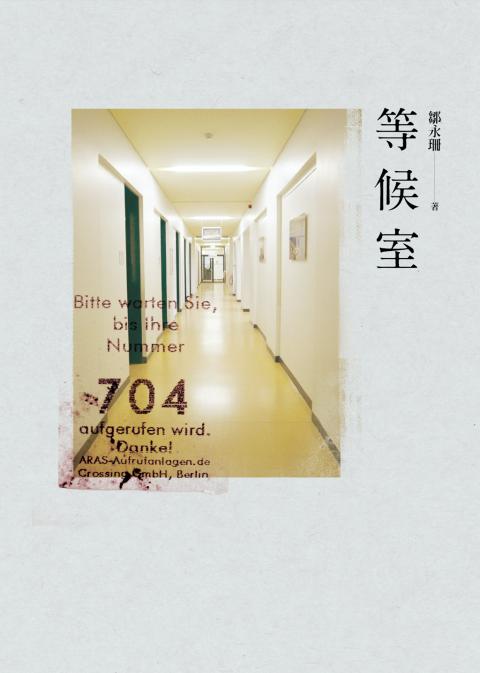

The life of Hsu Ming-chang (徐明彰) has dropped to a new low. He’s in Berlin, unable to appreciate its cultural riches, reeling from his divorce from a career woman for whom he had left Taiwan. His only source of income is freelancing for a Chinese-language publication. He speaks little German. Worse yet, his visa has expired, so he must make a trip to the waiting room of the Foreign Registration Office, where dreams are made and crushed with the same sterile detachment.

The Waiting Room (等候室), the Chinese-language debut novel of Tsou Yung-shan (鄒永珊), picks up at this juncture to follow Hsu as he navigates his visa troubles and the streets of Berlin.

Tsou, trained in mechanical engineering at National Taiwan University, is a new voice with an eye for fleeting detail. She picks out the tiny things that set Berlin apart, like how homeless men keep dogs, and renders them with a light and no-nonsense prose. She’s also expert at depicting the special miseries of the displaced person, such as the downgrade in social class, or how things that never cost a cent before are now painfully expensive — for instance, deep silences with a loved one over a pay phone. That’s Hsu calling his mother, of course — his ex-wife is back in Taiwan but doesn’t want to chat — and every expensive session leaves him feeling increasingly alienated from his home country.

Is his true home in Berlin? The question is open as Hsu struggles along in a foreign land, enrolling in a German class and cooking for himself for the first time. In another unprecedented move, he recoils from a series of bad housemates and springs for a little studio, the first personal apartment of his 32-year-old life.

The Waiting Room is clearly his bildungsroman, but he interacts with the locals, too, and eventually Tsou expands the stories of key auxiliary characters, all whom prove loosely connected to the Foreign Registration Office. Some, in their own ways, are alienated just like Hsu. There’s Mrs. Nesmeyanova, an immigrant from Minsk who becomes his landlady and housemate. She wants to leave Germany and go home, but can’t on account of an overbearing husband. Then there’s Ms. Meyer, an overweight and socially isolated German national who handles his visa request. Hsu feels put out because she treats him mechanistically like a number, as if that were a uniquely German thing. But it’s a people thing — unwittingly, he does the same thing to her, never learning her name and thinking of her, when the dreaded occasion requires it, simply as a fat German lady.

It’s with the cast of side characters that Tsou loses some of her gift for intimate details that build to match an absurd and unexpected reality. The weakest moments in the book are when Hsu meets, at separate times, a character named Christian and another named Christina and neither named Jesus, though they may as well have been for their weirdly wise dialogue and the tonic effect that it has on him.

Christian is a German who moves into the same building and listens to music turned up too loud, irritating all his neighbors except Hsu, who’s only intrigued. The two of them become friends and eventually lovers, and Christian teaches him that it’s not all right to let German phone companies scam him and that it is all right to ask for help.

Christina is a third-generation German Turk who meets Hsu by chance at her art exhibition at the Foreign Registration Office. She has thought a great deal about her identity as a German and as an ethnic Turk, which is believable, but her monologue — composed and grand like a personal statement for graduate school in sociology — is not. Despite that, their encounter is good for Hsu, who realizes that he is just like her, a thing caught between here and there. “Don’t be afraid. Chin up, back straight,” Christina concludes, unknowingly repeating Christian’s words of counsel, in one of the more aggressively placed coincidences of the novel.

At this point the plot is awkward, but it is an unusual disruption from a mostly elegant narrative. In a way, Christina performs a service, leading the reader to clumsily zoom out above the minutiae of Hsu’s life, so that his story is not exactly the story of a Taiwanese man, but a hopeful narrative about someone who learns to be comfortable with feeling uncomfortable. Perhaps, Christina/Tsou suggests, so long as people continue to grow, where home is will continue to be an open question.

The Waiting Room, a recommended title in this year’s Taipei International Book Exhibition, won a translation grant from the Taipei Book Fair Foundation and is being translated into English by professor Michelle Wu (吳敏嘉) of National Taiwan University’s Department of Foreign Languages and Literature. The work is scheduled for completion this year.

In Taiwan there are two economies: the shiny high tech export economy epitomized by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) and its outsized effect on global supply chains, and the domestic economy, driven by construction and powered by flows of gravel, sand and government contracts. The latter supports the former: we can have an economy without TSMC, but we can’t have one without construction. The labor shortage has heavily impacted public construction in Taiwan. For example, the first phase of the MRT Wanda Line in Taipei, originally slated for next year, has been pushed back to 2027. The government

July 22 to July 28 The Love River’s (愛河) four-decade run as the host of Kaohsiung’s annual dragon boat races came to an abrupt end in 1971 — the once pristine waterway had become too polluted. The 1970 event was infamous for the putrid stench permeating the air, exacerbated by contestants splashing water and sludge onto the shore and even the onlookers. The relocation of the festivities officially marked the “death” of the river, whose condition had rapidly deteriorated during the previous decade. The myriad factories upstream were only partly to blame; as Kaohsiung’s population boomed in the 1960s, all household

Allegations of corruption against three heavyweight politicians from the three major parties are big in the news now. On Wednesday, prosecutors indicted Hsinchu County Commissioner Yang Wen-ke (楊文科) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), a judgment is expected this week in the case involving Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and former deputy premier and Taoyuan Mayor Cheng Wen-tsan (鄭文燦) of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is being held incommunicado in prison. Unlike the other two cases, Cheng’s case has generated considerable speculation, rumors, suspicions and conspiracy theories from both the pan-blue and pan-green camps.

Stepping inside Waley Art (水谷藝術) in Taipei’s historic Wanhua District (萬華區) one leaves the motorcycle growl and air-conditioner purr of the street and enters a very different sonic realm. Speakers hiss, machines whir and objects chime from all five floors of the shophouse-turned- contemporary art gallery (including the basement). “It’s a bit of a metaphor, the stacking of gallery floors is like the layering of sounds,” observes Australian conceptual artist Samuel Beilby, whose audio installation HZ & Machinic Paragenesis occupies the ground floor of the gallery space. He’s not wrong. Put ‘em in a Box (我們把它都裝在一個盒子裡), which runs until Aug. 18, invites