Earlier this month, the Ministry of Economic Affairs announced that domestic dairy production hit a historic high of 6.6 million tonnes last year. Local demand continues to outstrip supply. That seems counterintuitive, considering that dairy is largely absent from traditional Chinese food and drink, and worldwide, lactose intolerance is most prevalent among people of East Asian descent.

Yet after moving here a year ago, it surprised me to discover that Taiwan resembled a Biblical land of fresh milk (and honey). Back home in Singapore, the island boasted a solitary cow farm (and one goat farm). Almost all the milk I drank growing up — along with more than 90 percent of food overall — was imported. There was usually little transparency around the sources of fresh milk, which always tasted a bit off to me.

Contrast that with Taiwan, populated with 132,995 heads of dairy cattle as of the end of last year. Supermarkets offer a tyranny of choice, so one trick I’ve learned is to look out for a black-and-white cow sticker on the carton, which displays information about the season of production and volume of milk in a compact manner. Introduced by the Council of Agriculture in 1986 to address food safety concerns, the sticker indicates that the milk has been inspected and certified to be fresh milk with no additives.

Photo: Davina Tham, Taipei Times

Aside from comparing a number of well-known milk brands against each other, I wanted to understand how Taiwan has come to produce milk of such quality, and how the beverage became a part of local diets. The answer to that constitutes one of the country’s most successful projects of economic modernization, but also reveals decades of colonial influence and cultural aspirations.

EARLY HISTORY OF MILK

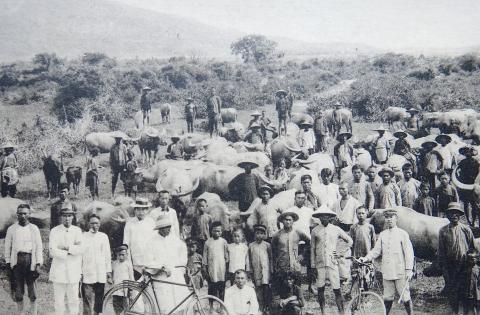

The native water buffalo was only occasionally milked by locals. This yielded small quantities that were sometimes sold fresh to missionaries or used to make small, round soft cheeses, according to animal scientist Sung Yung-i (宋永義) writing in the Dairy Farming Newsletter (酪農天地).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Before the Japanese colonial era, the earliest cattle kept for dairy purposes were meant to service Western communities. In 1872, some cattle were even kept at Oluanpi Lighthouse (鵝鑾鼻燈塔) in Pingtung to produce milk for European officers stationed there, cultural historian Chen Yu-chen (陳玉箴) writes in the National Taiwan Library’s Newsletter on Taiwan Studies (臺灣學通訊).

It took a colonial endeavor for the first dairy farm of scale to open in Taiwan. With the Westernization of diets during the Meiji Restoration, the Japanese had developed a taste for milk and beef. Chung Dairy Ranch (柊牧場) opened in 1896 to provide milk for Japanese servicemen, particularly the wounded who needed extra nutrition.

The ranch only took off after a breakthrough in cross-breeding temperate and tropical breeds of dairy cattle, which could acclimatize to the local heat and humidity. This was such a source of pride for the Japanese colonizers that when the head of an important imperial family branch visited in 1908, the government made a point of presenting him with fresh “imperial-grade” milk (御乳) made in Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chen writes that the colonial period cemented the image of milk as a prestige product in the eyes of locals, despite (or perhaps because of) its consumption being limited to Western and Japanese communities. This connection made dairy farming a vital part of Taiwan’s post-war economic reconstruction.

To improve nutrition and raise the value and status of the farming industry after the Chinese Civil War, the Sino-American Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction allocated land and provided assistance to set up 20 dairy ranches in Taoyuan, putting low-quality agrarian land to use as pasture. Since then, milk has been a constant in the local agricultural sector.

MODERN OFFERINGS

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Curious about the range of local milks on offer, I conducted a blind taste test of nine varieties, focusing on brands that can be found at the nation’s three largest supermarket chains — Wellcome, Simple Mart and Pxmart — and convenience stores. All are fresh whole milks with no additives. Here they are, ranked from worst to best:

Wei Chuan Foods (味全食品) is one of the oldest distributors of milk in Taiwan, starting from the 1950s, but its reputation took a hit when it was embroiled in a food safety scandal in 2014. Nonetheless, its Lin Feng Yin (林鳳營, NT$89 for 936ml) brand remains widely stocked and is a household name. This milk had the strongest fragrance but tasted relatively diluted and flavorless, leaving a slightly greasy mouthfeel.

Chu Lu Ranch (初鹿牧場, NT$94 for 946ml) is no mere dairy farm but a bona fide tourist attraction, attracting more than 260,000 visitors last year. I had high hopes, given the ranch’s imagery of rolling green pastures. Although the unique qualities of its milk had not been apparent to me before, Chu Lu stood out in this test. Its aroma and flavor were the most evocative of a barnyard animal, with an almost gassy, methane-like scent in the carton. Upon tasting, the barnyard taste remained overpowering and lacked sweetness.

I’ve only seen KenKen Bread (肯啃鮮乳) at Pxmart, where its single-farm milk is a must-buy whenever I manage to spot it on the shelves. Unfortunately, that range proved elusive this time. Instead, KenKen Bread’s blended variety (NT$84 for 936ml) was disappointing, tasting watery and lacking in fragrance. Ru Xiang Shi Jia (乳香世家, NT$88 for 936ml) tasted similarly thin, with little natural sweetness.

Dr. Milker earned image points for coming in a glass bottle (250ml for NT$40). In a blind taste test, it was almost indistinguishable from Rui Sui (瑞穗, NT$92 for 930ml). Both are middle-of-the-road specimens of the basic qualities I expect from milk — moderately sweet, fragrant and creamy, certainly not out of place in a bowl of cereal.

Lun Bei (崙背, NT$88 for 936ml) has only been in stores since May, and represents a growing effort by dairy farmers to create a regional brand identity. Created by the dairy farmers of Lun Bei Township in Yunlin County, in cooperation with the county government, this milk had a particular maltiness to it, and is a welcome alternative to the usual mass-market brands.

I did not have high expectations for Guang Quan (光泉, NT$90 for 936ml), a mass-market blended fresh milk that is commonly used in cafes and tea shops. Tasted blind, however, it performed surprisingly well, ranking second with a sweet, almost flowery aroma and pleasant flavor and aftertaste.

Ultimately, it was Liu Jia Village (六甲田莊) that emerged tops, just edging out Guang Quan by being a touch creamier. Produced by Taiwan Dairy Farm (台灣牧場), a cooperative of dairy farmers from Tainan formed in 2004, this milk is an all-rounder, boasting a strong milky fragrance, pronounced sweetness and a full-bodied mouthfeel. And at NT$79 for 946ml, it also manages to be the cheapest of this selection.

The only drawback is that for now, Liu Jia Village is available exclusively at Pxmart. In a kitchen emergency, the ubiquitous Guang Quan, which can be found at any corner convenience store, should more than meet a variety of uses. I’ll be adding both to my grocery list from now on.

Sept. 1 to Sept. 7 In 1899, Kozaburo Hirai became the first documented Japanese to wed a Taiwanese under colonial rule. The soldier was partly motivated by the government’s policy of assimilating the Taiwanese population through intermarriage. While his friends and family disapproved and even mocked him, the marriage endured. By 1930, when his story appeared in Tales of Virtuous Deeds in Taiwan, Hirai had settled in his wife’s rural Changhua hometown, farming the land and integrating into local society. Similarly, Aiko Fujii, who married into the prominent Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家) in 1927, quickly learned Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) and

The low voter turnout for the referendum on Aug. 23 shows that many Taiwanese are apathetic about nuclear energy, but there are long-term energy stakes involved that the public needs to grasp Taiwan faces an energy trilemma: soaring AI-driven demand, pressure to cut carbon and reliance on fragile fuel imports. But the nuclear referendum on Aug. 23 showed how little this registered with voters, many of whom neither see the long game nor grasp the stakes. Volunteer referendum worker Vivian Chen (陳薇安) put it bluntly: “I’ve seen many people asking what they’re voting for when they arrive to vote. They cast their vote without even doing any research.” Imagine Taiwanese voters invited to a poker table. The bet looked simple — yes or no — yet most never showed. More than two-thirds of those

In the run-up to the referendum on re-opening Pingtung County’s Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant last month, the media inundated us with explainers. A favorite factoid of the international media, endlessly recycled, was that Taiwan has no energy reserves for a blockade, thus necessitating re-opening the nuclear plants. As presented by the Chinese-language CommonWealth Magazine, it runs: “According to the US Department of Commerce International Trade Administration, 97.73 percent of Taiwan’s energy is imported, and estimates are that Taiwan has only 11 days of reserves available in the event of a blockade.” This factoid is not an outright lie — that

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) yesterday paraded its military hardware in an effort to impress its own population, intimidate its enemies and rewrite history. As always, this was paced by a blizzard of articles and commentaries in the media, a reminder that Beijing’s lies must be accompanied by a bodyguard of lies. A typical example is this piece by Zheng Wang (汪錚) of Seton Hall in the Diplomat. “In Taiwan, 2025 also marks 80 years since the island’s return to China at the end of the war — a historical milestone largely omitted in official commemorations.” The reason for its