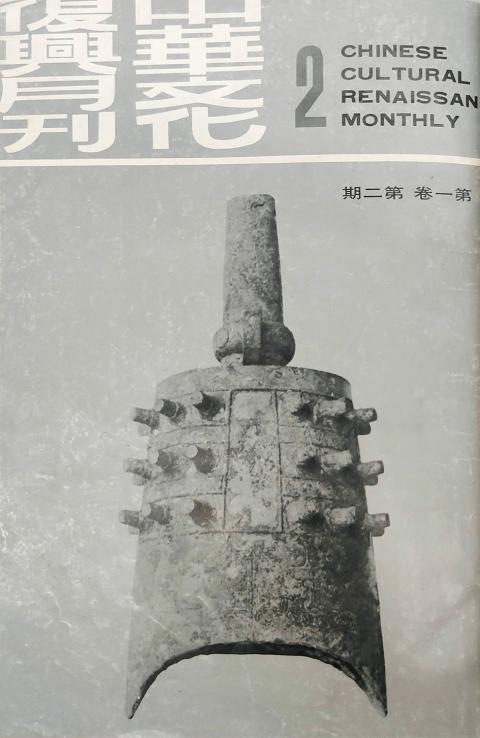

July 29 to Aug 4

While the Chinese were doing everything they could during the Cultural Revolution to destroy their cultural heritage, Taiwan launched the Chinese Cultural Renaissance Movement to do the opposite.

On the surface, the goal of the movement was to establish Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government as the rightful heir and protector of Chinese culture and morals, but as Lin Kuo-hsien (林果顯) shows in “Study of the Council on Promotion of the Chinese Cultural Renaissance Movement” (中華文化復興運動推行委員會之研究), it also had a political agenda.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

With reclaiming China pretty much out of the question, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) launched the movement as a “‘cultural counterattack’ [against China] to keep people’s spirits mobilized in order to continue its wartime provisions, and to build up the image of its leader as the successor of traditional Confucian morals to solidify the legitimacy of [KMT] rule,” he writes.

The council was established in late July 1967, with Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) presiding over 11 committees covering aspects of life including education, mass media, youth activities, women’s issues and public morals.

After many changes in structure and objectives, the council still exists today as the General Association of Chinese Culture (中華文化總會). Its mission today shows that like many organizations in Taiwan, it retains the word “Chinese” only in name: “To continue to enhance and cultivate Taiwan’s cultural power; to continue to facilitate cultural exchanges and cooperation between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait; and to strengthen exchanges between Taiwan and the international community.”

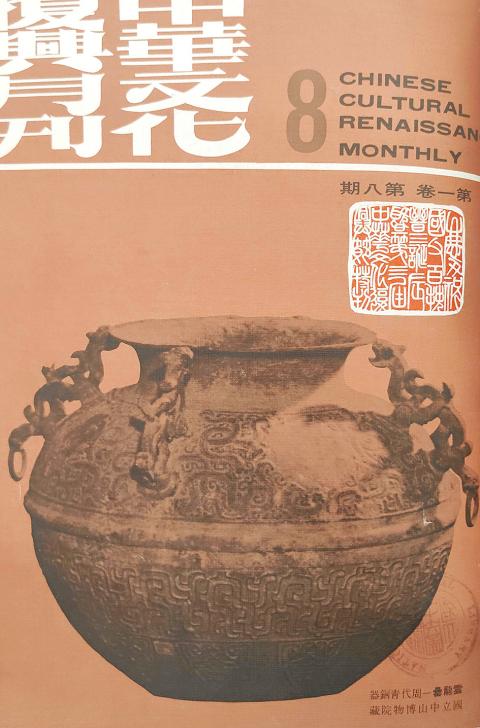

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

LEGITIMIZING AUTHORITARIANISM

Taiwan was a contradiction in the 1960s. It had obtained US support by championing free and democratic values and staunchly opposing communism — the “authoritarian and brutal” Chinese Communist Party. However, Taiwan remained under martial law, the ROC National Assembly had not held elections since 1947 and Chiang established himself as president-for-life under wartime provisions even though he had reached his term limit in 1960.

