Printed in Germany but co-authored by a Swiss sociologist-photographer and a Taiwanese cultural researcher who both reside in China, China at its Limits tackles a topic as equally complex as its authors’ backgrounds.

The previous publication by Matthias Messmer and Chuang Hsin-mei (莊新眉), China’s Vanishing Worlds, looks at how the rise of China is affecting its countryside, providing “a rare opportunity to glimpse China as it once was, and as it will soon no longer be.” China at its Limits broadens the scope, exploring China’s relationships with its neighbors, especially in regard to life in the border regions.

“We wrote this book mainly to help readers understand the complexities and contradictions that China is struggling with in its ascent to superpower status,” the authors state in the introduction.

It’s a tricky topic, as China’s relations with these nations have mostly been uneasy in recent history — especially with Taiwan, which only receives a segment within the book’s eighth and final chapter, “The China Seas and Beyond.” It’s true that Taiwan doesn’t really have an inhabited “borderland” with China, but is a segment enough to explain the nuances of life here under China’s mushrooming shadow?

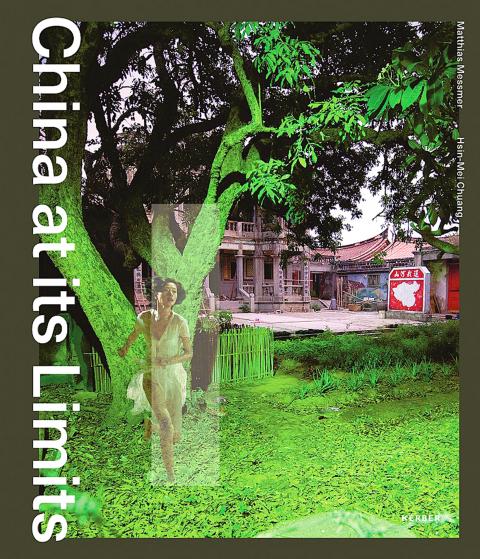

Despite Taiwan’s small part in the book, a photo from Kinmen is featured on its cover, with a map of Chinese Nationalist Party-era China (which includes Mongolia and Taiwan) in the background under the words, “return my lost land.”

At the very least, the book does not bow to Chinese propaganda, which is made clear with Taiwan shown as a country in the map on the first page. Like its predecessor, this book is also a “protest against the loss of memory,” much of it lost to China’s rapid development but, as the authors acknowledge, some conveniently erased by the government when “diverse viewpoints become a hindrance.”

Furthermore, Messmer and Chuang declare their neutrality in the preface: “China at its Limits does not strive to reach specific conclusions or serve a political or ideological agenda,” they write. “We are not foreign-policy strategists who see prediction as part of our job. But, based on our many years of research and study, we believe that China’s rise will probably be less peaceful than its leadership proclaims and hopes.“

The book, while comprehensively explaining the rise of China, does not glorify the phenomenon and in fact remains skeptical in tone throughout the book, pointing out that there are many “unidentified factors” behind Beijing’s “plans and hopeful dreams.”

The preface also states that this book will focus on the human aspects of the subject, and promises to stir the reader’s “feeling of empathy for human beings affected by the vicissitude of world politics.” The evocative photographs that make up a large part of the book mostly feature candid snapshots and intimate portraits, giving faces to the lively, personal and sometimes philosophical prose that at times reads more as informational travel musings, complete with a “places for the curious” section in each chapter. The captions for these photos are more than descriptions, and include context and the authors’ experiences on scene, further emphasizing the human experience.

The authors do a thorough job in explaining the history, economics and politics in these border lands, but also place great value on the unique and often little-known cultures that thrive in these areas, far from the influence of the country’s booming metropolises. They also experiment with photo montages juxtaposing past and present, select poems and quotes to go with certain scenes and muse on topics such the possibility of the “nothingness in history,” creating a unique product that is highly informative yet creative, aesthetically pleasing and most importantly, fascinating to read.

The first mention of Taiwan in the introductory chapter, however, is a questionable statement: “What, for example, is life like on the border separating countries that once teetered on the brink of nuclear war, as was the case with China and both the Soviet Union and Taiwan?” War has always been a looming possibility between China and Taiwan, and Taiwan did try to develop nuclear weapons in the past, but it’s a stretch to state that the two countries were “on the brink of nuclear war.”

In any event, the book delivers on its promise of the human aspect, as the first chapter — featuring North Korea — begins with an anecdote about how a Chinese woman refers to the hermit kingdom’s leader Kim Jong-un as “Fatty the Third,” while charging them for a peek across the border via telescope.

The prose alternates between personal experience, information and analysis, continuing into the “places for the curious” section where the authors detail their encounters and observations in selected locations on both sides of the North Korean-China border that illustrate different aspects of local life.

The most valuable part of these sketches are the actual conversations with local residents, from authorities following them and asking them to delete their photos and the sentiments of the grandson of “North Korea’s Greatest Chinese Hero,” to the Chinese Korean who openly proclaims her disdain for North Koreans. Each chapter ends with a “lingering question,” in this case, China’s role in the defection of North Korean refugees and its opportunities for migrant North Korean workers.

The book moves on counterclockwise to Russia and Mongolia, the sensitive areas of Xinjiang and Tibet and their neighbors, Southeast Asia and finally, to China’s interests in the South China Sea.

While Taiwan is mentioned in the greater context of Chinese maritime expansion, including the multi-national territorial disputes over a number of tiny islands, its section begins with an Internet forum quote from “hardcore Chinese military hawks.”

“There is one thing more urgent than recovering the islands and reefs in the South China Sea — namely, uniting Taiwan with the motherland.”

While brief, the authors do a balanced job in describing what they call “the tragedy of Taiwan, an international orphan,” where life seems to carry on as usual but “nothing betrays the fact that peace could break down at any time, especially in light of growing Chinese military threats.”

The fluctuating recent relations between China and Taiwan are thoroughly explained, as well as the recent development of a unique Taiwanese identity unrelated to China.

Interesting comparisons are made. The erosion of democracy in Hong Kong, for example, provides Taiwan plenty of reasons to worry about “excessive mainland influence,” and how Taipei is willing to reflect on its not-so-glorious past of authoritarian rule and political persecutions while Beijing still refuses to do so. They even manage to find the rare Chinese person who does not favor unification, and conclude that it would be risky for China to force democratic Taiwan to submit to “rigid Communist rule.”

In line with the theme of the book, more space is dedicated to a section on the borderland between Xiamen and Kinmen, a place where bombs still fell regularly from China up until 1978. It’s a poignant vignette of life on a sleepy island where life has been nothing but extraordinary due to its strategic location, with a population that have often felt like “second-class citizens on a minor island of a marginalized country.”

While this review focuses on the book’s treatment of Taiwan, don’t pick it up just because Taiwan is mentioned in it. China at its Limits is a rare, comprehensive picture of China’s peripheries that will provide a fuller understanding of the rise of China, a pressing topic that anyone with an interest in the region should brush up on, not to mention that the authors have put great effort into making it also an entertaining read.

In Taiwan there are two economies: the shiny high tech export economy epitomized by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) and its outsized effect on global supply chains, and the domestic economy, driven by construction and powered by flows of gravel, sand and government contracts. The latter supports the former: we can have an economy without TSMC, but we can’t have one without construction. The labor shortage has heavily impacted public construction in Taiwan. For example, the first phase of the MRT Wanda Line in Taipei, originally slated for next year, has been pushed back to 2027. The government

July 22 to July 28 The Love River’s (愛河) four-decade run as the host of Kaohsiung’s annual dragon boat races came to an abrupt end in 1971 — the once pristine waterway had become too polluted. The 1970 event was infamous for the putrid stench permeating the air, exacerbated by contestants splashing water and sludge onto the shore and even the onlookers. The relocation of the festivities officially marked the “death” of the river, whose condition had rapidly deteriorated during the previous decade. The myriad factories upstream were only partly to blame; as Kaohsiung’s population boomed in the 1960s, all household

Allegations of corruption against three heavyweight politicians from the three major parties are big in the news now. On Wednesday, prosecutors indicted Hsinchu County Commissioner Yang Wen-ke (楊文科) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), a judgment is expected this week in the case involving Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and former deputy premier and Taoyuan Mayor Cheng Wen-tsan (鄭文燦) of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is being held incommunicado in prison. Unlike the other two cases, Cheng’s case has generated considerable speculation, rumors, suspicions and conspiracy theories from both the pan-blue and pan-green camps.

Stepping inside Waley Art (水谷藝術) in Taipei’s historic Wanhua District (萬華區) one leaves the motorcycle growl and air-conditioner purr of the street and enters a very different sonic realm. Speakers hiss, machines whir and objects chime from all five floors of the shophouse-turned- contemporary art gallery (including the basement). “It’s a bit of a metaphor, the stacking of gallery floors is like the layering of sounds,” observes Australian conceptual artist Samuel Beilby, whose audio installation HZ & Machinic Paragenesis occupies the ground floor of the gallery space. He’s not wrong. Put ‘em in a Box (我們把它都裝在一個盒子裡), which runs until Aug. 18, invites