As you may already know — since most of the prerelease publicity has been done in character — Sacha Baron Cohen’s latest comic avatar is Admiral General Aladeen, despot of Wadiya, a fictitious North African country, and the subject of The Dictator. Aladeen, whose desert nation is a gilded monument to his own vanity, is a (perhaps only slightly) exaggerated cartoon of strongmen like Moammar Gadhafi and Saddam Hussein, but with certain identifying features strategically blurred.

“I am not an Arab,” he says at one point, and The Dictator, directed by Larry Charles, carefully avoids references to Islam. Is this precaution enough to prevent the movie from giving offense? Probably not. But it may be enough to turn the tables on anyone who decides to take offense, which is really the point.

There is nothing especially outrageous here. The movie’s blend of self-aware insult humor, self-indulgent grossness, celebrity cameos and strenuous whimsy represents a fairly standard recipe for sketch-comedy-derived feature films. Baron Cohen, a nimble performer, long of face and limb, is like a cross between a camel and a chameleon. He seems capable of an almost infinite range of voices and appearances, all of them outlandish, and all of them at least potentially funny.

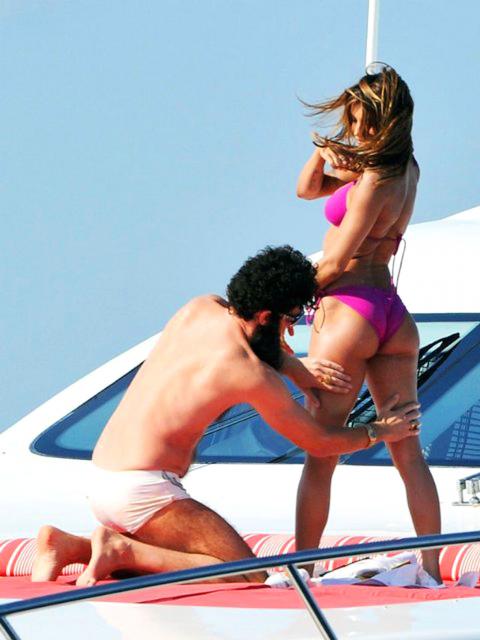

Photo Courtesy of UIP

That potential is mostly squandered in The Dictator, which gestures halfheartedly toward topicality and, with equal lack of conviction, toward pure, anarchic silliness. Aladeen, having alarmed the world with his human-rights abuses and his nuclear ambitions, is summoned to New York to address the United Nations.

There, thanks to the scheming of his Uncle Tamir (Ben Kingsley) and the ministrations of a US agent (an uncredited John C. Reilly), he finds himself replaced by a moronic double (also Baron Cohen) and forced to wander the streets like an ordinary nobody. He meets a wide-eyed activist named Zoey (Anna Faris), who gives him a job at her food co-op, and finds a sidekick (Jason Mantzoukas), who used to be one of Wadiya’s top scientists.

All of which would be fine if the jokes were better. There are a few good ones, but many more that feel half-baked and rehashed. There is, for example, a long scene in a restaurant frequented by Wadiyan refugees in which Aladeen, hoping not to be recognized, invents a series of false names for himself.

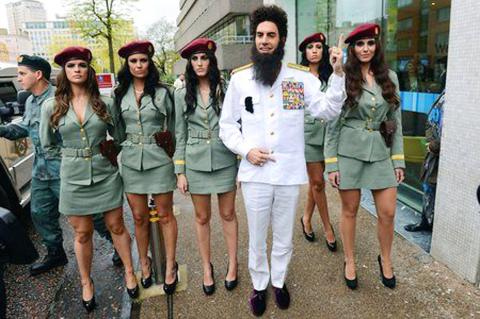

Photo Courtesy of UIP

Each name is a crazy mispronunciation of a sign in the restaurant — “Ladies’ Wash Room,” and the like — and every time he comes up with a new one, the camera pans over to the sign, just to make sure we understand what’s going on. And in case we’re slow on the uptake, the waiter (Fred Armisen) keeps insisting, “That’s a made-up name.” The joke is repeated at least four times.

Either this is the kind of meta-gag that tries to milk a laugh out of its own failure, or it represents a profound lack of confidence in both the material and the audience. Either way: So what?

Occasional attempts at post-Sept. 11 political satire fall just as flat, and supplying Aladeen with a love interest forces Baron Cohen to try sincerity, something for which he has no particular aptitude. Since women in his comic universe exist to be made fun of, rather than to be funny, Faris’ talents are pretty much wasted. Zoey is the target of Aladeen’s abuse, and also of the film’s scattershot misogyny, which is, like the dictator himself, conveniently disguised. When Aladeen calls her a “lesbian Hobbit” or recoils at the sight of her unshaved armpits, we’re really laughing at what a jerk he is. Aren’t we? Sure we are.

Photo Courtesy of UIP

Unlike his precursors Bruno, Borat and Ali G, Admiral General Aladeen is not meant to fool anyone into thinking that he is real, so viewers are denied the full measure of smugness that is Baron Cohen’s special gift to bestow. In the earlier projects (Da Ali G Show and the movies Borat and Bruno), viewers were invited to chuckle at the appalling idiocy of Baron Cohen’s characters and also at the stupidity of the suckers who took his buffoonery at face value.

When Borat, the cretin of Kazakhstan, carried a bag of his own feces to the table at a genteel dinner party, the joke lay both in the outrageousness of his behavior and, somehow, in the dismayed — yet still curiously polite — reaction of his US hosts. We could laugh at his grossness, secure in the knowledge that we weren’t really xenophobic because we were also sneering at the fools falling for the trick. Dumb hicks. Dumb foreigners. Thank goodness we’re not bigots like them!

As repellent as this logic may be in retrospect, it at least provided a queasy jolt of excitement. Something – sensitivity, good taste, the nonaggression pact between comedians and the public – was being put at risk. And there was, beyond the nervy displays of satirical hostility, a dimension of goofy absurdism that sometimes (more in Borat than in Bruno) approached the level of sublimity. Very little of that happens here, and the main insult of The Dictator is how lazy it is.

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,