While the KMT had little hope of retaking China, it used propaganda to maintain the illusion that war could break out at anytime to justify its military rule and keep its population united and patriotic. The Cultural Revolution broke out in China in 1966, giving the KMT a perfect opportunity to launch the Chinese Cultural Renaissance Movement as a countermovement.

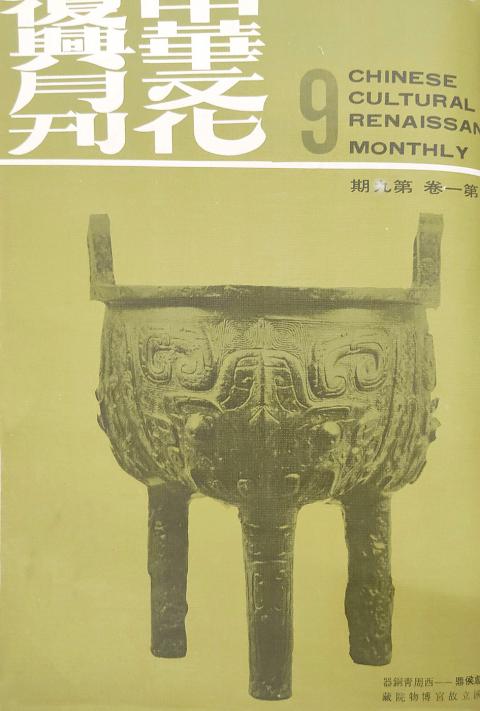

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

It was not the first not the first of its kind. The KMT had launched the Cultural Reform Movement (文化改造運動) and the Cultural Cleansing Movement (文化清潔運動) in the 1950s. These movements share the common goals of shaping the world view of its constituents by repeatedly promoting KMT founder Sun Yat-sen’s (孫逸仙) Three Principles of the People (三民主義), fostering unwavering allegiance to Chiang and carrying out the ultimate goal of defeating the Chinese communists.

The council was made up of scholars, cultural experts and a large number of high-level KMT officials. In addition to promoting traditional Chinese arts, it sought to instill the ancient “Four Principles and Eight Virtues” (四維八德) among the populace.

These ideals were heavily integrated into the school curriculum, and students participated in patriotic essay contests and singing competitions. Since many young Taiwanese had never lived in China, the association steered them toward identifying with China, which for ROC leaders included Taiwan. In this way, the students would view reclaiming “the motherland” as their own personal mission, Lin writes.

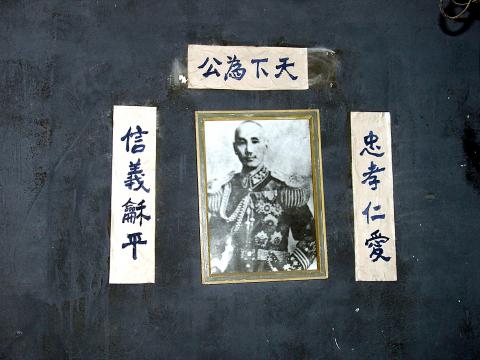

Photo courtesy of David Schroeter via Flickr

The council even claimed that Taiwan’s indigenous people came from China, and aimed to eradicate local languages in favor of Mandarin. It also established guidelines on how people should conduct themselves, ranging from respecting the flag and anthem to personal hygiene and manners such as refraining from eating while walking. It also focused on international propaganda at a time when the world’s powers started to question the KMT’s legitimacy in representing China.

