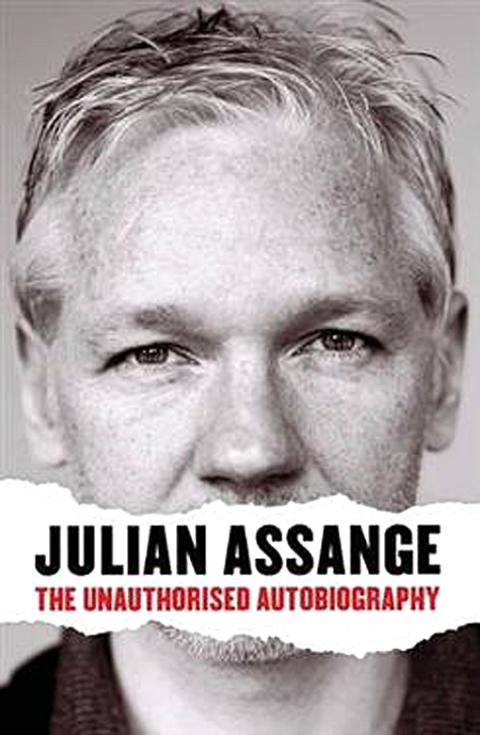

An unauthorized autobiography, it has to be said, is an unusual category. What it means for Julian Assange: The Unauthorised Autobiography is that Assange agreed to write his life story, in collaboration with the UK journalist Andrew O’Hagan, but asked to be released from the contract after the first draft was completed. Seeing that he’d already received an advance, and that that had been spent to pay for legal expenses, the publishers, Canongate, decided to go ahead and publish what they had.

With 38 other publishers worldwide waiting to issue their own editions, Canongate’s decision is certainly understandable.

But the view of this reviewer is that Assange has little to worry about. The book reads not only well but in many places magnificently. If you want a version of the WikiLeaks saga from the horse’s mouth, and in addition a defense of press freedom in the tradition of John Wilkes, Tom Paine and Daniel Ellsberg, this is undoubtedly it.

As WikiLeaks is built on a belief in unfettered access to information, one expects as much of the truth as can be fitted into 250 pages from Assange. (The last 100 pages or so consist largely of extracts from the leaks themselves, generally less sensational than one might have expected.) There’s one fact of local interest close to the start — the name Assange, taken from the author’s stepfather, derives from the Chinese Ah Sang, the stepfather’s ancestor several generations back, who was “a Taiwanese pirate.”

START AT THE END

The story begins with Assange’s thoughts while on the way to London’s Wandsworth Prison in December last year, an incarceration he was released from nine days later. It then proceeds to narrate his life story from childhood until that release.

The book is characterized by carefully calculated plain-speaking, and it’s hard not to believe everything Assange says here. Near the end he describes — for the first time, he states — the events that took place in Sweden in August last year that led to the request for his extradition from the UK. He reports making love to two Swedish women and to his being uncertain whether the subsequent police involvement was due to jealousy on one or both their parts or was some kind of “honey trap.” He’d been warned that a smear campaign based on alleged sexual impropriety might be resorted to by some of his highly placed enemies.

A similar openness characterizes his account of his activities as a 20-year-old in Melbourne hacking into some of the world’s most secure computer systems. He was convicted of an offense at the time and fined. He notes how he was then, with an online name taken from the Roman poet Horace, one of perhaps only 50 people worldwide engaged in such a high level of technical security breaching. “As experiences of young adulthood go,” he writes, “it was mind-blowing.”

LEAKS

Once he comes to the WikiLeaks years, you’re treated to accounts of the leaks relating to, among other things, Somalia, Guantanamo, Fallujah, Kenya, Scientology, a Swiss and an Icelandic bank, the far-right British National Party, and the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Every page is of absorbing interest. The wording feels considered, and there’s no evidence at these points of this being merely a first draft. Only at the very end, when Assange describes the differences that developed between him and the Guardian and New York Times, does the tone begin to appear hurried.

It looks as if it was at this stage in the book that Assange began to have doubts. It is, after all, recent events that are most difficult for anyone to describe in an even-handed way.

The release of, and reaction to, the infamous video of the Baghdad shooting from a US helicopter gunship, originally dubbed by WikiLeaks “collateral murder,” makes for extremely painful reading. All modern warfare is here, you feel — the pressure for “contact,” the civilian victims, the unacknowledged pattern of computer games. But the horror that Assange rightly feels is nonetheless conveyed in prose that is, it seems to me, both appropriately outraged and responsible.

Assange makes many strong points in the book — that politically he’s neither right nor left, that he isn’t anti-American (he points out that Anwar Ibrahim’s political party in Malaysia, which he aligned himself with, was supported by the US), that the history of journalism is a history of leaks, and that essentially WikiLeaks is simply “anti-bastard.”

BREAKING EGGS

But he does point out that you can’t bring about change with a polite consideration for the feelings of all others, because change is something those already in power will always resist, and sometimes vigorously. But he forcibly rejects the accusation that he and WikiLeaks have blood on their hands.

The Iraq War material was subjected to a blanket computer program that deleted all names and other identifying information, he states. Nevertheless, WikiLeaks has in place a program that, if its work ever becomes impossible, ensures that all remaining material will be released, presumably unedited.

He’s also disarmingly frank about himself. “I am some kind of weirdo,” he admits. He’s someone, he says, who likes a scrap and generally lives unconventionally — out of a backpack much of the time, and at one point owning only one pair of shoes.

The book’s main weakness lies in the refusal to consider that centers of power are essential to all societies, and that diplomacy can never be successfully conducted in the public eye. But WikiLeaks has only sometimes concerned itself with diplomatic material, and in recent releases has more often focused on the horrors of war. This is something that governments throughout history have been anxious to conceal, but in the age of the Internet (which to Assange is necessarily the age of Everyman) it seems to me something we all ought to know about. Anybody who comes near to sharing this viewpoint will be unable to resist this book.

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

It was just before 6am on a sunny November morning and I could hardly contain my excitement as I arrived at the wharf where I would catch the boat to one of Penghu’s most difficult-to-access islands, a trip that had been on my list for nearly a decade. Little did I know, my dream would soon be crushed. Unsure about which boat was heading to Huayu (花嶼), I found someone who appeared to be a local and asked if this was the right place to wait. “Oh, the boat to Huayu’s been canceled today,” she told me. I couldn’t believe my ears. Surely,