Per recent trends, young worshippers have been offering KFC buckets to Fuhu Temple’s (伏虎宮) Tiger Lord. Whether they know it or not, this tiger won’t be devouring any of it, as he is vegetarian.

Temple director Hsu Ping-tsung (許炳宗) says that’s because the feline god in his place of worship — one of just a handful in Taiwan with the Tiger Lord as a principal deity — is of Buddhist origins. Before its deification, it was the mount of one of the 18 Arhats.

“The Tiger Lord told me that his generals and soldiers still need to eat meat in order to have the strength to carry out his deeds,” Hsu says. “So you can’t tell the believers to stop bringing meat.”

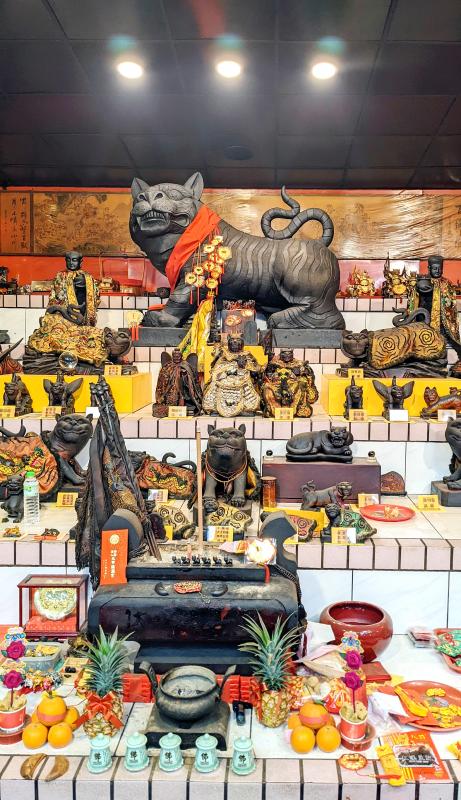

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

What about eggs, which have traditionally been the go-to offering for Tiger Lords?

“With all this talk of ovo-lacto-vegetarianism and the sort, I became confused too,” Hsu says. “I asked the Tiger Lord, but he didn’t answer me. But one thing he insists on is having enough water,” pointing to the red urn of water at the altar.

Although belief in the Tiger Lord has existed in Taiwan for centuries, its appeal among young people has grown in recent years as it has appeared in all sorts of popular media, most notably the hit 2017 film The Tag-Along 2 (紅衣小女孩2). And with it being the Year of the Tiger, Fuhu Temple, located on a remote hill in New Taipei City’s Shihding District (石碇), has been flooded with worshippers since the days running up to the Lunar New Year holiday.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Hsu says it was crowded in the previous Year of the Tiger 12 years ago too.

“In other temples, it might be like this during occasions like the birthday of the main deity, whether it be Matsu or San Taizi,” he says. “But we have an entire Year of the Tiger.”

FIVE COLORS

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Most people come here to pray for money, and Hsu says that the temple is popular with bankers, real estate agents, moneylenders and salespeople. Most Tiger Lords in Taiwan are “Earth Tigers,” which lie under the altar of other deities, he says, and there are very few “Heavenly Tigers” in Taiwan that get their own high seats.

Heavenly Tigers are able to draw from the treasury of the heavens and reward people with money according to the good karma they accrue in life by doing good deeds, Hsu says, and they’re especially effective during the Year of the Tiger.

Each stack of spirit money is accompanied by one or many tiny stuffed tigers containing the Tiger Lord’s incense ash, most of them yellow. Hsu explains that each year, the Tiger Lord picks a color representing the Five Elements — this year happens to be yellow, which represents wealth.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

The Tiger Lord has forbidden Hsu to sell the stuffed tigers — even though he believes that the cute, handmade mascots are highly marketable — and people can only obtain them through buying spirit money to pray. The different colored ones on the table are from previous years, as many regular worshippers like to bring them back and pass them through the incense smoke to rejuvenate their power.

Hsu says manufacturers press him each year to reveal the color as early as possible, but he can’t until he “hears” from the Tiger Lord.

“It’s not a voice,” he says. “You just feel it.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Hsu believes that each year’s color will predict that year’s events, so he’s positive that this year will be one of great prosperity. Last year’s color was black, which means gathering positivity. Hsu says with the outbreak, it made sense to lay low and build up one’s strength, and this year will be time to thrive.

In 2020, the color was white, which represented change and opportunity. Hsu interprets that as how the COVID-19 pandemic forced many businesses to reinvent the way they operate to survive.

FINDING ITS WAY

Hsu can still remember the exact moment three decades ago when the Tiger Lord successfully pushed its way out of Taipei’s Dizang Temple (地藏庵). This Tiger Lord was originally worshiped on its own, but its fierceness caused much unrest and violence in the area, and a monk suggested that it needed a human-based god to keep it under control.

“In the city, the tiger attacks everyone,” Hsu says. “The mountain is their natural territory where they can tell good people from bad people.”

Hsu’s elder brother was the Tiger Lord’s spirit medium then, and one day the deity expressed its wish to strike out on its own — with the approval of the Jade Emperor, the Taoist pantheon’s supreme deity. The temple’s directors agreed, and prepared to carve a new Tiger Lord statue and provide funds for its new temple.

But the Tiger Lord refused the offer, as he wanted the original statue to leave with him. The directors suspected Hsu’s brother of making this up, and finally agreed to leave the matter up to divination blocks. If they received 36 casts that landed on “yes” in a row, they would let the Tiger Lord go.

“I was there, and with each casting, my heart leaped,” Hsu says. Nobody could believe it as the 36th throw spun around and landed in the Tiger Lord’s favor.

“The spirit medium immediately carried the statue out of the temple.”

The Tiger Lord also turned down money offered by the temple, Hsu says, taking only the plaque that hangs over the main altar today.

“The highway wasn’t built yet and there was nothing here back then, just jungle,” Hsu says.

The brothers started looking into who owned the land and, as luck would have it, it belonged to Hsu’s grandfather.

The Tiger Lord told the Hsu family that when the highway reached Shihding, he would slowly be able to unleash his powers. Freeway No. 5 was completed in 2000, and worshippers gradually began to flock to the temple.

However, Hsu says after his brother died in 2007 and he took over, the mostly-elderly worshippers suddenly stopped coming. But the Tiger Lord asked him to be patient, that he would eventually bring a new wave of believers to the temple.

The turning point came in 2010, the last time the Year of the Tiger rolled around.

“He told me that I mustn’t feel defeated or obligated to make any changes. If I just waited here and served him well, then fate would bring people in.”

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,