Alex G, Beach Music, Domino

Alex G (for Giannascoli) upholds an indie-rock archetype that’s older than he is: the lo-fi introvert, sequestered in a bedroom, assembling songs with whatever equipment he has. The private, homemade songs can be as odd or obsessive as he wants. Then, somehow, word gets out. In the 1980s, it was via college radio and print media; for the 22-year-old Alex G, it’s online. Beach Music is his first album for a large independent label (Domino), but it’s his seventh full-length collection since 2010 to appear on his Bandcamp Web site.

He’s a throwback. Advancing technology gives home recordists huge artificial sounds at their fingertips, but Alex G prefers scraggly, mostly analog ones, the vocabulary of songwriters like Elliott Smith. (He also shares Smith’s fondness for waltzes that turn slightly dissonant.) In the studio, he layers on guitars (with finger squeaks on the strings) and keyboards, and he uses a drum kit more often than he uses machines. (One detail that separates him from 1990s lo-fi is his attentiveness to percussion sounds, captured without distortion and pinpointed in stereo space.)

Alex G’s narrators have often been traumatized, druggie, lovesick or inscrutable, and moving up the indie-rock circuit hasn’t made his new songs any more outgoing. Just the opposite: They are more cryptic and withdrawn. Most of Beach Music turns down from the rambunctious electric guitars of Alex G’s 2014 album, DSU, and his latest characters hint at the sociopathic: “Don’t make me hurt you/I’m watching you from here,” he sings in Salt, as his falsetto floats over undulating guitar chords and jittery percussion.

The music reflects the characters’ instability, with fluctuating meters and deliberately jerry-built arrangements. In Station, the high, gentle vocal of the opening verses is elbowed out of the way by a lower, rougher Alex G voice that takes over the song: “Please don’t look me in the eye/If you do, I think I might cry,” the intruder bawls. But even as Alex G sings about pulling back, the melodies and guitar lines persist, inducing listeners to stick around — if not to figure everything out, then to commiserate.

— Jon Pareles, NY Times News Service

The Agent Intellect, Protomartyr, Hardly Art

There are very few moments of release in Protomartyr’s imposing third album. It’s mostly gunmetal-gray, holding-pattern tense, with zaps of excitement on the way to more tension.

Listen to drummer Alex Leonard: For long stretches, he hits only snare and toms in mechanical patterns, and he rarely strikes an unclenched cymbal above medium force. Listen to guitarist Greg Ahee, whose ropy eighth-note lines and deep-echo, non-resolving, minor-seventh chords define at least half of this record’s rich atmosphere. And listen to singer Joe Casey. He talk-sings, he interjects, he protests a little, he repeats jaded phrases. (“They lie.” Or “They don’t see us.” Or “That’s not gonna save you, man.”) But he hardly ever shouts or builds to a peak. He’s like an inverse Bono. If you think it’s impossible to sound creative and defeated at the same time, you probably haven’t heard him.

Protomartyr is from Detroit, and there’s a dour, industrial affect to this record — the band’s best, although like the others it can sometimes feel like one long song — which seems to confirm everything you think you know about that city. The Agent Intellect is partly about Detroit as a place, with references to the Outer Drive and Jumbo’s Bar. But Casey’s excellent lyrics go bigger and more abstract: They’re also about Detroit as a pile of symbols and emotions. Asked recently by Stereogum what the themes of the record were, Casey listed 18 possibilities; the first four were “evil,” “false pride,” “lawyer billboards” and “dust.” That is a powerful index.

The list also included Alzheimer’s. Casey’s mother, Ellen, has that disease, and The Agent Intellect includes a kind of love song for her (and named after her), sung from the point of view of his deceased father, with the repeated line “I will wait.” Somehow, the song is not sentimental. It doesn’t do you that disservice.

— Ben Ratliff, NY Times News Service

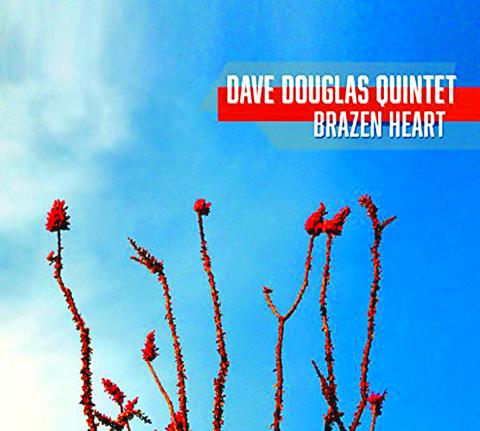

Brazen Heart, Dave Douglas Quintet, Greenleaf

A few years ago trumpeter-composer Dave Douglas released Be Still, a beautifully poignant album made in response to the loss of his mother. The album also formally unveiled his new band, a young quintet with the creative resources to hit the ground running. Brazen Heart, Douglas’ assured new release, showcases the same group at a more advanced stage in its evolution, as he again tries to transcend grief with art.

The album bears a dedication to Douglas’ older brother, Damon, who died in June after a long fight with cancer; Douglas made this album months before his brother’s death, in a style that proposes something flintier than an elegy. As on Be Still, there are soft-spoken interpretations of traditional hymns — the spirituals Deep River and There Is a Balm in Gilead — without a vocalist. (Be Still featured Aoife O’Donovan, winningly.)

Douglas is famously inclined to work on multiple projects at once: High Risk, his mindfully atmospheric fusion album with electronic artist Shigeto, appeared just months ago. But Douglas has long been particularly drawn to the acoustic postbop quintet as a delivery system for his music. His partners in this one are saxophonist Jon Irabagon, pianist Matt Mitchell, bassist Linda Oh and drummer Rudy Royston.

That these players have developed a vital shorthand, a band dialect, should be no surprise. Still, Brazen Heart clears a high bar for chemistry, starting with the bond between Douglas, with his jabbing chatter, and Irabagon, with his alert and gusty control. This front line works by cooperative tension with the rhythm section; at times, as on tracks like Wake Up Claire or Inure Phase, their outflow runs hot and cool at the same time.

— Nate Chinen, NY Times News Service

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

Imagine being able to visit a museum and examine up close thousand-year-old pottery, revel alone in jewelry from centuries past, or peer inside a Versace bag. Now London’s V&A has launched a revolutionary new exhibition space, where visitors can choose from some 250,000 objects, order something they want to spend time looking at and have it delivered to a room for a private viewing. Most museums have thousands of precious and historic items hidden away in their stores, which the public never gets to see or enjoy. But the V&A Storehouse, which opened on May 31 in a converted warehouse, has come up