career military man, his profile further rose when his daughter was betrothed to Hirohito in 1922. He was promoted to general the following year.

Kuniyoshi’s second visit was mostly to inspect the military forces stationed in Taiwan. Things were growing tense as the Japanese Army prepared to clash with Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) leader Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) National Revolutionary Army in China’s Shandong Province, which was under Japan’s sphere of influence.

The Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) detailed the prince’s visit, from his landing on April 27 to his departure on June 1, but did not mention of the attack. After spending several days in Alishan, where he was treated to “song and dance” by the indigenous people, he headed to Taichung to meet local officials and visit the city’s military facilities and academy.

On the night of May 13, Kuniyoshi watched the then-famous Changhua fireworks. The next morning, his eight-car motorcade drove through Taichung to a cheering crowd on its way to the train station to catch a special train bound for Taipei. Cho had a six-minute window to strike, and made his move just as the cars slowed down to make a left turn.

AFTERMATH

The Taichung Cultural Affairs Bureau document maintains that Cho’s dagger grazed the prince, causing a minor cut, but other sources dispute this. He was arrested after fleeing the scene and failing to kill himself.

Kamiyama, the governor-general, attempted to resign after the incident, but then-prime minister Giichi Tanaka instructed him to remain at his post and keep the assassination a secret.

The incident was finally made public on June 14, when Cho was transferred from the Taichung prison to Taipei. Kamiyama was replaced the next day.

On July 18, Cho was sentenced to death. His verdict states that this was not a planned assassination, but an impromptu act of a desperate man who was mistreated by his employers. In any case, he chose Kuniyoshi because he was obviously bitter about his country’s occupation.

Ikeda Masahide, the tea shop owner, was reportedly investigated several times after the assassination attempt. Even though he tried to change his store’s name and offered various promotions, his business failed and he was eventually forced to close up and leave Taiwan.

Cho was hanged on Oct. 10. His alleged last words were, according to the Taichung document: “I have long been ready for this moment of death. My only regret is that I will no longer live to see my country regain its independence. In the other world, I shall continue to seek independence for Korea. Long live Korea!”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the