It all started in 2016 with a bronze statue commemorating the tragic day in November 1963 when a giant octopus upended the Staten Island ferry, killing nearly 400 people in New York.

Wait, what — a giant octopus? Artist Joseph Reginella smiles. Yes, you read that right.

Last year, another statue appeared in Battery Park, at the lower tip of Manhattan — a monument to the Wall Street bankers trampled to death in October 1929 when circus impresario P.T. Barnum’s elephants broke into a panicked stampede while crossing the Brooklyn Bridge. Hard to believe? Well, quite. A few months ago, strollers along the water’s edge in New York found a new statue dedicated to the six crew members of a tugboat who were abducted by aliens in July 1977.

Photo: AFP

The three memorials to three made-up tragedies sprung from the vivid imagination of Reginella, a 47-year-old sculptor and jokester who has made an art out of monuments commemorating non-existent victims.

Reginella — who makes his living building models and props for movies, amusement parks and department stores — realizes it’s rather a peculiar hobby. He makes the bronze sculptures in his spare time, in the basement of his Staten Island home.

His 2016 sculpture of the octopus sinking the ferry was such a popular hit that he decided to produce a new monument each year along the same lines — and following the same sophisticated sense of humor.

Photo: AFP

DOCUMENTS LEND CREDIBILITY

Reginella begins by choosing the date of the invented disaster with care — and having it coincide with a real tragedy.

The ferry “sank” on Nov. 22, 1963, the day president John F. Kennedy was assassinated. The elephant stampede took place on Oct. 29, 1929, the day of the massive Wall Street crash. The tugboat crew “vanished” on the night of July 13, 1977, when a huge blackout plunged New York into darkness.

Photo: AFP

The idea is that the enormity of the real events will make people think — maybe — that they somehow missed the other tragedy that he invented.

“That was my vehicle to kind of try to have people believe this,” he said. “And then I took the template — I had such great success with this, it really went crazy — that I continued the tradition.”

Each statue comes with a plaque explaining the event in earnest tones, designed to lend a whiff of authenticity.

The elephant stampede, for example, is described as “one of the most horrific land mammal tragedies in our nation’s history.”

And at a moment in America when everyone goes to Google to verify or look up information, Reginella pushes the joke onto the Internet, conjuring up a panoply of fake documentation, including newspaper articles and online documentaries to bolster the illusion.

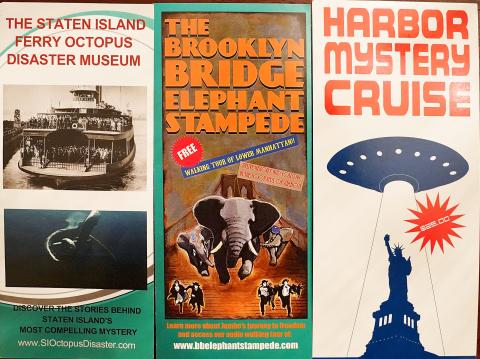

For his latest piece on the tugboat alien abduction, there is even a tourist brochure offering boat tours to the site where the sailors were allegedly kidnapped. A curious observer can type “octopus” and “Staten Island ferry” into YouTube and find a black-and-white documentary featuring archival footage of putative wreckage, along with witnesses and experts talking about the disaster.

Each event has its own Web site with souvenirs on sale, including real t-shirts priced at US$25 each and reproductions of the original model for US$100 a piece.

Several thousand fans of Reginella’s work, who share his quirky sense of humor, have bought a piece of his alternate history, allowing him to finance new projects, which generally take him six to nine months to complete, with the help of his wife and friends.

Despite their size, the statues are easy to assemble and move, and Reginella unveils them in Battery Park on weekends or in his spare time.

NOT ‘FAKE NEWS’

With such a high degree of sophistication, Reginella could pass for a pioneer of the “fake news” that has taken over social media in recent years.

But he rejects the term — a catch phrase closely associated with President Donald Trump and his attacks on the media.

“Mine is much more for fun, it’s not malicious,” he said. “I am more like the carnival barker, showing you the sideshow attraction.”

Despite his growing profile, Reginella remains rather humble about it all, and sees himself as a purveyor of inoffensive “hoaxes” for entertainment purposes.

The artist revels in the amused reactions of passers-by who stop to take selfies with his sculptures, some of whom wonder aloud if the events actually occurred.

Of course, despite the fantastical details of the alleged events, some people actually believe they are true. But usually, that belief is quickly dispelled. If someone persists in their belief, Reginella is the first to regret it.

“Some people just look at it and they’re just like, ‘Huh, who knew?’” he laughed. “And I’m like, ‘Are you kidding me?’” “It did not really anger me, but it really got me thinking. It was kind of a letdown.”

He admits there is “a flip side to it. It’s definitely to show people, ‘Don’t take things at face value, do your due diligence.’”

Reginella remained coy about his next project, and said he may even take a break next year from his usual production of one sculpture a year.

“I really don’t want to say because... it’s like a magician not wanting to reveal his secrets,” he says.

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

It was just before 6am on a sunny November morning and I could hardly contain my excitement as I arrived at the wharf where I would catch the boat to one of Penghu’s most difficult-to-access islands, a trip that had been on my list for nearly a decade. Little did I know, my dream would soon be crushed. Unsure about which boat was heading to Huayu (花嶼), I found someone who appeared to be a local and asked if this was the right place to wait. “Oh, the boat to Huayu’s been canceled today,” she told me. I couldn’t believe my ears. Surely,

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she