Michael Moore, the most successful documentary filmmaker of all time, is thinking of getting out of the business of making documentaries.

Not right away. He’s got the sure-to-be-controversial Capitalism: A Love Story due in US theaters Oct. 2. But after that?

“While I’ve been making this film I’ve been thinking that maybe this will be my last documentary,” says the Flint native, who filmed and starred in such hits as Sicko, Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11. “Or maybe for a while.”

Those three films make up half of the top six documentaries ever made, according to boxofficemojo.com. Fahrenheit 9/11 is the highest earning documentary ever, with a domestic take of US$119 million.

But now he’s looking to branch out as a director.

“I have been working on two screenplays over the last couple of years,” he says. “One’s a comedy, one’s a mystery, and I really want to do this.”

Moore, 55, is sitting in the driver’s seat of a dark green van, parked behind the Old Opera House here on a Friday afternoon. He’s both frazzled and buzzed.

He’s just come from a public panel discussion with the Michigan Film Office Advisory Council, a cheerleading affair for the Michigan Film Incentives law and for the growth of the local film industry.

The discussion was part of the Traverse City Film Festival, celebrating its fifth year, which Moore created and which seems to grow exponentially each summer.

His wife, Kathy, is on the phone. He has to meet her for lunch and arrange some movie tickets for her folks.

Oh, and he has to deliver his first cut of Capitalism: A Love Story to the studio later that night.

If the movie does turn out to be his last documentary, some fans are sure to be disappointed.

“It would leave us with a big loss if he stopped making documentary films,” says Ruth Daniels, vice president for marketing for Detroit-area Emagine theaters, who remembers showing Moore’s films dating back to 1989’s Roger & Me.

“His documentaries do make quite a bit of money and he’s paved the way for documentary movies to become mainstream,” she says. “It will leave a void.”

For now, though, Moore is caught up in the enthusiasm of the festival, which ends today.

“This has been the best festival yet, certainly the smoothest run, the largest crowds,” Moore says.

At the panel discussion, Moore said the festival had 37 percent more sponsors this year and advance ticket sales were up 25 percent, despite Michigan’s economic woes.

Over the past five years, Moore said, the festival has sold a 250,000 movie tickets, and while he’s happy the crowds keep coming, he’s intent on keeping commercialism to a minimum.

Sponsorships are kept low-key, no commercials run before films, and industry wheeler-dealers — agents, buyers, distributors — don’t make their way to Traverse City, although many of the filmmakers do.

“My goal is to keep it as a festival for movie lovers. The fact that you can park your car and walk to all the venues, it has a real communal feel here,” Moore says. “You don’t want this to be Park City (home to Utah’s far more crowded and industry-oriented Sundance Film Festival).”

Unlike many cultural events, the festival seems to be wholly embraced by the town it’s in. Many of the moviegoers are local and more than 1,000 people volunteer at the festival.

Moore is working full time in northern Michigan now, although his perspective certainly hasn’t mellowed. In Capitalism, the director — who has explored America’s health care system, its propensity for gun violence and its journey to war in Iraq — is taking on nothing less than the American economic system.

“I thought, why don’t I just go for it and go right to the source of the problem — an economic system that is unfair, it’s unjust and it’s not democratic. And now we’ve learned it doesn’t work,” he says.

“This issue informs all my other movies. I started thinking if I can only make one more movie — I started thinking this of course during the Bush years — what would that movie be? And this is the movie.”

From his first film, Roger & Me, in which Moore roasted General Motors, his sense of humor and strong point of view have outraged many critics while drawing in huge audiences.

Moore says “objectivity is a nonsensical concept that’s really been misused” and that his approach to documentaries is to make sure they’re good, informative, entertaining movies first.

“The term documentary got pigeonholed a long time ago, and 20 years ago when I made Roger & Me, I guess my hope was to bust loose through that strict structure and perception of what a documentary should be and allow it to be everything any other work of nonfiction can be,” he says. “A nonfiction book can be a book of both fact and opinion, it can be just fact, it can be just opinion.”

“Humor is OK in a documentary. Before me, I was told it had to be castor oil. No, you’re making a movie; you’re making a piece of entertainment. You’re asking someone to leave the house on a Friday night to go to a movie.”

But time’s a-wasting and Moore has to dash off into his busy day. To pick up his wife. Pick up his in-laws. Grab some lunch. And then go finish what may be the last documentary he ever makes.

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

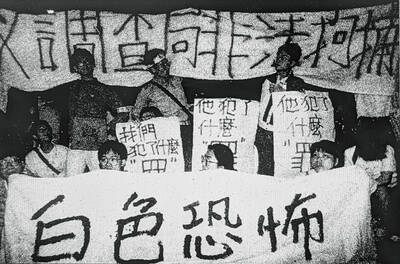

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

When life gives you trees, make paper. That was one of the first thoughts to cross my mind as I explored what’s now called Chung Hsing Cultural and Creative Park (中興文化創意園區, CHCCP) in Yilan County’s Wujie Township (五結). Northeast Taiwan boasts an abundance of forest resources. Yilan County is home to both Taipingshan National Forest Recreation Area (太平山國家森林遊樂區) — by far the largest reserve of its kind in the country — and Makauy Ecological Park (馬告生態園區, see “Towering trees and a tranquil lake” in the May 13, 2022 edition of this newspaper). So it was inevitable that industrial-scale paper making would

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing