The very few English-language blogs that mention Cijin District (旗津) describe it as an “island getaway” with “beautiful beaches.” But don’t be fooled by the bloggers, because this description of the tiny, narrow islet just off Taiwan’s southern port city of Kaohsiung is as frivolous as it is far-fetched.

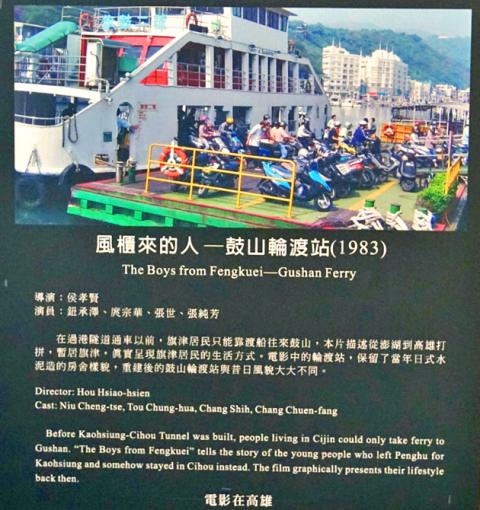

There’s a scene from Hou Hsiao-hsien’s (侯孝賢) 1983 blockbuster film The Boys from Fengkuei (風櫃來的人) which is shot at Kaohsiung’s Gushan Ferry Pier (鼓山輪渡) where dozens of tanned-skinned, harried-looking people are shuffling off a docked ferry carrying suitcases stuffed with crushed dreams. Today, replace the drifters with commuters on motorcycles and a smattering of Chinese tourists, and you’ll get much of the same vibe onboard the Gushan to Cijin ferry. Gritty and hardy, yes. Crisp and calm? Not so much.

TIME WARP

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

A dense layer of fog greets my travel party as our ferry approaches Cijin. On the bottom deck, motorcyclists position their vehicles as the lever is slowly lowered. Once the ferry is semi-moored, they race onto the harbor front, leaving behind clouds of exhaust fumes in the faces of startled tourists trying to disembark.

As you walk along the harbor, you’ll notice that the barges sailing by carry more cargo than people, and despite the fog, colorful containers sitting in shipyards in Kaohsiung’s Yancheng District (鹽埕) are easily discernible from across the grayish-blue waters.

Tourist gimmicks aside, Cijin is what I imagine it would be in the ‘80s — musty and grimy but brimming with character. Most residents are employed in the shipping industry, as was the case generations before, but there are hints of tourism and gentrification creeping in. Coffee trucks sell fresh-brewed cappuccinos and lattes to out-of-towners. Seafood restaurants beckon passersby with flashy displays of live oysters in tanks. Rickshaw bicycles, once a predominant mode of transport, are now available for rent on an hourly basis.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

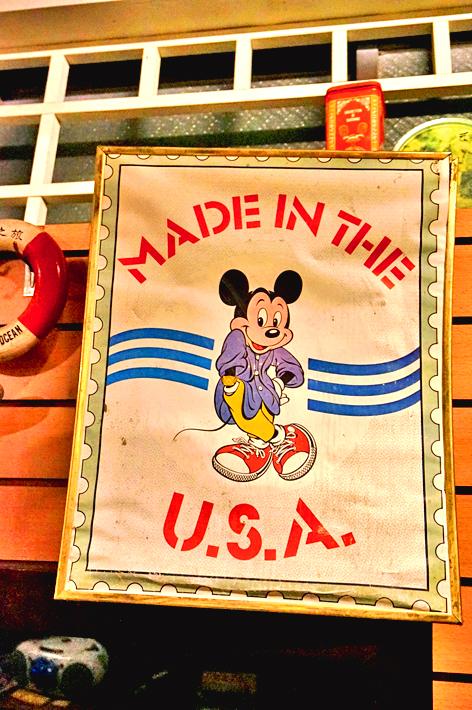

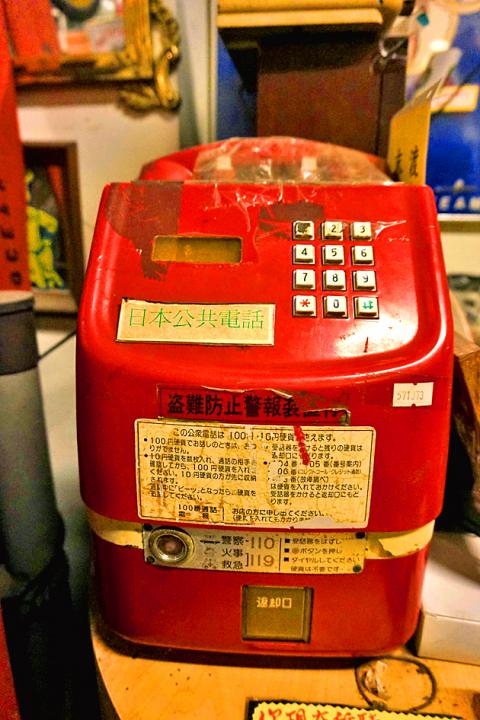

Leading to the main beach area are winding streets filled with small shops selling seafaring antiques, old bicycle parts and other quirky knick-knacks. What piqued my interest most, however, were the antiques. Amidst the dangling oil lamps and steering wheels propped against the shop walls, there are hundreds of collectibles that come from different countries and different time periods. These include compass locators from the UK dating back to the early 1900s, rusted Japanese phones from the colonial era in Taiwan and telegraphic machines from World War II. In other words, these unassuming shops are a treasure trove for maritime history nerds.

If you’re wondering how antiques from far ends of the world landed on in Cijin, the answer rests atop of Cihou Mountain (旗後山). Here, you’ll find the historic Cijin Lighthouse (旗津燈塔) which was built in 1883 by the British as part of an agreement signed under the Treaty of Peking (北京條約) in which Qing rulers were forced to open Kaohsiung’s port to foreign trade. The lighthouse was revamped in 1916 during the period of Japanese rule into the baroque white facade that’s seen today. Although it’s a bit of a trek, the lighthouse offers great aerial views of the harbor while evoking the feeling of a bygone colonial era.

SEAFOOD BY THE SEASHORE

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

Cijin Beach itself is not the cleanest or loveliest of Taiwan’s beaches, but it has its own story to tell. While there are not many people in the water during the winter months, there are plenty playing by the shore with their jeans rolled up just enough so that they can feel the cool water lap up against their feet. Wooden planks protrude onto the sand from the paved walkway, creating ideal picnic spots for couples to canoodle as they watch the sunset.

The black sand shoreline stretches for kilometers with rocky mountain ranges marking the curvature of the district. Because of the fog, only the lights from passing ships seem to make the horizon distinguishable. As the sun sets, the fog and sky fuses into an off-violet hue.

If you somehow find yourself stranded on Cijin by missing the last ferry, food is not something you’ll be worrying about. Locals in beach towns around Taiwan like to boast about the quality of their seafood, but Cijin has some of the freshest I’ve sampled.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

The restaurant we dined at was further south from the ferry terminal, about a 15-minute taxi ride down Cijin 2nd Road (旗津二路) with nothing but a few restaurants and houses along the way. My travel companion, a Kaohsiung native, apologized for the ambiance of our restaurant, Seashore Seafood (海濱海產). At the table next us, a boisterous family downed glasses of Taiwan Beer, picked their teeth and chatted loudly in Hoklo (more commonly known as Taiwanese).

There were no need for apologies, though, because it was the quintessential Cijin dining experience — no frills, just pure gastronomical bliss. We feasted on an assortment of salmon sashimi, spicy clams, salty calamari and mountain-grown vegetables with anchovies. It was a good balance of spicy and savory with the freshness of the sashimi to liven and neutralize our palates.

In addition to Seashore Seafood, there’s a wide selection of seafood restaurants lined up one after another throughout Cijin, most of which you can’t go wrong with. Small vendors also sell the usual night market delicacies like stinky tofu and fried squid on skewers, as well as papaya milk smoothies.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

Cijin may not have the most pristine beaches but the scruff and grime make it what it is — a seafaring port with much to be proud of in terms of its maritime history, a relaxed but hardworking lifestyle and, not to mention, some of the most delectable seafood.

Don’t plan to stay overnight though — there are a few hostels but nothing spectacular and nightlife is nonexistent. Most visitors stay in Kaohsiung and hop over to Cijin for a day trip, leaving before the last ferry departs at 10pm.

Getting there:

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

‧ Take the south-bound high speed rail (HSR) from Taipei Main Station to the last stop, Zuoying (左營). The ride takes approximately two hours.

‧ Cijin District (旗津) is accessible through a 10-minute ferry ride from Gushan Ferry pier (鼓山輪渡), near Sizihwan Station (西子灣) on the last stop of the Kaohsiung MRT orange line.

‧ One-way tickets cost NT$15, or NT$20 with a motorcycle. The last ferry from Cijin District to Gushan departs at 10pm.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

‧ Alternatively, if driving, the cross harbor tunnel connects Kaohsiung to Cijin District at the end of Cijin 1st Road (旗津一路).

What to see:

‧ Various seafaring antiques and bicycle shops

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

‧ Cijin Lighthouse (旗津燈塔)

‧ Cijin Beach

‧ Seafood restaurants

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

What to bring:

‧ Bathing suit, towel, insect repellent, change of shoes (walking shoes and flip flops), camera

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,