Back in the 1950s, the lifeguards of Bondi Beach, Sydney, were not only charged with rescuing surfers and scanning for sharks. In their role as “beach inspectors” they were also responsible for ensuring that swimsuits conformed to New South Wales state regulations.

At least 7.6cm of fabric was required over the thigh, no navels were to be exposed and shoulder straps had to be “sturdy.”

One of the best-known beach inspectors was Aubrey Laidlaw, who had already laid down the law when the first bikini debuted on the beach in 1946. By the turn of the 1960s, the “Bikini Wars” were in full swing. Laidlaw and his inspectorate patrolled the beach with tape measures, methodically escorting scantily clad women away. But one morning in 1961, he saw something that astonished even him — men in Speedos. He called the police and had them arrested for indecent exposure.

Photo: AP

Laidlaw and his tape measure are long gone, but in certain backwards-looking jurisdictions — Britain, America — the Speedo-wearing male remains an object of discrimination and ridicule. No item in the male wardrobe is so exposing. None demands such brazenness, such balls. But neither is any so liberating, or so practical, say truly committed Speedo-wearers.

“You have way more freedom in Speedos,” says Luke Day, editor of GQ Style, who has no fewer than 51 pairs “in current circulation,” including a denim pair by Rufskin and a knitted pair by Maria Aristidou, though mostly he prefers plain white.

“I like as much exposed skin for tanning as possible. And they’re so much less restrictive than shorts. That’s the whole point of them. That’s why Tom Daley wears them to dive in,” Day says.

Photo: AP

As Daley himself once explained to Graham Norton, who wondered why his trunks had to be quite so tight: “If you’re spinning around the last thing you want is to have something come out of place! And when you hit the water you don’t want things flapping about, because it would hurt.” However, if you Google “Tom Daley” and “Speedos,” once you have finished marveling at his inguinal creases, you’ll appreciate why Out magazine once described the Speedo as “the single most perfect and pithy item of clothing ever designed for the male body.”

GAY GARB?

The exalted status of the Speedo in gay iconography goes some way to explaining why it is viewed with such fear and loathing elsewhere. In 2018, a brief-wearer named Chris Donohoe complained that he was the victim of homophobia after being thrown out of a pool party at a hotel in Las Vegas for flouting the “no Speedo” rule.

“It so obviously targets LGBTQ+ and non-gender-conforming people,” he argued. “They need to stop policing people based on their gender identity and sexuality.”

The hotel responded that the briefs went against their dress code.

Whatever your instinctive feelings towards the Speedo, you can tell that it is a design classic because the brand has become synonymous with the product — like “hoover” for vacuum cleaner. Other brands are, of course, available — and Speedo the company sells the full range of aquatic attire — but when someone says “Speedos” what comes to mind is, well, budgie smugglers. Tom Daley, incidentally, wears Adidas trunks.

Speedo the company began life as MacRae and Company Hosiery, founded by Alexander MacRae, a Scottish emigrant to Australia, in 1910. Speedo pioneered the “racerback” open-shoulder swimming costume for women in 1932 and introduced the nylon swimsuit at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, helping Australia’s swim team to eight out of 13 available gold medals. The swim brief itself was drawn up in 1960 by Peter Travis , who had arrived as a designer at the company the year before, tasked with designing leisurewear.

The first Speedos came in 17.5cm, 12.5cm and 7.5cm widths. “It was designed quite practically, not with fashion in mind,” he later recalled. “I realized you shouldn’t have anything around your waist that would twist when you swim. The only way you could stop that would be to end the cut on your hips. It’s designed as a purely functional object.”

The Speedo pioneers who Laidlaw had arrested in 1961 were let off without charge, by the way. Since no pubic hair was on show, the magistrate ruled that nothing indecent had been exposed. The publicity did the company no harm. Beach rules were relaxed in 1962 and in the first year the 17.5cm was the best seller, quickly overtaken in popularity by the 7.5cm.

The American swimmer Mark Spitz won seven golds in his Speedos at the 1972 Munich Olympics. Until swimsuits became hi-tech in the 1990s, the swim brief was the choice of swimmers, divers and water polo players.

And by the 1980s, the basic British man wore them, too.

