The international community of China human rights watchers lost a legendary figure last month with the passing of Robin Munro, who was one of the key Western observers of the 1989 Tiananmen student protests in Beijing. He died on May 19 in Taipei at age 67.

Tributes have poured forth from ranking journalists and top figures at Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, China Labor Bulletin and London’s School of Oriental & African Studies (SOAS), calling Munro a “legend,” who set the “gold standard” for human rights documentation in the post-Tiananmen era.

“Munro was [Human Rights Watch’s] first researcher on China. He was the last known Westerner to leave Tiananmen Square. He did pathbreaking work on China’s horrible orphanages and on labor rights,” tweeted Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch.

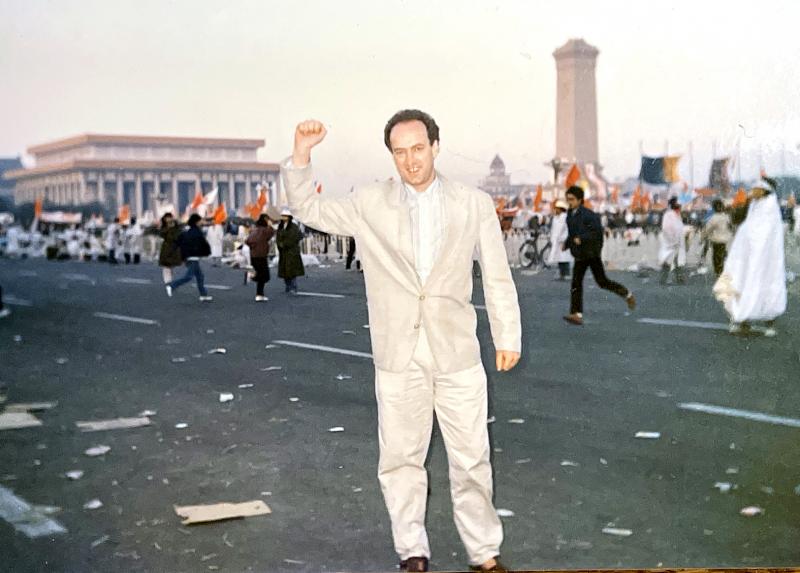

Photo: David Frazier

“Robin helped many Chinese dissidents, who might otherwise have died in prison, to gain their freedom. I was one of them,” wrote Tiananmen democracy activist Han Dongfang (韓東方).

“His work on China human rights issues was hugely important,” tweeted Bloomberg reporter Benjamin Robertson.

HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN CHINA

Photo: Bloomberg

Over the last three decades, Munro authored groundbreaking reports on China’s organ harvesting, abuses in orphanages, psychological torture of political prisoners and early rights abuses in Xinjiang.

Munro came into the human rights field when China was largely sealed off to the West and its human rights issues were little understood. He began his career in 1979 with Amnesty International in London, then in 1987 moved over to Human Rights Watch in New York. In early 1989, Human Rights Watch sent him to Hong Kong as its first dedicated China researcher and office director.

Within months of the posting to Hong Kong, student demonstrations erupted in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, and Munro traveled north to witness them first hand. He is acknowledged as the last Western observer to leave the square early on the morning of June 4, 1989, staying on to witness the arrival of the People’s Liberation Army. Munro’s documentation of that event, and interviews he gave on Western TV news programs, became crucial to the world’s understanding of what was happening on the ground.

Photo courtesy of Huang Pao-lien

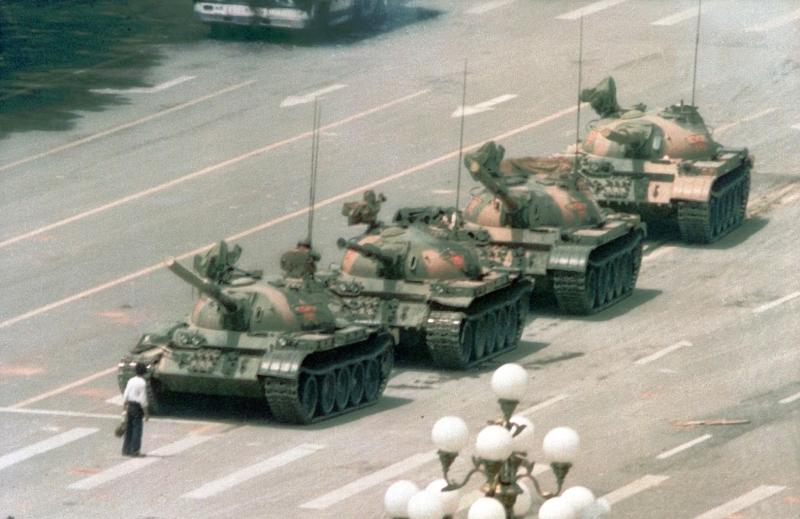

A recent obituary from SOAS observed that Munro’s “account made the important point that it was not in fact students who were massacred in the Square, but rather the citizens of Beijing — the laobaixing (老百姓) — who were supporting the students in the streets outside the Square and were slaughtered there.”

In 1990, on Tiananmen’s first anniversary, Munro explained in an article in the US magazine The Nation, “A massacre did take place — but not in Tiananmen Square, and not predominantly of students. The great majority of those who died… were workers, or laobaixing (“common folk” or “old hundred names”), and they died mainly on the approach roads in western Beijing.”

Later in the article he explained that the reason these common citizens were “mercilessly punished [was] in order to eradicate organized popular unrest for a generation.”

Photo: AP

“Journalism may be only the rough draft of history,” wrote Munro, “but if left uncorrected it can forever distort the future course of events.”

“I think that a key part of Robin’s success as an activist was his sense of responsibility, as a scholar, to the truth as supported by evidence. Despite his passion... he never exaggerated,” observed Donald Clarke, a specialist in Chinese law at George Washington University and one of Munro’s closest personal friends.

MAN OF THE PEOPLE

Robin Munro was born in London on June 1, 1952. At the age of six, he moved with his family to Scotland, where his father was a lecturer at the Veterinary School of Glasgow University.

His mother’s line included three generations of missionaries in China, going back to the 1800s. His own mother was born in 1918 in Swatow, China — present day Shantou, Guangdong Province — but as political upheaval swept China in the 1920s, the family returned to Edinburgh in 1925.

Munro began his studies at Edinburgh University in 1969, but dropped out for some time to live in a hippie commune on the Balearic island of Formentera, just next to Ibiza. In Scotland, he also drove a public bus, an item he kept on his CV for years as a nod to his labor credentials. When he returned to school in 1974, he changed his academic tack and began studying Chinese.

He traveled to China for the first time as a visiting student from 1977 to 1979, a period which perfectly straddled the end of the Cultural Revolution. In his first year at Peking University, his classmates and roommates were workers, peasants and soldiers assigned to the university by the Communist Party, while in his second year he studied with intellectuals returning from rural communes, who had been sent down by Chairman Mao Zedong (毛澤東).

In the decade following the Tiananmen massacre, Munro helped numerous fleeing Chinese dissidents attain asylum in the West.

He also “did pathbreaking research” — published as reports and books — “on China’s psychiatric abuse of political prisoners, abuses in orphanages and organ harvesting of convicts. He also broke new ground reporting on Inner Mongolia, the laogai (勞改, “reform through labor”) detention system in Xinjiang and repression of Catholics in Hebei province,” according to a statement by Human Rights Watch.

“All of these works constituted the first serious and scholarly examination of the problems they addressed,” wrote Clarke.

One of the Chinese dissidents Munro helped, Li Jinjin (李進進), tweeted, “It shocked me, the sad news that my friend Robin [is] gone. He met me after I was released from Qincheng Jail in Beijing in…1991. He helped me come to the United States in…1993.”

PLIGHT OF ACTIVISTS

Munro chronicled the plight of Li and other activists in the 1993 book Black Hands of Beijing, which he co-authored with George Black.

Another dissident assisted by Munro was one of the founders of the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation, the aforementioned Han Dongfeng, whom Munro became friends with through frequent visits to the workers encampment in Tiananmen Square.

Following the 1989 crackdown, Han was imprisoned for two years and placed in a cell with tuberculosis sufferers. Han eventually lost a lung to the disease and might have died had Munro not lobbied for his release and helped arrange medical treatment.

In 1994, Han had settled in Hong Kong and there founded an NGO, China Labor Bulletin advocating for labor rights in China. Munro began working with him at the organization a decade later in 2003.

“Robin worked tirelessly over the past two decades to provide legal assistance for tens of thousands of Chinese workers seeking justice through the court system,” Han wrote in a recent tribute.

“Many of them had suffered terrible work injuries, contracted occupational diseases or were desperate to get the back pay owed for months, even years, of hard labor. Many workers faced imprisonment for defending their legal rights. These workers and their families should know that it was this Scotsman, Robin Munro, who helped them obtain justice.”

In 2004, Munro married the Taiwanese writer Huang Pao-lien (黃寶蓮), today a well-known author of 16 books of fiction and non-fiction.

PERSONAL CONNECTION

In 2011, the couple moved from Hong Kong to Taipei, after Munro was set upon by medical issues. For a decade, he managed to beat his illness, living happily in semi-retirement on the slopes of Yangmingshan, north of Taipei.

I met him there last year, where he helped me make a digital recording of old analogue audio tape, using one of his vintage reel-to-reel tape players.

Munro was a high-end audiophile, who spoke gleefully of his German hand-crafted turntable arm, his 1950s French amplifier and his unbelievable music collection, which included some of the first ever stereo recordings on analogue tape. I now regret that I never had the chance to return so that he could play them for me — he had of course made the generous offer, and spoke with vast and marvelous knowledge on the nuances of high fidelity.

Munro was taken by a sudden illness in April and died on May 19 at Taipei Veterans Memorial Hospital. He is survived by his sister Sandra and wife Huang Pao-lien, who was by his side to the last.

Munro influenced an entire generation of human rights workers in Asia, and recent numerous tributes acknowledge this legacy.

Their sentiments are best summed up in the eulogy of his longtime friend, Donald Clarke: “For many in the human rights community, his passing marks the loss of a giant figure. For his wife, sister and friends, it marks the loss of a part of themselves. For everyone, his life is a reminder of what matters in this world. In Shakespeare’s words, ‘His life was gentle, and the elements mixed so well in him that Nature might stand up and say to all the world, This was a man.’”

Words of the Year are not just interesting, they are telling. They are language and attitude barometers that measure what a country sees as important. The trending vocabulary around AI last year reveals a stark divergence in what each society notices and responds to the technological shift. For the Anglosphere it’s fatigue. For China it’s ambition. For Taiwan, it’s pragmatic vigilance. In Taiwan’s annual “representative character” vote, “recall” (罷) took the top spot with over 15,000 votes, followed closely by “scam” (詐). While “recall” speaks to the island’s partisan deadlock — a year defined by legislative recall campaigns and a public exhausted

In the 2010s, the Communist Party of China (CCP) began cracking down on Christian churches. Media reports said at the time that various versions of Protestant Christianity were likely the fastest growing religions in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The crackdown was part of a campaign that in turn was part of a larger movement to bring religion under party control. For the Protestant churches, “the government’s aim has been to force all churches into the state-controlled organization,” according to a 2023 article in Christianity Today. That piece was centered on Wang Yi (王怡), the fiery, charismatic pastor of the

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality