Such is the charged magic of Annie Proulx’s prose that you might think there is no subject it cannot render luminous. But try Polygal. It crops up rather a lot in Proulx’s latest book and, no matter how hard she tries, she cannot make this particular brand of polycarbonate plastic sing. And it’s not Polygal’s fault, either. Much of Bird Cloud, Proulx’s first non-fiction book for 20 years, remains inert, as stubbornly charmless as the Wyoming wilderness in which it squats.

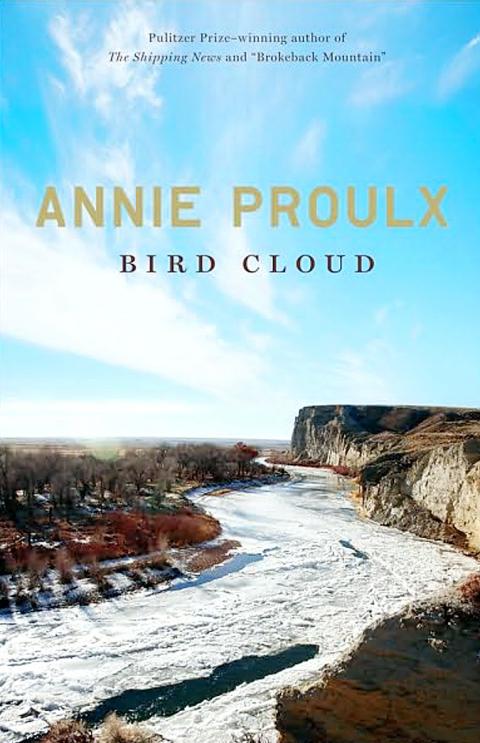

Bird Cloud is subtitled “a memoir” but anyone hoping that Proulx is going to reveal all will be disappointed. Instead what she offers is an account of two years in the middle of the last decade during which she attempted to build her dream house — aka Bird Cloud — on a plot of wind-scoured land strung out along the North Platte River. There’s trauma aplenty here, but not of the misery-memoir kind. Taps leak, the wrong building parts arrive and the state-of-the-art concrete floor turns a funny color. The Polygal creaks and snaps alarmingly in the night. The house that was intended as “a poem in wood” turns out to be more of an argument in expensively sourced materials from around the world.

All this might seem a long way from Proulx’s usual beat of exquisite ordinariness. In novels and short stories such as The Shipping News and Brokeback Mountain, her quiet, sinewy characters find their worlds split apart by disturbances far more profound than a dodgy boiler or misfiring color scheme. But while Proulx’s focus may have altered in its shift from fiction to autobiography, her style has not. As a result wrangles with soft furnishings are conveyed in that plucked prose she normally reserves for characters negotiating the overwhelming tides of geography and history. The effect is like one of those classy parlor games where you are required to rewrite the Highway Code in the style of Hemingway.

Of course, it isn’t all like this. Proulx, who is 75, has picked this patch of Wyoming for her dream home — rather than, say, a retirement complex in Florida — precisely because it is strung with those deep narratives of time and place that she has made her own. It turns out that her 263-hectare plot has been the stage for many a chapter of animal and human history. Volcanoes once erupted here and dinosaurs ambled; the Ute and Arapaho Indians made peace and war for centuries. And then in 1849 came the covered wagons, carrying hardscrabble families across the central plains of North America. Each migration left its trail in the form of displaced rocks, still-traceable tracks and buried ephemera. When Proulx isn’t fussing over the tatami matting in her meditation room, she likes to roam her scrubby estate with her husky builders, scratching for clues to the land’s previous tenants.

What, though, do the husky builders feel about this? Early in Bird Cloud Proulx immodestly declares that one of her good points is an ability “to put myself in others’ shoes constantly.” But on the evidence of this memoir she has an almost total lack of interest in the people subsumed in her all-consuming project. The builders, whom she turns into faux-cowboys by calling them “the James Gang,” don’t seem to have any choice when the lady with the checkbook demands that they down tools and help her hunt for arrowheads. Various contractors pass through the site and are rechristened according to her needs as “Mr Floorfix” or “Mr Solar.” Her family makes quick pitstops but, doubtless deterred by the drama of the apparently homicidal windows, sensibly continue on their way to somewhere more soothing.

Worse still is the tone of clumsily disguised self-regard that trickles into the corners of Proulx’s narrative. She does that annoying thing of constantly telling us how many books she has (“more than you” is the clear message). When, using her imported Japanese bath for the first time, there’s a massive flood into the library below, I found myself sneakily pleased. She also graciously lets us in on the special living requirements of internationally successful writers: they need attics to store their luggage because, you see, they are required to travel so much. Terrific stylist that she usually is, Proulx even lets slip such blushingly formulated musings as “I find innovative architecture extremely interesting.”

All this self-satisfaction might have been bearable had Proulx built a house which a) we could see and b) she could actually live in. But this is the sort of posh memoir that doesn’t include photographs, as if to deter the kind of slummy reader who likes to have a good old nose around people’s lives. And as for b), well, Proulx discovers halfway through the project that the road to Bird Cloud is impassable from November to March. This is tricky. So the upshot is that one of the world’s greatest writers has built an expensive summer cottage.

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,