Established in 1127 after a military collapse that precipitated the loss of its northern heartlands to the nomadic Jurchen people, the Southern Song Dynasty (南宋) was very much an empire on the defensive. This sense of being an island of civilization amid a rising tide of barbarism made it super sensitive to the achievements of Chinese culture, and even as it battled incursions on its borders, it took the glittering traditions of the Tang (唐) and Northern Song (北宋) dynasties and further refined them.

The Southern Song Dynasty, beleaguered militarily from without, and plagued by political dissension from within, produced artists who reached a pinnacle of creativity and technical skill that has, arguably, never been equaled.

The exhibition Dynastic Renaissance: Art and Culture of the Southern Song (文藝紹興 — 南宋藝術與文化特展), which opened last week in the main gallery of the National Palace Museum (國立故宮博物院), has brought together a staggering amount of material from this relatively short-lived dynasty (the Southern Song lasted 153 years before being overcome by the Mongols under Kublai Khan). To complement its own extensive holdings of Southern Song artifacts, the museum has arranged loans from 10 other institutions, including the Tokyo Museum and Kyoto National Museum in Japan, and the Shanghai Museum (上海博物館), Liaoning Provincial Museum (遼寧省博物院), Zhejiang Provincial Museum (浙江省博物館) and Fujian Museum (福建省博物院) in China. The exhibition comprises a total of 410 items spread over 10 galleries.

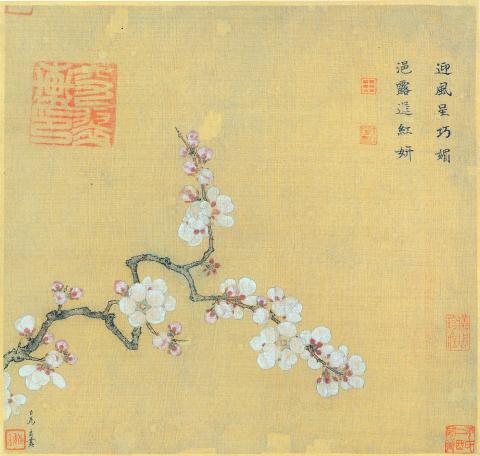

PHOTO COURTESY OF NPM

This is an important exhibition for anyone interested in Chinese culture, but perhaps more significantly still, it is very accessible for those without specialist knowledge. Credit must go to the curators who worked long and hard in the presentation and layout of the objects, and for the English language explanatory materials, which are more extensive and helpful than usual.

The most appealing aspect of the artifacts is the profound “humanism” that pervades Southern Song art. This is not a reference to the humanism of Enlightenment Europe, but more generally a sense of individuality and the importance of self-cultivation, aspects of Southern Song life that jive very closely with modern sensibilities.

A number of emperors during the Southern Song Dynasty were artists of the first rank, as in the case of Gao Zong (宋高宗), whose letter Imperial Order Presented to Yue Fei (賜岳飛手敕) is cherished not just as an important historical document, but for its outstanding penmanship, which combines a clear understanding of the finest calligraphic tradition with the charm of a unique personality. What’s more, one can even guess at the type of man Gao Zong might have been from the fine official portrait of the emperor that is included in the exhibition. He was one of the first Chinese emperors for whom we have trustworthy contemporary likenesses that go beyond merely ritual images of imperial dignity.

PHOTO COURTESY OF NPM

There are many other fine works of calligraphy on display, which apart from their artistic accomplishment, also provide an insight into the mixture of precariousness and self-belief that characterized the Southern Song.

Calligraphing Poetry (字書詩), written by the administrator and poet Lu You (陸游), is a calligraphic exercise of transcription that records ancient poems, which might otherwise have been lost.

Another interesting piece of calligraphy is the Letter to Shoichi Kokushi (無準師範與聖—國師尺牘), by the monk Wuzhen Shifan (無準師範), who expresses gratitude to Japanese Buddhist master Shoichi Kokushi for sending timber from Japan to assist in the reconstruction of the Jinshan Temple (徑山寺), which had been destroyed by fire. This work, on loan from the Tokyo National Museum and only on display until Nov. 23, is classified as a national treasure in Japan, and testifies to the important influence the Southern Song exerted even in the days before the dynasty’s final demise (the letter is dated 1242, 32 years before the dynasty fell).

Southern Song artists excelled in making guan (官), ceramic vessels decorated with the famous pale blue-green celadon glaze. The shape of many of these vessels imitates that of vessels traditionally made from bronze and used at formal state functions.

Impecunious and on the run from their aggressive northern neighbor, the Southern Song hadn’t the funds to create vastly expensive bronze ritual vessels, and passed the job of creating substitutes to highly talented master potters, who from unpromising materials sourced in the vicinity of the dynasty’s new capital at Lin-an (臨安), modern day Hangzhou (杭州), created a class of ceramic ware that is esteemed as some of the most beautiful ever made by mankind.

The ceramic vessels’ minimalist and impromptu beauty is immediately understandable in our contemporary setting — more so, indeed, than the bronze originals.

Another area where the Southern Song seem to be particularly modern is in the dynasty’s exploration of what might be variously described as a mannerist, decadent or minimalist style of visual expression. A particularly interesting explanatory diagram in the exhibition shows the shift from the central placement of the subject in a landscape painting in the Northern Song Dynasty, to asymmetrical compositions that increasingly emphasized either specific details or empty space as the Southern Song Dynasty progresses. Painters such as Li Song (李嵩) took this to extremes in paintings such as West Lake (西湖圖), in which the whole central area of the painting is left blank.

There are also many works that might almost be described as avant-garde in their forceful indifference to representational norms.

Immortal in Splashed Ink (潑墨仙人) by Liang Kai (梁楷) is informed by Zen Buddhist philosophy. Its boldly minimalist composition is expressive, especially when seen in the original, where every brush stoke is evidence of the artist’s physical engagement with the work.

There is much that is enormously spectacular in this show, but what is most surprising is the immediacy and power of the artifacts.

From its position of almost constant crisis, the Southern Song Dynasty created one of the most vibrant centuries in the development of Chinese art, and one that is particularly resonant today. While fighting for its life, the civilization discovered whole new forms of expression that continued to exert an influence on art in the succeeding centuries.

Above all, there is a transcendent sadness to the exhibition. Amid all this beauty, one thinks of the elusive lines from the late Tang Dynasty poet Li Shang-yin (李商隱), which, roughly translated, read: “The sunset is indescribably beautiful; alas, there follows the night” (夕陽無限好/只是近黃昏). For many of the Southern Song artists represented in this exhibition, the darkness of night was never far away.

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,