April 19 to April 25

Taipei’s Dalongdong Baoan Temple (大龍峒保安宮) was in a sorry state following the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) retreat to Taiwan in 1949. About 200 refugees and military dependents had taken over the 119-year-old structure and set up camp in makeshift dwellings.

When writer Wu Chao-lun (吳朝綸) moved to Dalongdong in 1950, he saw “little incense burning; it was extremely crowded … and there was barely any space to sit. They washed their clothes with dirty water and hung them up still dripping. This is not only blasphemous, but unsanitary.”

Photo: Wang Min-wei, Taipei Times

To save the temple, locals put together a restoration committee in 1952, with wealthy businessman Lin Kung-chen (林拱振) at the helm. Lin spent over a decade reviving and promoting Baoan Temple, most famously leading in 1957 a scripture chanting group made up entirely of female workers from his factory on a nationwide tour to generate interest.

In 1966, the Taipei City Government finally stepped in and helped relocate the squatters, and only then could Lin fully focus on restoring the temple to its former glory.

Founded by settlers from Quanzhou, China, Dalongdong Baoan Temple is one of more than 200 shrines in Taiwan dedicated to Baoshengdadi (保生大帝), the Taoist god of medicine.

Photo: Liu Hsin-de, Taipei Times

Taiwan was a notorious “land of pestilence” before Japanese colonization in 1895, and settlers from Fujian often looked toward Baoshengdadi for protection.

Before Baoshengdadi became a deity, he was a scholar, exorcist and healer surnamed Wu (吳) who was allegedly born in Baijiao (白礁), Quanzhou in 979. Wu’s birthday falls on next Monday, and temples across Taiwan are hosting events to celebrate the occasion. Baoan Temple’s festivities began last Thursday, but the major ceremonies will commence on Saturday.

HOLY DOCTOR

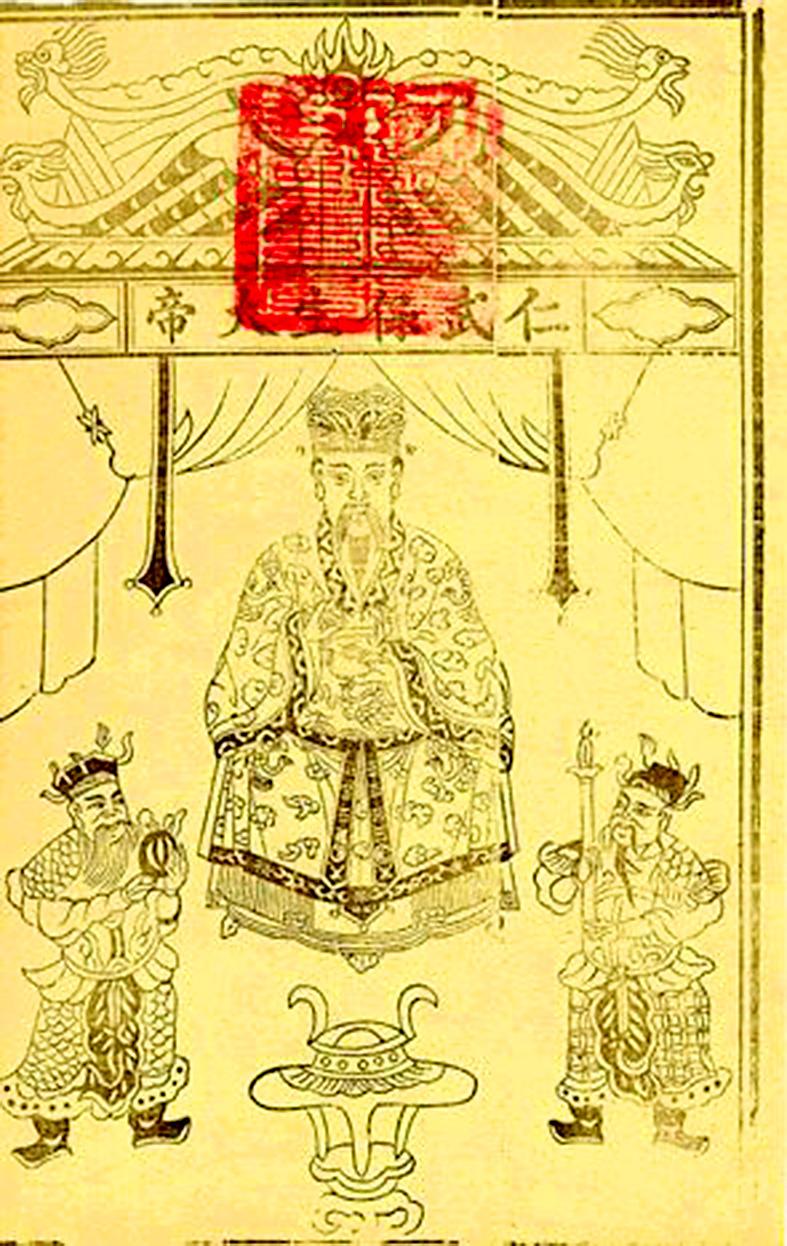

Photo courtesy of Baoan Temple

Two ships set out in 1756 from Quanzhou at the same time, each carrying an effigy of Baoshengdadi. The sailors agreed that the first statue to reach today’s Dalongdong area in Taipei would be worshipped at the soon-to-be-complete Baoan Temple as the “grand master” (老祖) and the other one the “second master” (二祖).

The smaller effigy was accompanied by statues of the mighty Santaizi and Black Tiger General deities, and perhaps due to their protection, that boat reached the port of Tamsui without a hitch. The other vessel was blown off course in a storm and landed in today’s Chiayi County, and the settlers traveled north by land. They were stopped by countless worshippers along the way, and it took several months for them to reach their destination.

Baoan Temple was first built in 1746 as a crude wooden structure, but in 1755, the settlers decided to pool their money to construct a proper temple. It was completed in 1760, upon which an even larger Baoshengdadi statue was carved and designated as “third master.” In 1805, locals began rebuilding the temple in today’s location, which took 25 years to complete.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

There are many versions of Wu’s origins. According to the Dalongdong Baoan Temple, he was said to be a child genius with a photographic memory who was well-versed in traditional Chinese medicine as a teenager. At the age of 17, he learned how to slay and exorcise demons from the Taoist deity Xi Wangmu (西王母), and at 24 he passed the imperial examinations and served as an official. He later retired to the mountains near his hometown and became widely known for his miraculous healing abilities.

Wu died at the age of 58 and became a deity. The first temples to worship him both appeared in 1151 in Baijiao and neighboring Qingjiao (青礁), which some accounts list as his birthplace instead. By the 1400s, worship had spread to neighboring Zhangzhou, Xiamen as well as Kinmen, which today boasts at least 15 temples dedicated to Wu.

In 1419, the Ming Dynasty’s Wen Empress fell ill with a breast ailment that no royal physicians were able to heal. Wu reportedly appeared in her dream as a Taoist priest and taught her the remedy, and she soon recovered. The empress sent someone to investigate this priest’s identity and traced him to Baijiao, where she learned of Wu’s feats. She then bestowed upon him the title “The Savior from Heaven, the Miraculously Healing, Wonderful and Wise True Lord, the Ageless, Limitless Great Emperor that Protects Life” (恩主昊天醫靈妙惠真君萬壽無極保生大帝) and granted him a dragon robe and a palace.

LEGENDS ACROSS TAIWAN

The earliest Baoshengdadi temple in Taiwan appeared in the Tainan area during the Dutch occupation. When Ming loyalist Cheng Cheng-kung attacked the Europeans in 1662, many of his soldiers hailed from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou, and they often placed Baoshengdadi effigies on their warships. After their victory, these soldiers settled in Taiwan and founded Baoshengdadi temples wherever they went.

Weng Ya-chin (翁雅琴) writes in the paper, Study of Baoshengdadi Legends in Taiwan (台灣保生大帝傳說研究) that the tales surrounding the deity focused less on his origins as Wu, but more on how each temple was founded as well as the various miracles the deity performed.

Like the Dalongdong Baoan Temple, many temples started as crude wooden shrines, and it usually took some sort of apparition or feat for locals to build a proper structure. Weng writes that these stories were often embellished to encourage people to donate money for construction. When funds ran out during renovations, the temple would often attribute good fortunes — such as a bountiful harvest — to Baoshengdadi, and the money flowed in again.

The deity’s powers apparently reach beyond the realm of medicine. Legend has it that the deity in Tainan’s Xingan Temple (興安宮) helped the villagers drive out a corrupt official, while the one in Changhua’s Xianan Temple (咸安宮) instructed the locals how to fend off a bandit invasion.

When the People’s Liberation Army shelled Kinmen in 1958, fishers near Tainan’s Cihji Temple (慈濟宮) heard ducks quacking all night, and they believed that this was Baoshengdadi sending a “duck army” across the Taiwan Strait to reinforce the troops.

DECLINE AND REVIVAL

Baoshengdadi temples boomed during the 19th century — about 80 were built across Taiwan between 1795 and 1895. The Dalongdong Baoan Temple was almost destroyed in 1859 during a conflict between Quanzhou and Zhangzhou settlers, who were often at odds with each other. As a Zhangzhou mob descended from Shilin to attack the temple one evening, a group of beggars hanging out inside started making loud noises with sticks, causing the invaders to flee, thinking that it was heavily guarded.

The Japanese limited Taiwanese religious activity after its arrival, and between 1896 and 1904, the Dalongdong Baoan Temple was used as an elementary school. It fell into disarray over the years, and in 1917 local elites collected money to fix it up, and it experienced a brief revival over the next decade.

In 1930, to observe the 100th anniversary of the current structure’s completion, devotees made a pilgrimage to Baijiao to pay their respects. However, activity had pretty much ceased by the end of Japanese rule due to World War II and lack of leadership.

Under Lin’s guidance, the temple began to prosper again even before he got rid of the squatters — in 1960, the Taipei mayor publicly reprimanded him for hosting extravagant ceremonies that ran against the government’s austerity movement.

Baoan Temple continued to expand and renovate over the decades, and Baoshengdadi’s annual birthday party is considered one of the “big three” temple festivals in Taipei.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Under pressure, President William Lai (賴清德) has enacted his first cabinet reshuffle. Whether it will be enough to staunch the bleeding remains to be seen. Cabinet members in the Executive Yuan almost always end up as sacrificial lambs, especially those appointed early in a president’s term. When presidents are under pressure, the cabinet is reshuffled. This is not unique to any party or president; this is the custom. This is the case in many democracies, especially parliamentary ones. In Taiwan, constitutionally the president presides over the heads of the five branches of government, each of which is confusingly translated as “president”

Sept. 1 to Sept. 7 In 1899, Kozaburo Hirai became the first documented Japanese to wed a Taiwanese under colonial rule. The soldier was partly motivated by the government’s policy of assimilating the Taiwanese population through intermarriage. While his friends and family disapproved and even mocked him, the marriage endured. By 1930, when his story appeared in Tales of Virtuous Deeds in Taiwan, Hirai had settled in his wife’s rural Changhua hometown, farming the land and integrating into local society. Similarly, Aiko Fujii, who married into the prominent Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家) in 1927, quickly learned Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) and

The Venice Film Festival kicked off with the world premiere of Paolo Sorrentino’s La Grazia Wednesday night on the Lido. The opening ceremony of the festival also saw Francis Ford Coppola presenting filmmaker Werner Herzog with a lifetime achievement prize. The 82nd edition of the glamorous international film festival is playing host to many Hollywood stars, including George Clooney, Julia Roberts and Dwayne Johnson, and famed auteurs, from Guillermo del Toro to Kathryn Bigelow, who all have films debuting over the next 10 days. The conflict in Gaza has also already been an everpresent topic both outside the festival’s walls, where

The low voter turnout for the referendum on Aug. 23 shows that many Taiwanese are apathetic about nuclear energy, but there are long-term energy stakes involved that the public needs to grasp Taiwan faces an energy trilemma: soaring AI-driven demand, pressure to cut carbon and reliance on fragile fuel imports. But the nuclear referendum on Aug. 23 showed how little this registered with voters, many of whom neither see the long game nor grasp the stakes. Volunteer referendum worker Vivian Chen (陳薇安) put it bluntly: “I’ve seen many people asking what they’re voting for when they arrive to vote. They cast their vote without even doing any research.” Imagine Taiwanese voters invited to a poker table. The bet looked simple — yes or no — yet most never showed. More than two-thirds of those