Chris Kotzian is a police dispatcher and his wife Barb is a graphic designer.

With two young children, a dog and a house in a suburb of Denver, Colorado, the Kotzians are much the same as any other busy, working family except for one thing. Both Chris and Barb have dwarfism and stand less than 1.2m tall.

Like many people with dwarfism, the Kotzians have worked hard to overcome social and physical barriers to lead full and normal lives, which includes working with non-profit group, Little People of America (LPA), to stop people treating them like a circus act.

In recent years reality TV shows, such as Little People, Big World and The Little Couple, that have shown people with dwarfism leading normal lives, have helped change attitudes but there is still a long way to go.

“I have gone to many elementary schools, which have little people in them, and talked to them about how I get along in this wonderful world, and how we are all the same inside and we all have differences outside,” said Barb Kotzian, who is the vice-president of their local chapter of the LPA.

“Some people wear glasses and some people have red hair, no one is the same, but we must remember we all have feelings and we must be kind to each other.

The Little People of America, which supports people of short stature caused by more than 200 medical conditions know as dwarfism, actively campaigns against people with dwarfism being portrayed in the media as no better than side show attractions.

The group (www.lpaonline.org), with more than 6,000 members, also opposes the use of such language as “midget” which is considered highly offensive.

It was at the group’s annual conference in 1999 in Portland, Oregon, that Chris and Barb first met. After dating long-distance for almost a year, Chris proposed and Barb moved to join him in Denver and they married in 2001.

“It’s very common for little people to meet their mate and have long-distance relationships,” Barb Kotzian said.

This year the group is holding its annual general meeting in Nashville in July after last year passing a resolution officially condemning the “M” word.

“For decades we’ve been trying to raise awareness around the world and prevent use of this word but this was the first time we took official action,” LPA spokesman Gary Arnold said.

“Slowly change is happening as there are a lot of programs now on TV including people of short stature and through that programming the message is sent about language and that people of short stature are just regular people who have dwarfism.”

“But it is still mostly on reality TV and it would be good to see more prime time dramas or sitcoms integrate people of short stature as regular characters or into the storyline.”

MODIFICATIONS AT HOME, SCHOOL AND IN CARS

The LPA has campaigned for years about the media portraying people with dwarfism in a bad light, with TV using them for stunt shows or as the brunt of jokes.

The Kotzians, who fully support the increased exposure that little people are now getting on TV, say they are fairly typical of the estimated 30,000 people with dwarfism in the US although they have a better life than many.

Studies have shown people with dwarfism are less likely to find work, earn less and struggle with low self-esteem.

Their height does, of course, mean certain adaptions are needed in their home and cars.

Chris has to stand inside his refrigerator to reach the top shelf. Barb goes from stool to stool to prepare a meal in her kitchen. They use special extenders on the brake and gas pedals of their car and most of their clothes need to be altered.

They dream of someday being able to improve their home with lowered sinks and light switches but such changes are costly and with a four-year-old daughter and six-year-old son they already have plenty of other bills to pay.

Both Chris and Barb have a genetic disorder called achondroplasia, the most common form of dwarfism responsible for 70 percent of dwarfism cases, for which there is no treatment.

They were both born from parents of average size. A new mutation of the gene responsible for their condition has been associated with increasing paternal age. Studies show that 80 percent of people with achondroplasia have parents of average size and it happens in about one of every 20,000 births. But it does not mean their children will also have dwarfism.

GREATER ATTEMPTS AT INCLUSION

A person with achondroplasia has one dwarfism gene and one “average-size” gene. If both parents have achondroplasia, there is a 25 percent chance their child will inherit the non-dwarfism gene from each parent and be average size. There is a 50 percent chance the child will inherit one dwarfism gene and one non-dwarfism gene and have achondroplasia.

But there is also a 25 percent chance the child will inherit both dwarfism genes, a condition known a double-dominant syndrome, which invariably ends in death at birth or shortly thereafter.

Chris and Barb’s son Adam is achondroplasic but their daughter, Avery, is average size.

“I call Avery my little, big girl, for she was so petite and tiny with being 5 pounds 4 ounces [2.4kg], but she was so long at 21 inches [53cm] long. Avery is now 4 years old, and has passed her brother in height,” said Barb who also dreams of setting up her own home business.

“She is his best pal though, and loves to help him, and idolizes his authority ... When they were the same height people thought they were twins. We are lucky though. Adam has a good communication value, and he stood up for himself and let people know he was the older brother.”

Barb and Chris have worked with the children’s school to ensure that Adam had the modifications needed, such as a stool by all drinking fountains, sinks and toilets, a special chair so that his legs do not dangle and fall asleep, and a door pull on classroom doors as he cannot reach the handles.

Arnold said the needs of children with dwarfism were being met more as awareness rose.

“There are far greater attempts at inclusion now than there were in the past,” said 39-year-old Arnold.

“During my early years in school in the 1970s I had leg surgery and needed to be in a wheelchair for three to four months and although my school was physically accessible I was sent to another school with more kids with disabilities.”

“Slowly people are starting to realize that disability does not change who we are. We should not be treated differently.”

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

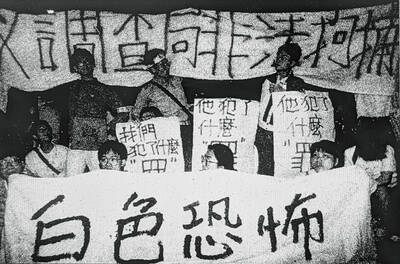

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

When life gives you trees, make paper. That was one of the first thoughts to cross my mind as I explored what’s now called Chung Hsing Cultural and Creative Park (中興文化創意園區, CHCCP) in Yilan County’s Wujie Township (五結). Northeast Taiwan boasts an abundance of forest resources. Yilan County is home to both Taipingshan National Forest Recreation Area (太平山國家森林遊樂區) — by far the largest reserve of its kind in the country — and Makauy Ecological Park (馬告生態園區, see “Towering trees and a tranquil lake” in the May 13, 2022 edition of this newspaper). So it was inevitable that industrial-scale paper making would

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing