Rose, Rose, I Love You (玫瑰玫瑰我愛你) takes place in the late 1960s. In China, Mao Zedong (毛澤東) is overseeing the Cultural Revolution. Meanwhile in Hualien County, a coastal village is busy with a little cultural revolution of its own. Upon discovering that American GIs are about to dock for rest and recuperation from the Vietnam War, the enterprising owners of four brothels rush to build a modern bar and to teach their prostitutes to make conversation in English.

But what begins as a simple plan to teach three phrases scales up wildly in proportion when Dong Si-wen (董斯文), a high-school English teacher, is appointed to teach the crash course for bar girls. Determined that the soldiers not leave Taiwan with a poor impression, causing “a great loss of face for the nation,” Teacher Dong decides to include instruction in American culture, global etiquette, singing and dancing, points of law, the art of tending bar and Christian prayers (“since all GIs are Christians” and probably need comforting), leading 50 bewildered prostitutes on a costly adventure.

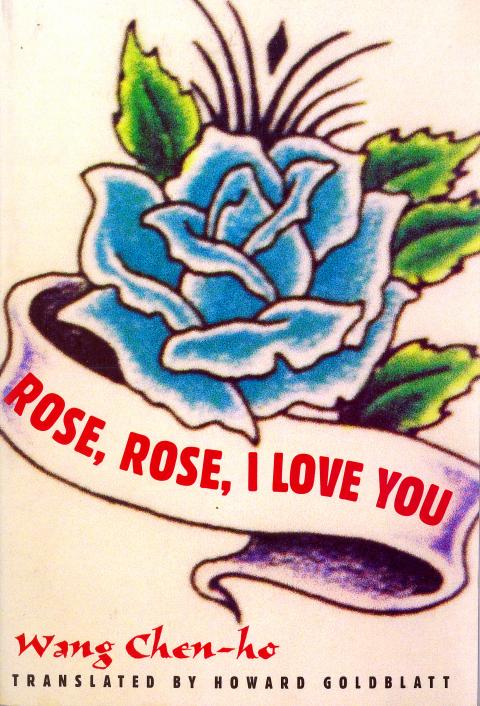

Originally published in Chinese in 1984, Rose, Rose, I Love You is the first work by Wang Chen-ho (王禎和) to be translated into English.

What makes Howard Goldblatt’s translation remarkable is that he’s able to smoothly reproduce much of Wang’s unusual dialogue, a blend of several languages.

The dialogue in Rose, Rose, I Love You mirrors the liminal state of language in Taiwan of the 1960s, which is right after Japanese colonialism but before Mandarin is fully adopted. Wang, whose characters use copious Hoklo (more commonly known as Taiwanese), peppers the novel with Minnan phrases like puichutchut (肥唧唧, “pleasingly plump”) and sainai (塞奶, “act petulantly”) and atoka (阿啄仔, “big-nose foreigners”). A-hen, a retired working girl, uses fragments of Japanese.

Goldblatt works gamely with Wang’s text, noting foreign words in italics so you can tell when Teacher Dong is trying to sound more refined by interspersing Mandarin with English (“Wonderful! Wonderful!”). He doesn’t always distinguish Hoklo words from Mandarin, but he cues beforehand when a passage of dialogue includes both. He also preserves most of the original wordplay, often by substituting parallel American phrases: The brothel owners know bopomofo (ㄅㄆㄇ), but pronounce it as “boar pour more” (補破網) in their Taiwanese accent. When Dong announces in English that they will conduct diplomacy “nation to nation, people to people,” the brothel owners hear it in Mandarin, the way Goldblatt renders it in brackets: “heart to heart, ass to ass” (內心對內心,屁股對屁股). His result is an English-language novel that successfully records language conflict in Taiwan, depicting how the way people speak declines to be subsumed under a single framework.

Rose, Rose, I Love You is also about the subversion of literary aesthetic.

Wang takes the device of epiphanies — which James Joyce uses to lead characters to great self-realization — and renders them as Teacher Dong’s “strokes of genius:” new ideas for the bar-girl crash course that only force the brothel owners to spend more money.

In two chapters, Wang applies the modernist technique of interior monologue. To present the day’s events, he uses the voice of brothel owner Big-Nose Lion and replicates Molly Bloom’s soliloquy in the final episode, Penelope, of Joyce’s Ulysses. But Big-Nose Lion is a burlesque parody: Molly is Joyce’s incarnate of the Great Mother, pure warmth and physicality, while Big-Nose Lion is a pimp who deals in the flesh. In Wang’s novel, Penelope — Molly’s mythical counterpart — is an English name that Teacher Dong later tries to bestow on one of the prostitutes, who derides it, “Aiyo! Whoever heard of an ugly name like Pian-ni-lao-mu [trick your old ma]?”

What emerges sounds like an acerbic rejection of the idea of uniform language or literary aesthetic: The text is like a hipster who tries on new clothes and makes them all look ironic.

It could also be a searching look at a protracted moment in Taiwan’s history — one extending to this day — of testing out many trappings of identity, often for the purpose of outside consumption. But the novel is open-ended, offering no glimpses of its true self: In the final scene, the prostitutes intone the Lord’s Prayer and Teacher Dong launches into a reverie: The Americans are coming, greeted by 50 world-class bar girls wearing cheongsams or eye-catching Aboriginal dress. The ladies sing the titular song, Rose, Rose, I Love You, first in Chinese and next in English. Each is a shimmering ambassador of an ethnic identity none wholly inhabits, and no one is so sure of who she is.

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,