Aug. 14 to Aug. 20

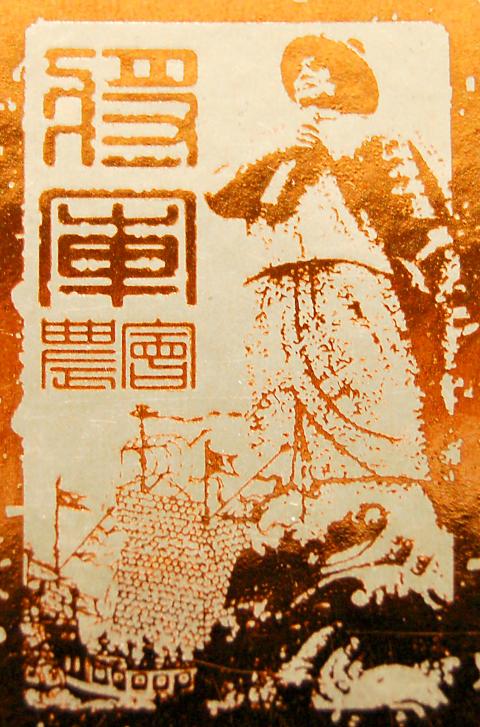

Shih Lang (施琅) waited 32 years for revenge. By that time, the man who ordered the deaths of Shih’s father and brother had been long dead — but his grandson, Cheng Ke-shuang (鄭克塽) remained on the throne of the Kingdom of Tungning (東寧), based around present day Tainan.

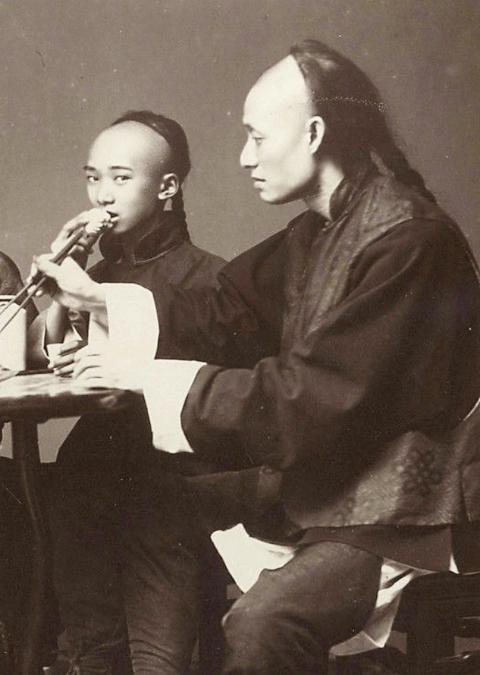

On Aug. 18, 1683, Shih accepted Cheng’s surrender on behalf of the Qing Empire. He watched as Cheng and his officials shaved the front of their heads bald and braided the back into a queue. Cheng’s adoption of the standard Qing hairstyle symbolized the end of his kingdom, which lasted a mere 21 years.

Photo courtesy of Public Television Service

Shih had a long history with the Cheng family, starting in his early 20s when he served as a top commander in Cheng Ke-shuang’s great-grandfather Cheng Chih-lung’s (鄭芝龍) pirate crew. The entire crew surrendered to the Qing in 1646.

Shih soon defected to join Cheng Chih-lung’s son, Cheng Cheng-kung’s (鄭成功, also known as Koxinga) anti-Qing army. In 1651, he defected again to the Qing after a dispute with Cheng. In response, Cheng ordered the deaths of Shih’s father and brother.

BATTLE OF PENGHU

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Shih was determined to exact revenge, but by 1662, Cheng Cheng-kung had retreated to Taiwan and established a kingdom with the aim of overthrowing the Qing Dynasty. He died that same year, succeeded by his son Cheng Ching (鄭經).

In 1664, Shih convinced the Kangxi Emperor to let him attack Taiwan, but the army was turned back by a typhoon. He tried two more times the next year to the same result.

Shih insisted on continuing the fight, but the emperor preferred to negotiate peacefully, citing that it was a treacherous journey that did not guarantee success. Shih refused to yield until the emperor stripped him of his military post in 1668 and assigned him a position in Beijing.

Photo: Chen Yi-min, Taipei Times

Shih waited 13 years for his next chance. In 1681, Cheng Ching died and the kingdom fell into disarray due to a succession conflict.

Qing official Li Guangdi (李光地) endorsed Shih to lead the expedition, stating, “His family was killed by Cheng, which will likely ensure his loyalty to the Qing. He is familiar with Taiwan and its surrounding seas, and he possesses strategic skills and isn’t just a rash man.”

In June 1683, Shih led a force of about 300 warships to Penghu, defeating new king Cheng Ke-shuang’s forces in little over a week. With heavy losses during the battle and low morale among both the Tungning troops and civilians, Cheng agreed to surrender.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Cheng, along with other Tungning nobles, officials and soldiers, were taken to Beijing. Cheng was given a hereditary title and died 24 years later.

TO KEEP OR NOT TO KEEP

After getting rid of the thorn in its side, the Qing Empire debated what to do with Taiwan — even though Cheng’s empire at most stretched from today’s Pingtung County to Changhua County, hardly sufficient to represent the entire nation.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Most officials, including the emperor, seemed to be keen on not taking over Taiwan, citing that it was an insignificant speck of faraway land. The general consensus was that either outcome wouldn’t affect the empire much. Some voices even suggested relocating Taiwan’s entire Han Chinese population to China and leaving it to the Aborigines and interested foreign powers.

But we already know that Shih was a persistent man. He wrote several detailed reports to the emperor, citing Taiwan’s strategic location and abundant resources, adding that if left unchecked Taiwan could either become a hotbed for pirates or be retaken by the Dutch. He further suggested that the troops sent to Taiwan could engage in farming, thus not straining imperial resources.

The emperor accepted his suggestion. On April 14, 1684, Taiwan became part of the Qing Empire’s Fujian Province.

Shih highly restricted immigration to Taiwan, forbidding migrants to bring their families — which resulted in many men marrying Aboriginal women, accelerating the sinicization of many plains tribes. He also banned people from eastern Guangdong Province, including Hakkas, as he believed that many were Cheng sympathizers. This reportedly led to a shift in Han Chinese demographics in Taiwan and domination by those of Fujianese ancestry, although the Hakkas started arriving again later as restrictions relaxed. Of course there was also illegal immigration.

It’s said that Shih and his followers became quite wealthy by claiming much of the farmland owned by the people of Tungning whom he deported to China. Other reports show that he collected tribute from Penghu fishermen, which he pocketed. These behaviors cause some historians to question his true motives.

Shih’s legacy has been the subject of much debate in both China and Taiwan, and one can only wonder what would have happened to Taiwan if the emperor didn’t heed Shih’s advice. But even so, the Qing never did much with Taiwan. Despite the arrival of officials and troops, the empire did not start seriously developing Taiwan until the 1880s — only to lose it to Japan in 1895.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades