John Bayley, writer, critic and formerly husband of Iris Murdoch, died on January 12, aged 89.

John Bayley was one of the kindest, funniest and most perceptive people I’ve ever met. I’ve found these qualities in other people, but to find them all in the same man was astonishing.

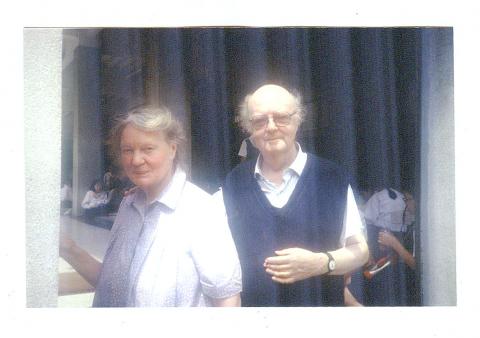

I spent six days with Bayley and Murdoch in Bangkok in 1995. They were there as special guests for the SEA Write Awards, an event honoring Southeast Asian authors, and I’d been assigned to interview them.

Photo: Bradley Winterton

All participants had been given rooms in the Oriental Hotel, and on my first evening I was invited down to meet them. They were sitting in the lobby, and from the start Bayley was markedly effusive. Perhaps I was fortunate to have had as my tutor Wallace Robson, a colleague of Bayley’s at Oxford when he was Warton Professor of English.

“Iris, our friend was Wallace’s student. Fancy that!” He was only later to reveal in one of his books that Robson had in fact been one of Iris’s many lovers before her marriage.

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Photo: Bradley Winterton

After that there was no stopping us. But it soon began to dawn on me that all was not entirely well. I began to suspect that Bayley had a secret agenda — Iris was to be kept in the conversation as far as possible, and anything that might be seen as boosting her self-esteem was to be seized with both hands. It wasn’t until the spring of the following year that he announced that his wife had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease.

The next day they were due to go up-river to Ayutthaya, the ancient Thai capital. I’d been before so arranged to meet them for dinner. I’d begun to realize I wasn’t going to be short of chances to chat. The recipients of the awards that year were mostly youthful Marxists, and Bayley had already confronted them at a seminar by quoting the observation of Keats that people weren’t too keen on writers who had a “palpable design” on them.

Dinner that night was a buffet on the Oriental’s riverside terrace. The river was close to flood-level and was lapping against the edges of the terrace’s slatted floor. How like something in an Iris Murdoch novel, I wrote in my notebook. But Bayley was pressing on me another glass of the excellent Beaune we were drinking.

Photo: Bradley Winterton

“Perhaps you’d be good enough to go and get Iris some apple pie and ice cream,” he said. “That’s what she really likes.” No apple pie was in evidence, but I did see some rhubarb crumble, something of a surprise there in the Bangkok. I went back to the table and informed Bayley of the situation.

“Oh,” he cried, almost jumping up from his seat in boyish delight. “Iris — rhubarb crumble!!! That’s b..b..better than ever!”

The next day I began to interview Iris, at around 10am in their rooms. These were the hotel’s Somerset Maugham Suite. “I’ve been reading some Maugham while we’re here,” Bayley had said earlier, “and while he was of course a terrible snob, he was also frightfully good.”

IRIS UNPLUGGED

They showed me the curtained four-poster bed (“Not terribly comfortable”) and the gloomy view from their sitting room’s near-subterranean windows. “Now I’m going to leave you two to get along on your own while I go for a little walk,” Bayley said. So I told Iris that I’d like her to talk about anything she liked. “Then I think I’ll tell you about my life,” she replied.

Forty or so minutes later Bayley returned. “How are you getting on?” he asked. “I’m talking about when I became a Communist,” Iris said. “Oh my goodness,” said Bayley, “then we’ll be here all day. Why don’t you just describe how you write your novels?”

Much of the plot was decided beforehand, she said, but not enough to impede the flow of inspiration. She wrote with a 30-year-old Mont Blanc fountain pen, sent the novel to her publishers in longhand, after which they typed it out, returned it, and she made corrections. She’d write all morning, and then again from 5.30pm to 8pm. Once she’d got a novel fixed in her head she’d write quite fast. She had a room where she wrote, but she could write almost anywhere.

She loved animals and would never harm one if she could help it. She was becoming Buddhist in her “simple way”, she said, loved the Thai temples, and wished she could have been brought up in such a religion.

