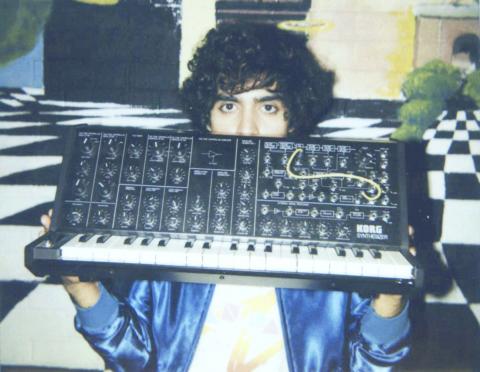

Mark Mothersbaugh, the keyboardist and singer of Devo, reminisced on Friday night about visiting the RA Moog Co’s synthesizer factory in Buffalo sometime in 1971 or 1972.

“It was like heaven,” he said.

He was onstage here at Moogfest, a three-day festival with more than 60 acts — bands and disc jockeys, theremin soloists and professed synthesizer geeks — to celebrate the Moog synthesizer, an instrument that transformed music by giving composers countless new sounds.

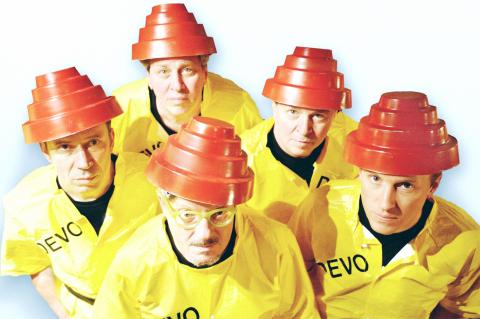

Photo: REUTERS

At the factory, Mothersbaugh said, he saw shelves holding rows of Minimoogs, the pioneering, suitcase-size synthesizer that was introduced in 1970 and made electronic music portable. It was, he declared, “the most futuristic thing I’d ever seen.”

That future was four decades ago, before digital synthesizers, laptop computers and smart phones put the tools for electronic music on desks and in pockets. Moog Music, as the company was renamed, is now in Asheville, in the mountains of western North Carolina where Robert Moog (pronounced to rhyme with “rogue”), the inventor behind the synthesizer, lived from 1978 until his death in 2005.

The nonprofit Bob Moog Foundation is raising money to build a “Moogseum” here based around Moog’s extensive archives, and it presented daytime panel discussions on the history of the synthesizer, featuring Moog’s collaborators and resurrecting some of his early equipment. A display case at the Orange Peel, a club commandeered by Moogfest, held a Minimoogseum: a history of the Minimoog and a playable theremin.

Photo: Bloomberg

The festival drew 7,000 to 7,500 people a day and offered five stages at places in downtown Asheville that ranged from clubs to arenas. Visitors saw many Moogs, recent and antique, come and go.

But Moogs were not mandatory for

acts wanting a festival booking. “It’s a thread, it’s not a box,” said Ashley Capps, whose company, AC Entertainment, produced Moogfest.

Matmos, an electronic duo whose brilliant set built terse loops into overarching, evolving structures — largely meditative, occasionally wry — confessed that it was using Roland synthesizers. There were also Korgs, Yamahas, Nords and plenty of unassuming laptops, many of them loaded with Moog samples, in a lineup oriented toward the electronic and the experimental.

Moogfest included rock (Massive Attack, Sleigh Bells, Caribou, Jonsi, MGMT, Thievery Corp.); pop (Hot Chip); funk (Disco Biscuits); hip-hop (Big Boi, El-P); and electronica both abstract and aimed at the dance floor (Four Tet, Pretty Lights, Bonobo, Jon Hopkins, Dan Deacon, Marty Party).

Moog’s original 1964 synthesizer — he called it the Abominatron — was bulky, balky and sometimes unpredictable. It was analog, not digital, creating sounds by sending a continuous electronic signal to a speaker, not a stream of numbers through a converter. To analog devotees that continuous signal is intrinsically superior to digital music, which reproduces sound with tens of thousands of samples per second, which means tens of thousands of infinitesimal gaps between them. Analog sound, said Amos Gaynes, Moog Music’s applications engineer, has infinite resolution, “down to the granular level at which reality is perceived.”

The first commercial Moog synthesizers could play only one note at a time, not always in tune. Early synthesizer users had no preset sounds to fall back on: They plugged in patch cords, turned knobs and experimented. A musician could create a sound, but the synthesizer had no memory; once the sound was changed, it was gone, possibly forever. Heat and humidity also affected the instrument. When digital synthesizers arrived, in the 1980s, sales and prices plunged for those primitive analog synthesizers. They seemed destined for obsolescence.

But not so fast. From their sometimes-unstable oscillators, filters and amplifiers, Moogs and other analog synthesizers produced sounds that more reliable digital synthesizers would not: buzzes, swoops, whooshes, scrapes, gurgles, screeches, burps, crackles and countless other onomatopoeia-worthy noises. Interactions among the waveforms that were generated by the oscillators, and modulated by waveforms from other oscillators, or from a noise generator, were often untamed. Turning a knob or wiggling a wheel on the Minimoog could radically change a timbre in mid-note, making it feel more handmade, less synthetic. Analog sounds are a funky corrective to sterile digital tones; colliding waveforms make a beautiful noise.

Moogfest was a festival of strange sounds and monumental beats, of drones and loops, and of synthetic tones that grew to feel natural. For extra oddity a good part of the audience wore Halloween costumes all weekend.

Neon Indian’s wistful pop marches emerged from thickets of staticky synthesizer noise and disappeared back into them. Panda Bear, from Animal Collective, sang high, chantlike melodies over unswerving synthesizer and guitar drones in what came to sound like cries from the heart. Omar Souleyman, from Syria, sang heartily about love and street life over booming 4/4 drumbeats, while his keyboardist simulated traditional Middle Eastern instruments on two synthesizers. Emeralds played one continuous, very gradually unfolding song, with Moog sounds rippling and percolating through it.

From their laptops and mixers, disc jockey-producers dispensed reveries and onslaughts. Saturn Never Sleeps, the duo of King Britt and Rucyl (both working mixers) backed Rucyl’s airy, echoing voice with fits and starts of percussion and a bass undertow. Mimosa played quick-change remixes, switching from verse to verse among harsh drumbeats, quasi-classical strings, even a little ragtime. Ikonika played a magnificently aggressive set of revved-up hyperdub, a blitz of drumbeats.

Moogfest even included unsynthesized music, in two sets of lapidary, elegant pop by Clare and the Reasons, who played Clare Muldaur Manchon’s songs and then backed up the elusive songwriter (and Beach Boys collaborator in the 1960s) Van Dyke Parks.

For younger bands, analog synthesizers are a means to summon and twist nostalgia. Moog sounds are inseparable from some of the most influential music of the 1970s: new wave, synth-pop, funk. Gerald Casale of Devo said in an interview that in Devo’s music “we called the Moog a poison gas vapor,” adding, “it was allowed to come in and swirl around and interject rude and random things that didn’t fit a rock ’n’ roll lexicon. We were hoping for that.”

At Moogfest, Devo was given the Moog Innovator award — and a new Minimoog Voyager XL, which combines analog modules with some digital conveniences. But Devo could not perform, because three days before the festival its guitarist, Bob Mothersbaugh (Mark’s brother) severely injured his hand. The Octopus Project — an Austin, Texas, band that infuses its rock with minimalist patterns and features a theremin — learned two Devo songs on the way to Moogfest and backed up Mark Mothersbaugh and Casale.

The original Minimoog benefited not only from its portability but also from a design flaw. Bill Hemsath, who was Moog’s chief engineer and the main inventor of the Minimoog, revealed that some specifications for the Minimoog’s filter section were incorrect, overdriving it by about 15 decibels. “Nobody caught it, and it went into production,” Hemsath said, adding that it gave the Minimoog a ferocious bass sound musicians soon exploited.

The synthesizer bass lines that pumped through 1970s funk — and have been recycled by hip-hop — were spearheaded by the keyboardist Bernie Worrell in Parliament’s 1977 song Flash Light using three connected Minimoogs; he has also received a Moog Award. Worrell performed at Moogfest with Headtronics, a trio with drumbeats and vinyl scratching from DJ Spooky and Freekbass on bass; he poked and teased at the melodies, making his Minimoog cackle and whoosh. “It’s a dinosaur, but you still can’t beat that sound,” he said in an interview.

The comeback of analog synthesis has been accelerated by software that simulates the interactions of the old oscillators, filters and amplifiers. Instead of pampering some aging (and increasingly expensive) equipment, computer users can, if they wish, turn an infinite number of virtual knobs and plug in an infinite number of virtual patch cords — and then, if they wish, output the digitally generated voltage through analog components. Moog Music recently released an iPhone app, Filtatron, that looks like classic Moog modules and creates similar sounds. “This is actually the best time in human history to be into analog synthesis,” said Gaynes the applications engineer.

At Moogfest, what once seemed primitive was claiming its own future.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and