June 8 to june 14

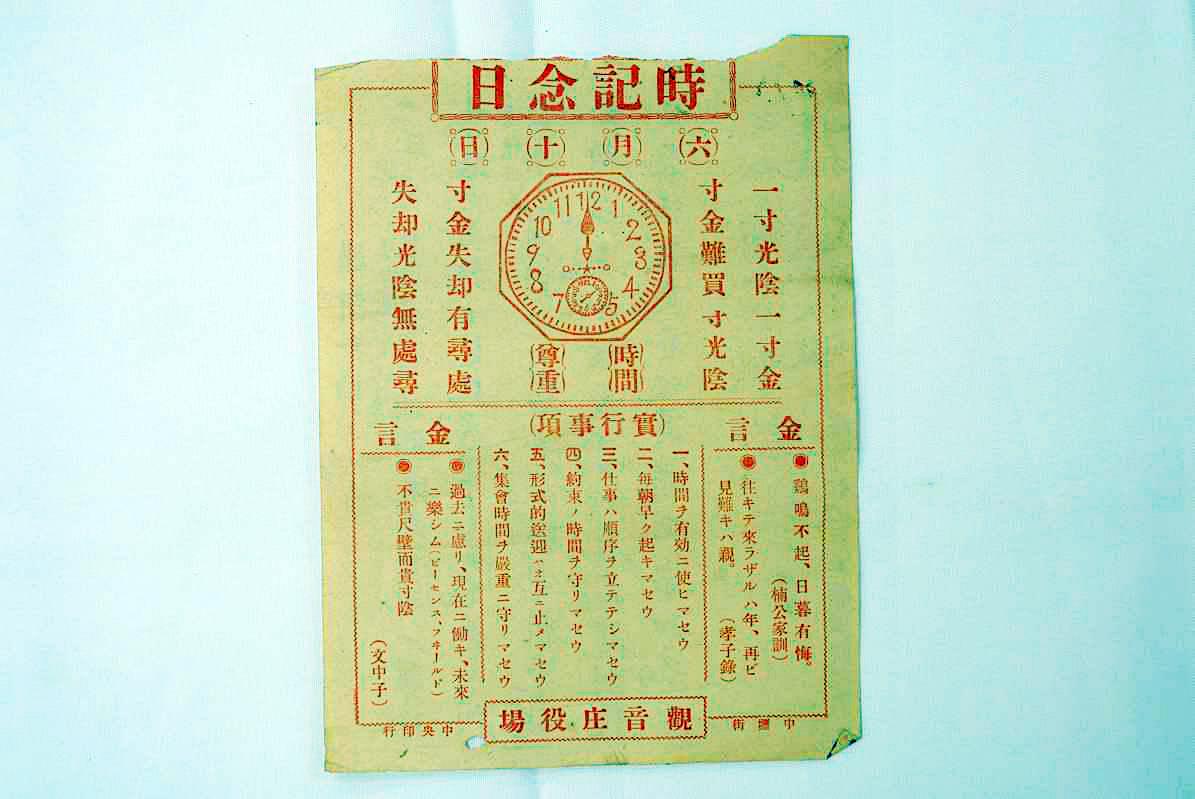

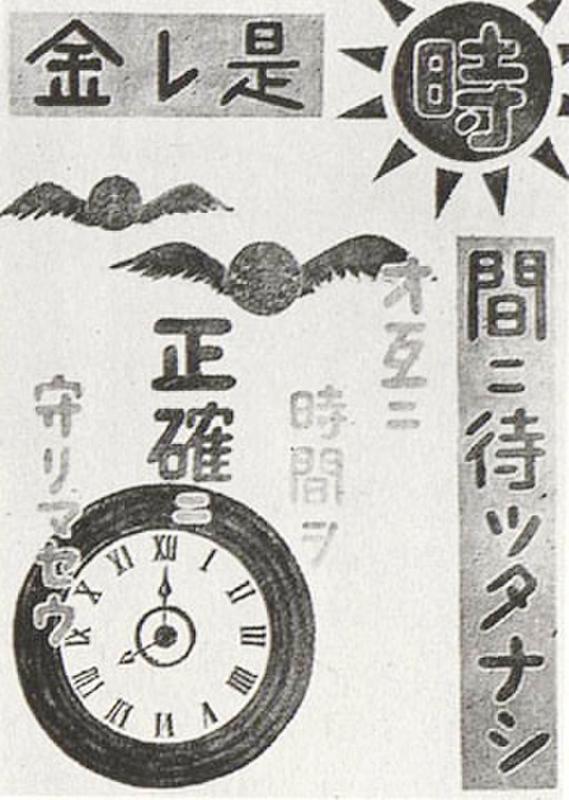

Every June 10 starting from 1921, students across Taiwan formed marching bands and paraded the streets, handing out flyers that reminded people to be punctual and adhere to the standard time. It was “Time Memorial Day” (時的紀念日), where schools and civic groups put on all sorts of activities to promote the habit.

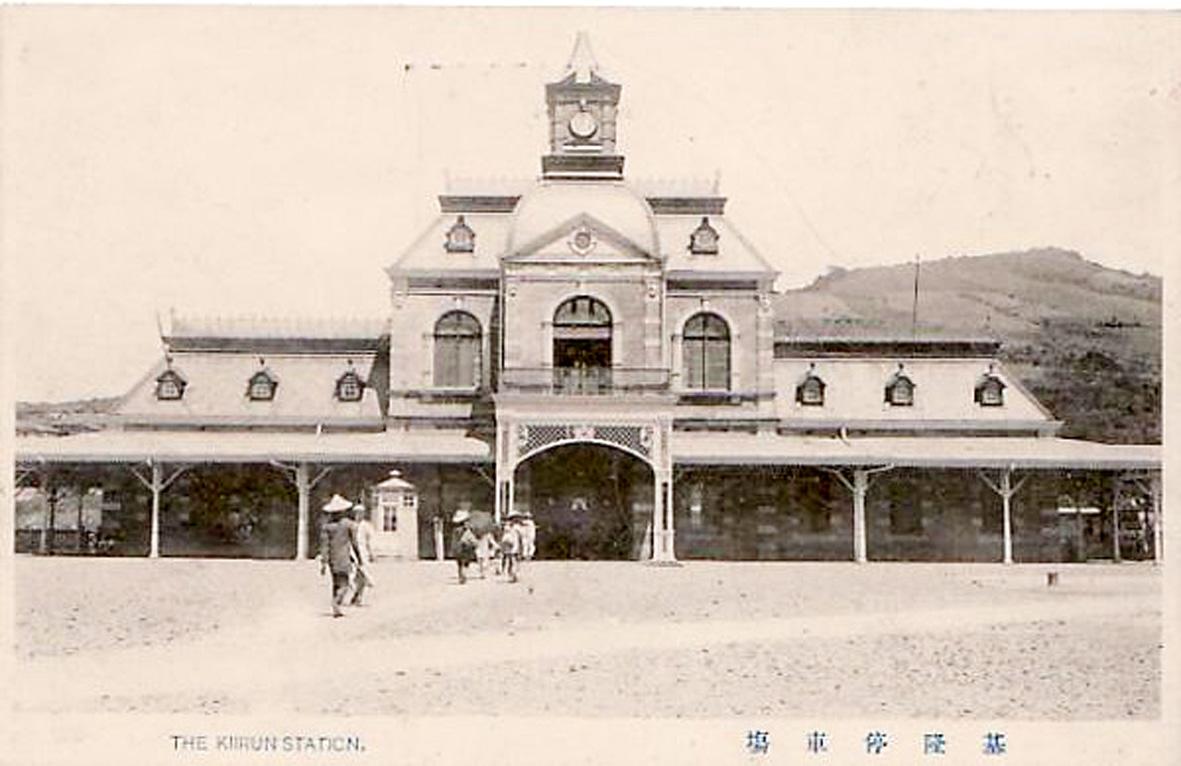

A mostly agrarian society when the Japanese arrived, there was little need for the average Taiwanese to know exactly what time it was. They followed the traditional Chinese system of dividing the day into 12 periods, and organized their lives around the lunar calendar and the 24 solar terms. Even after the colonizers implemented Greenwich Mean Time in Taiwan on Jan. 1, 1896, few people followed it unless they had government business, attended school or had a train to catch.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

An undated Time Memorial Day flyer features several Chinese proverbs about the importance of time and includes the following instructions: “1. Use time wisely. 2. Wake up early. 3. Establish routines for your tasks. 4. Be on time for appointments. 5. Refrain from excessive greetings and send-offs. 6. Take assembly times seriously.”

The Japanese took punctuality so seriously that it was among their first priorities when they captured Taipei on June 7, 1895. On June 27, with local resistance still raging across Taiwan, they began firing a daily “noon cannon” (午炮) at 11:30am from the walled city’s west gate. The practice spread to other cities over the years. In 1913, the citizens of Tainan set up a “noon-cannon collective” where businesses shared the gunpowder and labor costs.

In addition to Time Memorial Day activities, the introduction of radio to Taiwan in 1925 and the rise of factory work also contributed to the sense of time among the people. Finally, all citizens became subject to standard time when the Japanese launched its Kominka Movement (皇民化運動), a policy that sought to assimilate Taiwanese through strict social control.

Photo: Digital Archives

BEGINNING OF TIME

Before outsiders arrived, Taiwan’s Aborigines told time by observing celestial bodies and animal behavior. The Dutch introduced the hourglass in the 1600s, while Han Chinese settlers brought water clocks and incense sticks.

According to Whistle From the Sugarcane Factory (水螺響起) by Lu Shao-li (呂紹理), incense sticks remained the most common way to measure time in the 19th century. There was no standardized system, as being off by 15 or 30 minutes had little impact on one’s daily life in a farming village. The need for standardized time arose with the opening of Tamsui and Kaohsiung to foreign trade in 1860; the Gregorian “week” was first used in these two ports.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The first recorded mechanical clock arrived in 1878, but Lu writes that it was more of a status symbol than a practical tool. The Qing Empire made Taiwan a province in 1885 and established postal, telegram and railroad systems. While these institutions ran on standard time, they had minimal impact on ordinary people’s lives.

Japan adopted Greenwich Mean Time in 1888, and brought it to Taiwan in 1896. The colonial government established daily office hours from 8am to 4pm, with a two-hour lunch break and half-day off on Sundays. In November 1895, public servants were given Sundays and holidays off. This, in addition to students having weekends off, introduced the idea of the seven-day week.

In 1915, the government announced that it would be conducting a colony-wide census at exactly midnight on Oct. 1, prompting people to rush home before then.

“These people had unknowingly entered an entirely new world of time,” Lu writes. “Up to this point, unless they had official business, there was still little need to know the exact time.”

TIME TAKES ROOT

For most people, the main indicator of time was the police, who regularly patrolled the streets of every settlement. Writer and activist Yeh Jung-chung (葉榮鐘) recalls that since the neighborhood sanitation cop took the same route at the same time every day, people knew exactly when to clean their streets.

“Time Memorial Day” was first established in 1920 in Japan. The colonial government implemented it in Taiwan the following year, observing it until 1941.

The percentage of children entering the formal school system grew from 25 percent to 71.3 percent between 1920 and 1943, where they followed a tight hourly schedule. Although many reverted to old habits once they left school, they were at least used to the system.

The government also used train and car horns, and at one point even regular blackouts to remind people of the time. Sugarcane plantation workers arrived to work every morning at the sound of the steam whistle, hence the name of Lu’s book.

Punctuality was stressed at temple festivals as well. A news report notes that even though organizers of a 1925 Matsu procession insisted that participants follow a strict schedule, they still departed 45 minutes late.

The concept of time became pertinent to every citizen after the colonial government launched the Kominka Movement (皇民化運動) in the 1930s to shift Taiwanese culture closer to that of Japan. As World War II heated up, the government tightened its control over people’s lives, mobilizing them into various groups and collectives to rally their patriotism and support the war effort.

The colonial government made one final request for punctuality before their rule ended. On Aug. 14, 1945, the governor-general’s office persistently urged its subjects to tune in to the radio at exactly noon the next day.

Those who tuned in heard the voice of Japanese emperor Hirohito, who announced Japan’s surrender and the end of colonial rule.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them