Located in a lane near Yongkang Park in Taipei, Changyifang’s (彰藝坊) mission is to continue three generations of work with budaixi (布袋戲), or Taiwanese traditional puppet theater, and introduce the art form to a new audience.

The studio was founded by husband-and-wife team Chen I-tzu (陳羿錫) and Chen Tsung-ping (陳宗萍). The two met when Chen I-tzu, whose grandfather and father were puppet performers in Changhua County, was brought in to serve as a consultant on an exhibition called The Beauty of Taiwan Theater (台灣戲劇之美) at a gallery where Chen Tsung-ping worked.

Seeing the small, intricately made budaixi puppets was a revelation, Chen Tsung-ping says. While growing up in Yunlin County she had watched “golden light” (金光) puppet shows, which feature medium-sized puppets, at temple fairs. She was also familiar with puppet television shows like the popular Pili (霹靂) series, but Chen Tsung-ping says she had never seen traditional handmade glove puppets and didn’t even know they were part of Taiwanese culture.

Photo: Catherine Shu, Taipei Times

“I was so surprised and curious. The puppets are so exquisite and lovely to look at, and I wanted to let more Taiwanese people, our people, know about them,” she says.

“In puppetry,” Chen Tsung-ping adds, “you see all these traditional arts, like embroidery, carving and performing, preserved. I studied art and I know if you don’t understand your own traditions, you cannot create new things.”

After marrying, the couple founded Changyifang, named after Changyiyuan (彰藝園), the puppet troupe Chen I-tzu’s father founded in Changhua County more than 80 years ago.

Photo: Catherine Shu, Taipei Times

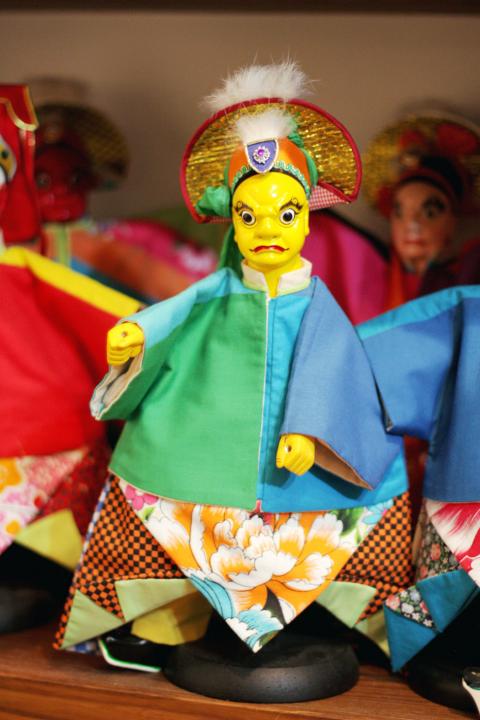

As soon as visitors walk into Changyifang’s combination studio-storefront, they are greeted with an explosion of colors: The company’s bags and accessories come in a rainbow of bright hues and lively patterns, including Taiwan floral cloth. Puppets are carefully arranged on shelves, with cards in English and Chinese explaining the characters’ backgrounds. Sheng (生) are male puppets of different ages, professions and temperaments, while female characters are called dan (旦). Others represent historical and literary characters, such as figures from The Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

At the time the couple met, Chen I-tzu was serving as a consultant for scholars and groups like the Seden Society (西田社布袋戲基金會), which seeks to preserve traditional puppetry. Chen I-tzu, whose great-grandmother, grandfather and father all worked with budaixi, helped researchers choose the right paint colors for restoring a puppet’s face or made sure that costumes for different characters were assembled properly. His great-grandmother began sewing puppet costumes during the Japanese colonial era to earn extra money, while his paternal grandfather and father both carved puppet heads and performed.

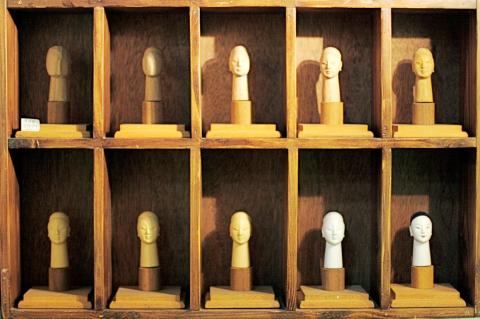

When he first began working with his family “it wasn’t so much that I was interested in puppetry, as it was that we had to make a living,” says Chen I-tzu, who keeps wooden heads carved by his father on display in his studio. When he slips his hand into a budaixi puppet, even for a few minutes to show it off to a visitor, the puppet springs to life. Its tiny hands greet the viewer with delicate gestures while its head angles daintily to the side.

Photo: Catherine Shu, Taipei Times

“When people became interested in preserving traditional puppetry, there was a need for people who are familiar with them because there weren’t a lot of specialists,” he says.

Changyifang’s puppets are handmade in Xiamen in Fujian Province, China, where the couple set up a puppetmaking studio. The two moved operations there soon after they opened Changyifang to keep production costs down and because they say they could not find craftspeople in Taiwan who were able to take on the extremely fine, richly detailed hand embroidery on each costume.

Each puppet takes about two months to finish. A step-by-step display set up in the Changyifang studio shows how the heads are carved, a process that takes a week. First the puppet’s face is shaped from a block of wood, and then the positions of different features are determined. Finally, the minute details that give each puppet its own personality, like hooded eyelids, flaring nostrils or an enigmatic smile, are carefully, gradually added.

Photo: Catherine Shu, Taipei Times

Hands and feet are coated with lacquer in layers until they are opaque and gleaming. Jing (淨) puppets have elaborately painted faces in vivid colors like red, black or blue that represent different character types. Costumes are covered with embroidered motifs and embellishments sewn in gold thread, instead of the sequins used on cheaper puppets. Many of Changyifang’s budaixi puppets are purchased by collectors and can cost up to NT$50,000; most range from NT$15,000 to NT$25,000.

Other puppet types represented at Changyifang include chou (丑), or clowns, and two categories the Chens created for stock characters frequently seen in Taiwanese puppet performances: xian (仙), or wise immortals who often serve as the voice of reason during conflicts, and the odd-looking guai (怪), who often have animal-shaped heads.

Some puppets have outfits made from Taiwan floral cloth, as a nod to puppet troupes that recycled worn curtains or bedding into costumes and stage decorations.

Photo: Catherine Shu, Taipei Times

Others show how budaixi has changed along with Taiwan’s history. One set of puppets wear Japanese military uniforms from the colonial era and are based on the puppets used in plays with anti-Japanese propaganda after the Chinese Nationalist Party took control of Taiwan. Mao Zedong (毛澤東) and Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) puppets in solid neon colors were made to appeal to collectors of designer toys and figures. One budaixi puppet in the couple’s collection was created for a short-lived puppet version of the cartoon Samurai Jack.

While most of their time is spent designing puppets and operating the studio, the Chens still occasionally put on puppet performances when the opportunity arises, including events organized by the Council for Cultural Affairs (文建會) or temple fairs. While most of the people who purchase Changyifang’s puppets are collectors, Chen Tsung-ping hopes the tradition will survive and continue to evolve with each new generation.

“You can make anything into a puppet,” she says. “It is a medium and you use your hands to bring the puppet to life, but there is no limit to what you can perform.”

Photo: Catherine Shu, Taipei Times

Photo: Catherine Shu, Taipei Times

Photo: Catherine Shu, Taipei Times

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

It was just before 6am on a sunny November morning and I could hardly contain my excitement as I arrived at the wharf where I would catch the boat to one of Penghu’s most difficult-to-access islands, a trip that had been on my list for nearly a decade. Little did I know, my dream would soon be crushed. Unsure about which boat was heading to Huayu (花嶼), I found someone who appeared to be a local and asked if this was the right place to wait. “Oh, the boat to Huayu’s been canceled today,” she told me. I couldn’t believe my ears. Surely,