April 6 to April 12

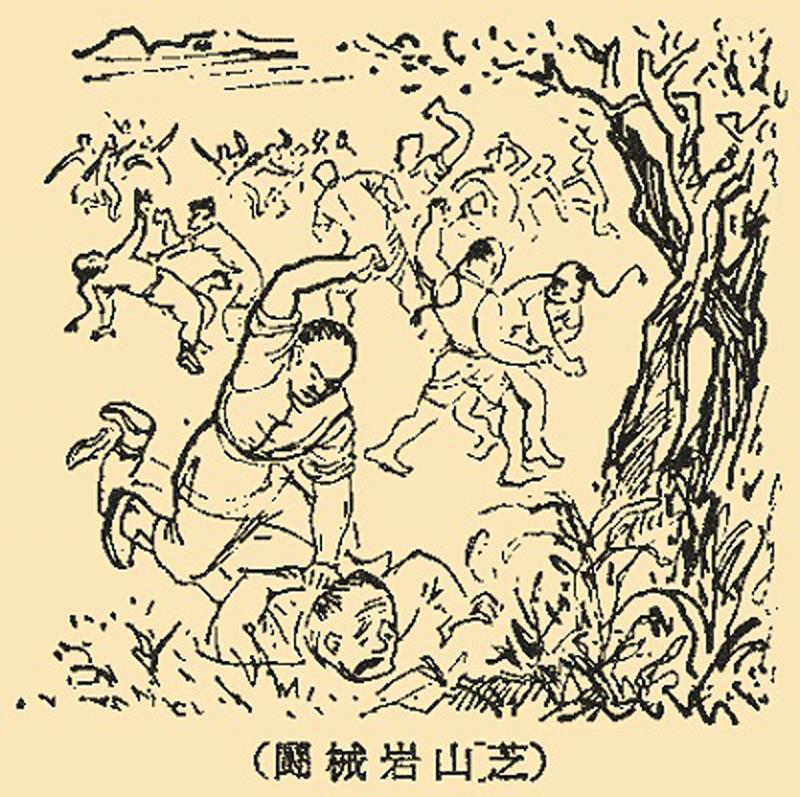

Han Chinese settlers from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou were such fierce rivals that simple activities such as buying supplies for festivals would often result in armed violence. It’s said that this was especially severe just before Tomb Sweeping Festival, and to prevent bloodshed Qing Dynasty officials ordered them to conduct their rituals on different days.

This is not unlike the government urging people to visit their ancestors’ graves on days other than yesterday’s official Tomb Sweeping Day, also known as the Qingming Festival, to curb the spreading of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) established National Tomb Sweeping Day while it still ruled China and carried it over to Taiwan, the idea of the entire nation sweeping tombs on the same day only became a reality when it was declared a public holiday in 1972.

Photo Courtesy of Yang Ying-feng

In 1975, when former KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) died on April 5, the government saw it as an opportunity for propaganda and fixed the anniversary of his death to tomb-sweeping day. Since the practice adheres to the solar calendar and could fall on April 4, 5 or 6, the anniversary of Chiang’s death was not always observed on the day he died.

Today, it is usually combined with Children’s Day to make a long weekend, which is another holiday that the KMT established when it was in China and carried over to Taiwan.

EARLY SOCIAL DISTANCING

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

One of the earlier mentions of tomb-sweeping activities in Taiwan can be found in a Chinese report published in 1799, which showed that the settlers closely adhered to the traditions of their homeland.

According to the Ministry of Culture’s Taiwan Encyclopedia, settlers from Zhangzhou in Fujian Province would sweep their ancestor’s tombs on the third day of the third lunar month, which this year fell on March 26. The ones from Quanzhou, also in Fujian Province, did theirs on the start of Qingming, which is equivalent to today’s Tomb Sweeping Day. This practice was noted in Lien Heng’s (連橫) General History of Taiwan (台灣通史), which was completed in 1918.

Hostilities between Zhangzhou and Quanzhou settlers were often escalated as they fought over supplies — usually meat — for tomb-sweeping rituals. According to Taiwan Encyclopedia, some accounts say that they hated each other so much that they refused to conduct the same ritual on the same day, while others say that the government mandated that they do it separately.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Hakka people were more flexible as they could conduct their rituals any time between the 15th day of the first lunar month and the Qingming Festival. Many Hakkas still follow this today.

The practice of tomb-sweeping continued under Japanese rule — at least in the early days, as there is scant information on the topic. In Ishu Momiyama’s 1903 Chinese-language poems of life in Taiwan, he criticized the practice of burning spirit money in front of graves during Qingming as wasteful.

In the Republic of China’s early days, the government designated Qingming as Arbor Day since its founder Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) was a proponent of afforestation. After Sun died on March 12, 1925, the government moved Arbor Day to his death anniversary, which is still observed in Taiwan today. It wasn’t until 1935 that the government declared Qingming as “National Tomb Sweeping Day” and held an official ceremony on April 6 at the tomb of the Yellow Emperor, the legendary progenitor of all Han Chinese.

QINGMING GETS POLITICAL

After World War II, a group of Taiwan’s elite and intellectuals headed to China to meet with the KMT and to commemorate the liberation of Taiwan from Japanese rule. One of their objectives was to worship at the Yellow Emperor’s grave. However, because it was dangerously close to the Chinese Communist Party’s base in Yanan, they conducted the ritual from a distance at a nearby city.

In 1950, the same group petitioned the government to designate a day where the nation would worship the Yellow Emperor’s tomb. On April 5, 1951, the first such ceremony was performed in Taiwan at the National Martyr’s Shrine. It would take place every year until it was canceled in 2017.

“Since China has fallen, we can only worship our progenitor from a distance … We must solemnly swear before our ancestors and predecessors that we will surely reclaim our homeland and save our compatriots,” a 1953 propaganda brochure lamented.

Tomb Sweeping Day became a national holiday in 1972. It was part of the government’s Chinese Cultural Renaissance Movement, which was launched in 1967 as an antidote to the Cultural Revolution in China, which sought to destroy all things traditional.

Chou Chun-yu (周俊宇) writes in Recreating Tomb Sweeping Day under Chinese Nationalist Party Rule (中國國民黨政權下的清明節再製) writes that the goal was to encourage people to conduct their tomb sweeping activities on a unified day by giving them the day off. Even Aborigines, who had their own traditions, began participating during this time.

Three years later, Chiang died on April 5. On July 15, then-president Yen Chia-kan (嚴家淦) declared that every Tomb Sweeping Day would also be observed as the anniversary of Chiang’s death. This would strengthen Chiang’s image as the savior of the nation as it put him in league with the Yellow Emperor, Chou writes.

Since Tomb Sweeping Day fell on April 4 the following year, the anniversary of Chiang’s death was observed a day earlier. The state-run Central Daily News (中央日報) quoted a ceremony attendee as saying, “We will return every year, because only under the leadership of [Chiang] has Taiwan become a safe and prosperous anti-communist base, and only because of this do we have the luxury of sweeping our ancestor’s graves.”

Since Tomb Sweeping Day fell on April 5 every year between 1975 and 2007, besides leap years, many think that Tomb Sweeping Day was tied to Chiang’s death. But according to Central Daily News reports, it was the other way around. Old articles show that the anniversary of Chiang’s death was indeed observed on April 4 during leap years — except in 1988, for unknown reasons.

The anniversaries for Chiang’s birth and death were abolished as national holidays in 2007.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only