POST-CHIANG YEARS

Chiang died in 1975, and his successor Yen Chia-kan (嚴家淦) took over as council head. The ROC’s standing in the world had changed dramatically — it had broken ties with the US and withdrawn from the UN while domestically it faced a proliferation of democracy protests and publications. Premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) was more focused on building the economy and political reform, and declined to take over as committee head when he became president in 1978, indicating that the movement’s importance had diminished.

“Chiang Kai-shek, who led both the party and the military and was also the protector of traditional morals, was irreplaceable,” Lin writes. Yen, who many saw as a lame duck president, actually remained as council head until 1990 despite not holding any political position after 1978.

The younger Chiang was less interested in promoting traditional morals, instead pushing a modern “cultural construction” (文化建設) program that would set up libraries, concert halls, museums and other institutions in every county and city. This also included setting up cultural festivals, awards and fostering talent. Chiang understood the importance of involving Taiwanese in government affairs, and his policies also paid attention to local folk culture and historic relics instead of being completely Chinese-oriented.

Nevertheless, the council continued to operate as it did before. One notable program it undertook in the early 1980s involved endorsing the plum blossom — the national flower, which blooms in cold weather — as a defining symbol of Chinese culture.

In 1991, the council was downsized and restructured as the General Association of Chinese Cultural Renaissance (中華文化復興運動總會) with then-president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) as head. While the mission was still to promote Chinese culture and build national character, Lin notes that the budget allocated to promoting Taiwanese culture was significantly larger than the one for Chinese culture.

Chiang Kai-shek would surely turn in his mausoleum upon hearing that!

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

The depressing numbers continue to pile up, like casualty lists after a lost battle. This week, after the government announced the 19th straight month of population decline, the Ministry of the Interior said that Taiwan is expected to lose 6.67 million workers in two waves of retirement over the next 15 years. According to the Ministry of Labor (MOL), Taiwan has a workforce of 11.6 million (as of July). The over-15 population was 20.244 million last year. EARLY RETIREMENT Early retirement is going to make these waves a tsunami. According to the Directorate General of Budget Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), the

Many will be surprised to discover that the electoral voting numbers in recent elections do not entirely line up with what the actual voting results show. Swing voters decide elections, but in recent elections, the results offer a different and surprisingly consistent message. And there is one overarching theme: a very democratic preference for balance. SOME CAVEATS Putting a number on the number of swing voters is surprisingly slippery. Because swing voters favor different parties depending on the type of election, it is hard to separate die-hard voters leaning towards one party or the other. Complicating matters is that some voters are

Last week the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) announced that the legislature would again amend the Act Governing the Allocation of Government Revenues and Expenditures (財政收支劃分法) to separate fiscal allocations for the three outlying counties of Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu from the 19 municipalities on Taiwan proper. The revisions to the act to redistribute the national tax revenues were passed in December last year. Prior to the new law, the central government received 75 percent of tax revenues, while the local governments took 25 percent. The revisions gave the central government 60 percent, and boosted the local government share to 40 percent,

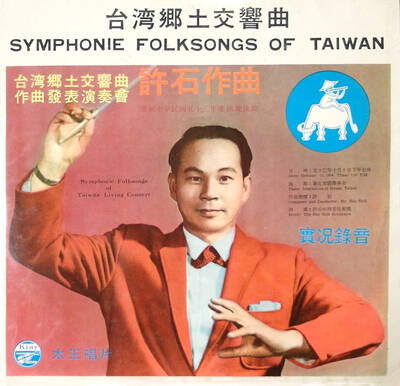

Sept 22 to Sept 28 Hsu Hsih (許石) never forgot the international student gathering he attended in Japan, where participants were asked to sing a folk song from their homeland. When it came to the Taiwanese students, they looked at each other, unable to recall a single tune. Taiwan doesn’t have folk songs, they said. Their classmates were incredulous: “How can that be? How can a place have no folk songs?” The experience deeply embarrassed Hsu, who was studying music. After returning to Taiwan in 1946, he set out to collect the island’s forgotten tunes, from Hoklo (Taiwanese) epics to operatic