I had a free morning in Kaohsiung, so I decided to see a bit more of Hamasen (哈瑪星) in the southernmost part of the city’s Gushan District (鼓山區). This neighborhood is often bypassed by tourists eager to visit the nearby Former British Consulate.

The toponym Hamasen derives from the Japanese pronunciation of two Chinese characters meaning “coast railway” (濱線). When the Tainan-Kaohsiung railroad began operations in 1900, Kaohsiung’s principal station was located beside what’s now Gushan 1st Road (鼓山一路), 3.5km southwest of the current Kaohsiung Main Railway Station.

No trains have stopped at the old “coast railway” station, now part of Hamasen Railway Cultural Park (哈瑪星鐵道文化園區), for more than a decade. Inside the station building, you’ll find some quaint fixtures and fittings. Outside, vintage locomotives are on display near the original platforms. The rest of the park used to be a marshaling yard. Now thoroughly beautified, it attracts families who fly kites and picnic in the late afternoon sun.

Photo: Steven Crook

When I walked out of Exit 2 of Sihzihwan Metro Station (西子灣站) at the end of Kaohsiung’s Orange Line, I headed in the opposite direction, however, into the heart of what was once south Taiwan’s most prosperous commercial district. Businesses near the station rent out bicycles and e-scooters, but the distances aren’t great, and parts of Hamasen are inaccessible to two-wheelers.

HAMASEN’S ARCHITECTURE

My first target was the four-story Hamasen Trader Building (哈瑪星貿易商大樓; open 10am to 5pm Tuesday to Sunday; free admission), on the corner of Linhai 3rd Road (臨海三路) and Jiesing 2nd Street (捷興二街). Built in the 1930s as a 23-room hotel, this handsome concrete structure was used after World War II as temporary housing for soldiers arriving from China. After the final tenant went bankrupt in 2014, the authorities stepped in to prevent its demolition.

Photo: Steven Crook

The building was opened to the public in September. The lower three floors are given over to displays about the building and the neighborhood, and some of the photos are striking. The top floor, where books about Kaohsiung are sold, is a venue for seminars. There’s no ceiling, so visitors can see the timber framework that holds up the roof. The wood looks new because it is; every beam was replaced during a recent renovation.

Next, I walked to 18 Linhai 2nd Road. No sign or information board explains the history of the redbrick building there, but by searching online I discovered it was once Kaohsiung Police Bureau (高雄警察署). Completed sometime before 1920 as a local government office, detention cells and a fire station were added when it was converted into a police station. After World War II, it was sold off to a trading business, which explains why it isn’t open to the public.

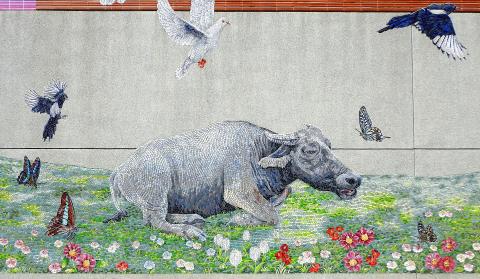

Further west on Linhai 2nd Road, at the intersection with Gubo Street (鼓波街), I stopped at the Memorial Park for Hotel All In One Historic Building (四海之家歷史建築紀念公園; open 24 hours). This marks the spot where Hotel All in One (四海之家), a hostel for sailors and fishermen, stood between the 1940s and 2005. The building, which preservationists tried to save, was bulldozed so an elementary school could be expanded. By far the most interesting feature of the park are two colorful mosaics. One depicts the hotel’s demolition; the other shows a water buffalo surrounded by birds and butterflies.

Photo: Steven Crook

Heading north along Gubo Street brought me to Dengshan Street (登山街, “climb the mountain street”). South of Dengshan Street, the ground is flat; north of this thoroughfare, the topography becomes steep.

Rather than head right to the 1920s-built Kaohsiung Red Cross Nursery (紅十字育幼中心) at number 28, I turned left to what is perhaps the most beautiful single building this side of the Love River. The fully-restored Wude Martial Arts Center (武德殿振武館) turned 94 this year. It’s probably the oldest of the dozen or so colonial-era butokuden halls that survive in Taiwan.

Arriving at the center (36 Dengshan Street; open 10am to 6pm Tuesday to Sunday; free admission) just before lunchtime on a weekday, I found the place utterly deserted. There were no other tourists — and not even a volunteer keeping an eye on the place. That surely says something positive about public safety and the lack of vandalism in Taiwan.

Photo: Steven Crook

The center’s exterior bears vertical arrow motifs that symbolize the samurai ethos. The banyan tree in front of the center is one of several places in Taiwan where the Japanese custom of leaving behind ema (wooden plaques not much larger than credit cards on which visitors write prayers or wishes) has caught on in recent years.

HISTORICAL SITE

This wasn’t my first visit to Wude Martial Arts Center, yet previously I’d never noticed the steps up the hill behind it. They provide access to a few tiny and unkempt houses. This part of Kaohsiung has several similar clusters of hillside hovels. If Japanese-influenced mercantile elegance is one face of Hamasen, post-war slums are another.

Photo: Steven Crook

A minute later I found myself on Cianguang Road (千光路). Walking west, I soon reached the campus of National Sun Yat-sen University (中山大學), and the new Lane 60 Dengshan Street Historical Site (登山街60巷歷史場).

According to on-site Chinese and English-language information panels this corner of Hamasen was occupied by Chinese refugees in 1954. To ensure a regular water supply, they diverted a creek. Some of the old houses here have been cleared away; several are still occupied. Not one, unfortunately, is open to the public. Many visitors would be interested to see the conditions in which people lived half a century ago.

In addition to creating a wide path through the neighborhood, the authorities have added two eye-catching structures. One is a Japanese-style public bathroom made partly of wood. It’s as large as — and looks more luxurious than — many of the homes hereabouts.

Photo: Steven Crook

Rather than build a skywalk, Kaohsiung City Government has constructed what they call the Time Tunnel Slide (時空廊道滑梯). On it, visitors sit on thick rectangular boards and zip down the hill at a speed that’s fast enough to make the experience exhilarating, yet slow enough to enjoy the view. The slide is 79m long with an average gradient of 18 degrees. The ride down takes around 30 seconds.

I prefer this slide to a skywalk for another reason. The structure is almost entirely steel, rather than concrete; if the authorities decide one day to scrap it, recycling the material will be far easier. If you want to try the slide, call 0911-728-000. Scheduling and booking arrangements are quite complicated; the charge per person is NT$50/100.

As I made my way down the hill, I checked if the tombstone of William Hopkins was still in place. Hopkins was an Ulsterman who drowned near here in 1880, and his grave marker is all that’s left of a 19th-century foreigners’ cemetery that held the remains of around 34 individuals.

The graveyard disappeared piece by piece as squatters took over the land, but Hopkins’ tombstone is still here, right beside a small single-story concrete house (30-7, Lane 60, Dengshan Street). It’s a little hard to spot because the homeowner dries clothes and stores items in front of it. No one seems to object, however, if you get up close to take photos.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture, and business in Taiwan since 1996. Having recently co-authored A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, he is now updating Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide.

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,