Luke Day’s parents moved to Australia when he was six, and as soon as school finished each day, he was in his Speedos in the pool.

“My dad was always a Speedo man. Everyone around was. It wasn’t even a thing,” he recalls. “But then when I was in my teens, I would wear them outside Australia and people would go: ‘Woah! You’re wearing Speedos?’ Americans are horrified by them. I didn’t get it at all. Isn’t that what everyone wears?”

It’s certainly what I wore to my swimming lessons in the 1980s. But my 1990s teenagehood coincided with a change in trends that was a blessed relief. Puberty + swimming pools + extremely tight trunks was a combination I could do without. Long swimming shorts — Bermudas — appeared (around the same time as The Simpsons, Cherry 7-Up and Global Hypercolour T-shirts). Then, almost overnight, it became unthinkable to swim in anything except long shorts. By the mid-aughts, the Speedo was only marginally less out there than the mankini.

Nonetheless, the swimming brief has always had its strongholds — in Australia, as well as in Italy, Greece and France, where many an English teenager has been dismayed to discover that tight swimming trunks are compulsory in public swimming pools. The logic is that it is unhygienic to swim in shorts that may have been used to play football in, sit on the grass in, barbecue in and so on. I’d guess that a handful of Brexit votes were swung by this rule alone.

CONVERTS SPEAK

But if you consider the Speedo as solely a swimming garment, it becomes a little more thinkable to sport a pair. Andrew Barker, head of content at C Magazine, which covers style and culture in California, says he became a convert after a trip to Brazil five years ago.

“I always found them a bit ridiculous, somewhat dated and a little too revealing. But in Brazil everyone wears them — whether drinking a caipirinha, playing volleyball or carrying a surfboard. Young or old, gay or straight, the sunga is a staple. I came home with two pairs — one red, one green,” Barker says.

Barker now wears them on holiday in Europe, but never in Los Angeles, where he resides. The surf culture plus that peculiarly adolescent strain of American puritanism dictates that men wear shorts.

It is quite strange that most male swimmers opt for heavy, draggy swimwear; that we made a civilizational leap towards liberated mermanhood only to lose our collective nerve. It would be a bit like women collectively deciding that no, bikinis are a bit much, best go back to woollen bathing dresses.

“We can’t deny that they’re a huge gay thing,” says Day when I ask him if only a certain type of man can pull off a Speedo. “If you go to Mykonos or Ibiza, you will see hundreds of gay men wearing Speedos. It’s part of that 70s aesthetic. Think of Yves Saint Laurent or Burt Reynolds. But it’s a statement, too. There was a picture of David Beckham on a yacht wearing a white Speedo. A white one is quite an unapologetic zero-fucks-given type thing to wear. It’s bold. It’s confident.” It’s not to be attempted lightly.

But he holds some hope that the Speedo is becoming more acceptable, especially given the attention that even young British men give to honing their bodies.

“That iconic Daniel Craig coming out of the water moment wasn’t quite a Speedo but it was a tight number. I think that helped change things.”

What advice would Day have for the male who is thinking about going back to Speedos? “I’m not saying people should be hairless, but men should at least be aware of manscaping if they are thinking of going Speedo,” he says. “It’s about fit and cut. You need the right size for you. I quite like a retro, slightly loose, higher-waist Speedo.”

And perhaps we should stop being so judgmental. Peter Travis — who went on to design the interior of the Australian parliament building — expressed regret that his creation should have become a source of ridicule.

“I’ve heard people saying things like, ‘Oh that fat old man looks terrible in Speedos,’ and I don’t like that,” he once told an Australian paper. “The point is, he looks just as bad in anything, but he shouldn’t be criticized because he wants to wear something to swim in. He’s not there for people to look at. Why shouldn’t a person who wants to swim not be criticized?”

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

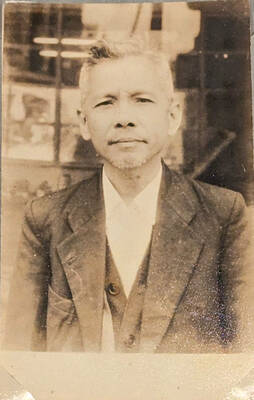

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only