Oct.24 to Oct. 30

In August of 1911, various Aboriginal Sediq chiefs from the Wushe (霧社) area, including Mona Rudao, were taken on a one-month trip to Japan, where their colonial masters made a display of power by having them tour various major cities and military facilities.

By then, the Sediq tribes in Wushe had already suffered much since the Japanese entered their lands in 1906. One of the major conflicts, writes Dakis Pawan in his book The Truth Behind the Sediq and the Wushe Incident (又見真相: 賽德克族與霧社事件), was the confiscation of all rifles during the first phase of the occupation, which were crucial to the Aboriginal hunting way of life.

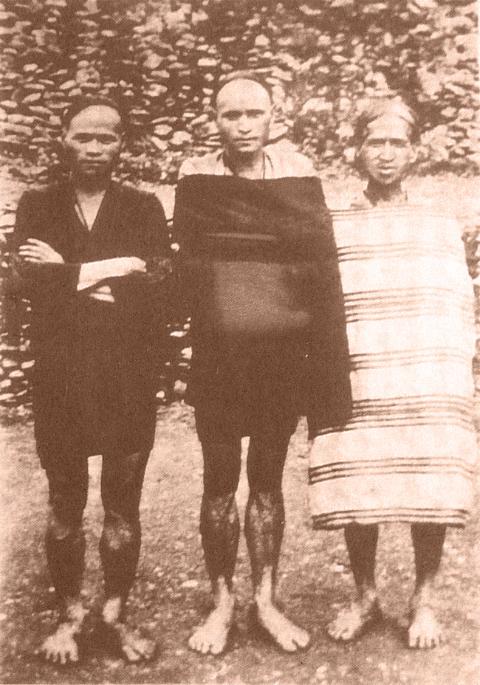

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“They killed every person who refused to hand in their rifles … they treated us like animals,” Takun Walis, a descendant of Wushe villagers states in the book, noting that by 1912 the population in Wushe had been reduced by half.

He adds that this was one of the factors that led to Mona Rudao’s planning of the Oct. 27, 1930 uprising, now known as the Wushe Incident (霧社事件), where hundreds of Sediq warriors descended on an athletic meet on at the local elementary school and killed 134 Japanese.

While Japanese official records point to direct causes such as police misconduct and even cite the inherent savage nature of the Aborigines, Dakis Pawan writes that resentment had been brewing for decades and the incident could have happened much earlier if not for the chiefs, who “did everything they could to prevent the young tribal members from killing Japanese.”

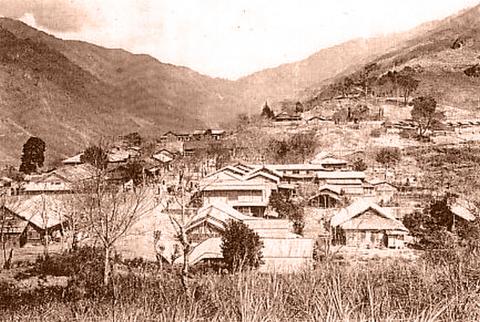

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“The [tour of Japan] did achieve a certain amount of success, because when the chiefs came back, they all agreed that ‘Japan has an enormous population with a strong military force,’” Dakis Pawan writes.

THE JAPANESE SIDE

Historian Leo Ching analyzes the official Japanese version of what caused the incident in his book, Becoming Japanese: Colonial Taiwan and the Politics of Identity Formation, using an official Japanese report of the incident published in 1934.

The common version of the event points to a confrontation between Mona Rudao’s son and a Japanese police officer as the trigger. A brawl ensued and the officer was beaten. The tribe’s later apology to the officer was not accepted, and rather than wait for official punishment, Mona Rudao called for the surprise attack.

Ching notes that the role of the policeman in Aboriginal society during the Japanese colonial era was very different from that of Han Chinese areas. There was a much higher concentration of officers in the Aboriginal areas, whose role was to “instill awe and dread of imperial authority.”

Other police functions that Ching cites include maintaining order and discipline, playing the role of teacher, doctor and general counsel as well as reporting census information such as births and deaths, and even climate and logging activities to the colonial government.

In a general sense, the report blames the inherent nature of Aborigines, citing their “natural propensity for violence,” “lack of guilt-consciousness” toward headhunting as well as their innate “infantilism, stupidity and stubbornness” and “ignorance of civility.”

Regarding the direct motives, the report attributed Mona Rudao’s actions to the failed marriage between his sister and a Japanese officer, and his son Bassao Mona’s to a marriage dispute where he had to carry out a headhunting ritual to demonstrate his bravery. It also discusses Aboriginal fears of reprisal for the police officer’s beating, and delves into police misconduct and Aboriginal discontent over construction projects on their land, low and delayed wages and other forms of mistreatment.

The report concludes by directly linking Aboriginal resentment to the construction and labor issues and the agitation of a few “rebellious savages.”

“By characterizing the incident as a circumstantial and personal effort, the colonial officials aimed to deflect any interrogation and criticism of colonial authority itself,” Ching writes.

YEARS OF RESENTMENT

But for the Sediq, it goes way deeper. Dakis Pawan writes that after killing many men and disarming the population, the Japanese “turned to high-pressure and unreasonable administration, aggressively building construction projects while disregarding our traditional ways of life and forced our people to work like horses.” They also abused the village women, and would burn down the houses of noncompliant villagers, killing their entire families.

It should be noted that the Japanese version of events stated “low and delayed” wages while Dakis Pawan’s account states that they were not paid at all. And as the Japanese account stated, there were issues with the policemen marrying Aboriginal women and then abandoning them.

Finally, Dakis Pawan states that “everything the Japanese did violated our gaya,” which roughly means the cultural, social and moral way of life that each Sediq member was strictly bound to.

“Because the protection of the tribe and our traditional areas is the basis of the perpetuation of gaya, just the fact that the Japanese occupied our lands was enough for my ancestors to use gaya to punish the invaders.”

“It’s hard for me to imagine that my ancestors would rather die in glory and use such measures against the Japanese, but at the same time I am not surprised,” he concludes.

This is the first of a two-part series commemorating the anniversary of the Wushe Incident. Next Sunday, Taiwan in Time will be looking at the aftermath of the incident as well as the shift in Japanese colonial policy toward Aborigines.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Oct. 21 to Oct. 27 Sanbanqiao Cemetery (三板橋) was once reserved for prominent Japanese residents of Taipei, including former governor-general Motojiro Akashi, who died in Japan in 1919 but requested to be buried in Taiwan. Akashi may have reconsidered his decision if he had known that by the 1980s, his grave had been overrun by the city’s largest illegal settlement, which contained more than 1,000 households and a bustling market with around 170 stalls. Fans of Taiwan New Cinema would recognize the slum, as it was featured in several of director Wan Jen’s (萬仁) films about Taipei’s disadvantaged, including The Sandwich

“Wish You Luck is not just a culinary experience, it’s a continuation of our cultural tradition,” says James Vuong (王豪豐), owner of the Daan District (大安) Hong Kong diner. On every corner of Kowloon, diners pack shoulder-to-shoulder over strong brews of Hong-Kong-style milk tea, chowing down on French Toast and Cantonese noodles. Hong Kong’s ubiquitous diner-style teahouses, known as chachaanteng (茶餐廳), have been a cultural staple of the city since the 1950s. “They play an essential role in the daily lives of Hongkongers,” says Vuong. Wish You Luck (祝您行運) offers that same vibrant melting pot of culture and cuisine. In

Much noise has been made lately on X (Twitter), where posters both famed and not have contended that Taiwan is stupid for eliminating nuclear power, which, the comments imply, is necessary to provide the nation with power in the event of a blockade. This widely circulated claim, typically made by nuclear power proponents, is rank nonsense. In 2021, Ian Easton, an expert on Taiwan’s defenses and the plans of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to break them, discussed the targeting of nuclear power plants in wartime (“Ian Easton On Taiwan: Are Taiwan’s nuclear plants safe from Beijing?”, April 12, 2021). The

Artificial intelligence could help reduce some of the most contentious culture war divisions through a mediation process, researchers say. Experts say a system that can create group statements that reflect majority and minority views is able to help people find common ground. Chris Summerfield, a co-author of the research from the University of Oxford, who worked at Google DeepMind at the time the study was conducted, said the AI tool could have multiple purposes. “What I would like to see it used for is to give political leaders ... a better sense of what people ... really think,” he said, noting surveys gave