She said she distrusted psychotherapist Carl Gustav Jung, but liked Thomas Mann and adored John Cowper Powys. She was reading his 1929 novel Wolf Solent there in Bangkok, and had read it several times before.

At dinner that night I described the effect one of Iris’s early novels, The Bell, had on me as a student. I’d been brought up on modernist texts like T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland with their implication that humanity’s glory lay in the past, and that the contemporary world was bleak and without resonance. But Iris’s novel suggested that the modern world was just as steeped in mystery and mythology as anything in Elizabethan England or Ancient Greece.

“Oh that’s wonderful!” Bayley said. I was pleased, of course, but later came to realize that what probably satisfied him was the boost the view gave to Iris’s self-confidence in her as yet unannounced condition.

It was at this dinner that I noticed that, though Iris was a vegetarian, Bayley would pick up a piece of, say, cold ham from his salad and deposit it on her plate, at which she would eat it as if not noticing.

I also mentioned The Wind in the Willows. “I know the whole book by heart,” Bayley said. I replied that I didn’t believe him. “Try me then,” he said. But I only laughed. Now I curse myself that I didn’t say “OK, Piper at the Gates of Dawn!” [a famous chapter in the book], and see what he came up with.

Later there was the presentation of awards by Thailand’s Prince Vajiralongkorn, the heir apparent. These took place at a formal dinner in the hotel but I didn’t have a suit. Bayley suggested I borrow one from the hotel — the receptionists were kitted out particularly smartly — and before long I was presented with a fine black jacket with an orchid in the buttonhole. Luckily I had a pair of trousers that matched it almost perfectly.

The evening proceeded as expected, though to see acolytes approaching Prince Vajiralongkorn up on the stage on their hands and knees was somewhat startling. In due course Iris made her speech, with Bayley standing beside her at a second microphone. All the award-winners then presented a copy of one of their books. Bayley had approached me that morning and said Iris didn’t have any of her books with her, and did I have one? I didn’t, but I slipped out to a bookshop on Silom Road and bought a paperback copy of The Bell. “Oh, just the ticket,” Bayley said.

The next day Bayley said “Why don’t you make them an offer for that nice jacket?” So I did, and the answer came back — £80 (US$122). “Eighty pounds!” Bayley exploded when he heard the news. “Eighty pounds?” I agreed I could probably get something similar made up anywhere in Asia a good deal cheaper; this was 20 years ago, after all.

“My goodness me,” Bayley said. “I bought this suit I’m wearing at an Oxfam shop for, I don’t know, but a great deal less than that!” I couldn’t help smiling at a former professor of literature at Oxford buying his clothes at what Americans call a thrift shop.

One morning we went to the Grand Palace where the body of the Thai king’s mother was lying in state. Bayley saw a very large bank of wreathes sent by the crowned heads of Europe and elsewhere. “I do hope our Queen has sent a good one,” he said, and proceeded to wade into the heap looking at the various labels. But the immensity of the task, and the heat, were too great, and I don’t think he found what he was looking for.

On another occasion we went for a dinner at the Jim Thompson House, and during the meal Bayley fumbled in his pocket and produced a lump of rather dry-looking brown bread. “Would you like some of this?” he said, “I saved it from breakfast. Thai food’s all very well, but sometimes we all need a little of what we’re used to.”

We also discussed A.E.Housman [author of A Shropshire Lad, 1896] and I brought up the question of Housman’s alleged masochism. Bayley said he thought there was indeed a masochist element in Housman. Having fallen in love and been rejected, he was determined to believe he couldn’t fall in love again, and so made himself endure the suffering of a lifetime. I said I’d read about him visiting Paris gay Turkish baths (as they were then called) in later life, and Bayley said he hoped he’d had some happiness or pleasure, but that his biographer had concluded there wasn’t enough evidence to be sure.

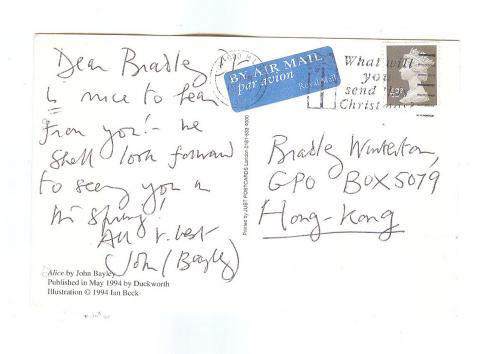

On another occasion he referred to his own novels, books such as Alice [1994] and The Queer Captain [1995]. They were slight things, even trivial, he said.

In the years that followed our Bangkok meeting I received several letters and postcards from Bayley, both before and after Iris’s death in February 1999. Here are some extracts.

Oct. 9, 1995

Dear Bradley, What a nice time we had! Seems like a dream now, as it always does, but a happy dream, of cats looking out of gorgeous gargoyles in royal palaces, and drinking our Beaune & the brimming river!

XX Love John & Iris

Dec. 19, 1995

How good to hear from you & have your sympathy. It’s not too bad, but I fear it is Alzheimer’s: and the saddest is at home, where Iris was always busy with a book & now is rather a ‘poor wandering one.’ I got a TV, which helps a lot. But sad …

XX John

XX Iris (yes, she did that bless her!)

Received May 8, 2002.

… The film [Iris, 2001] was absurd! But well done … Both the “me’s” were 6 foot (183cm) high with lots of hair — otherwise just like me, I’m sure.

… ‘Drowsy syrups!’ [Iago in Othello: “Not poppy nor mandragora/ Nor all the drowsy syrups of the world”]. No chance of those in present-day England, at least not for me — tho’ I’m interested your Taiwanese friends know little of them. It was the wicked Westerners of course! But oh dear, I should love to have enough of the stuff secreted away so I could leave the world when I want. I don’t care for the endless wait in the Departure Lounge! But “men must endure ...” as that tiresome Edgar says [in King Lear],

Yes, Buchan I’m sure influenced Tolkien — but Buchan is so much better! Iris’s enthusiasm for The Lord of the Rings used to amaze me — now they’ve got this dreadful film I won’t see.

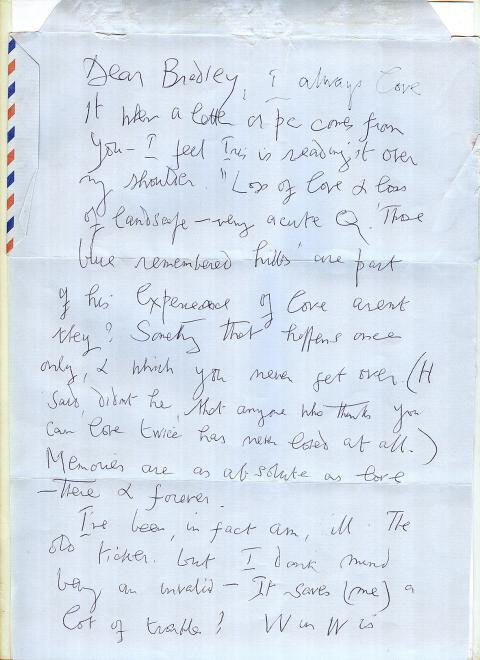

Feb. 1, 2007

When a letter or pc comes from you I feel Iris is reading it over my shoulder. “Loss of love & loss of landscape” [I’d asked him what he thought was the connection between these in Housman’s poetry]. ‘Those blue remembered hills’ are part of his experience of love aren’t they? Something that happens once only, and which you never get over.

I’ve been, in fact am, ill. The old ticker, but I don’t mind being an invalid — it saves a lot of trouble. Wind in the Willows is fading a bit in my mind now & I was looking for my copy the other day. Oh dear! XX

And that was the last I heard from him.

On one occasion in Thailand I’d raised the topic of eternal adolescents, and he’d retorted excitedly that he was one. If so, it’s clearly a wonderful thing to be. I’d also told him how I’d just been stuck in a traffic jam and the taxi driver had suggested we sing Jingle Bells. Bayley said he knew it too, and started to sing. There was a quality in him of living in the present, whatever it might turn out to be like, because it was all we had, and all we’ll ever have. Now he’s gone, I know I’ll be lucky to meet anyone again who’s anything like as engaging.

Quotations from John Bayley’s correspondence have been condensed and edited.

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

It was just before 6am on a sunny November morning and I could hardly contain my excitement as I arrived at the wharf where I would catch the boat to one of Penghu’s most difficult-to-access islands, a trip that had been on my list for nearly a decade. Little did I know, my dream would soon be crushed. Unsure about which boat was heading to Huayu (花嶼), I found someone who appeared to be a local and asked if this was the right place to wait. “Oh, the boat to Huayu’s been canceled today,” she told me. I couldn’t believe my ears. Surely,