Enter the British Museum’s new Egyptian gallery and you will be struck by a line of painted panels of unexpectedly rich coloring and extravagant composition. On one panel, a pair of naked female dancers, their fingers interlaced, glide sinuously before a crowd at a banquet. Beside them, a flute player stares out from the painting, her hair shimmering as if she is swaying to the music. Each figure is distinct, individual and freely drawn, their proportions and detail captured perfectly.

Wander further along the main wall and you will find other exuberant depictions of everyday life in 18th Dynasty Egypt: a boy driving cattle along a road; geese, stored in baskets, ready for the market; a farmer, stooped and balding, checking his fields; and a hunt through reed beds that burst with creatures — shrike, wagtails and pintail ducks — easily identifiable still.

These are the tomb paintings that once belonged to Nebamun, a court official who lived almost 3,500 years ago, and they are the greatest surviving paintings we have from ancient Egypt. Each was created for Nebamun by a painter as gifted as any of the Renaissance’s finest artists, and they will be revealed to the public this month when the British Museum opens a special gallery dedicated to them, a 10-year project that has cost US$1.38 million to complete. It will be a striking addition to the museum.

Yet for all the effort that has gone into the gallery’s construction and the studies of its paintings, mystery still shrouds the Nebamun panels. For a start, archaeologists have no idea about the identity of the artist who created them and are equally puzzled why a painter of such talent was involved with a relatively minor clerk like Nebamun.

Nor do historians have any record of the original tomb’s location. The man who discovered them was a Greek grave robber called Giovanni D’Athanasi, who dug them up in Thebes, as Luxor was then known, and then passed them on, via a collector, to the British Museum. However, in 1835 D’Athanasi fell out with curators over his finder’s fee and refused to divulge the precise position of the tomb. He took his secret to the grave, dying a pauper in 1854 in Howland Street, a few minutes’ walk from the museum. Ever since, archaeologists have searched in vain for the tomb of Nebamun and any treasures that it may still contain.

PROVINCIAL PROVENANCE

The Nebamun paintings have — to say the least — a colorful history, and the task of unraveling it, and for caring for these remarkable works, has been handled by Egyptologist Richard Parkinson. He showed me the panels in November, when they were cased in wood and glass, ready for removal to their new gallery. They were stacked in a museum basement store that held other Egyptian artifacts, including a series of panels dedicated to a chief treasurer, Sobekhotep. Think of him as the 18th Dynasty’s answer to a modern-day finance minister, a politician who controlled the nation’s wealth and economic destiny. Yet the panels commemorating him are thin, lifeless and provide little feeling for the man’s life or times.

By contrast, the artwork that celebrates Nebamun’s life bursts with energy. In one panel, he stands on a papyrus skiff at the head of a hunting trip into reed-covered marshes filled with tilapia and puffer fish, Egyptian red geese, tiger butterflies, black and white wagtails and an exquisitely painted tawny cat that is helping itself to the birds being brought down by Nebamun. The cat is a product of particularly grand draftsmanship, in which stripes and dots have been delicately assembled to produce a magnificently whiskered tabby. Scales on fish, feathers on ducks and soft folds in the clothes of the Nebamun retinue have also been created this way. It is an extraordinary evocation of Egyptian life. As for Nebamun, in the hunting panel he towers over proceedings, his wife Hatshepsut beside him and their daughter at his feet. Wearing a black wig and a great collar of beads, he strikes a pose that is assured and proud, almost regal.

Yet Nebamun was really just a bean counter whose job was to ensure the wheat stores in the temple of Amun were properly controlled. So how did this civil servant acquire the services of one of the greatest painters of ancient Egypt?

“These are the greatest paintings we have from ancient Egypt,” Parkinson says. “There is nothing to touch them in any museum in the world. Yet they were created for an official too lowly to have been known by the pharaoh. It is quite extraordinary.” Parkinson does, however, have an intriguing explanation. The “Michelangelo of the Nile” who created these great tomb panels was certainly working on another project in the neighborhood of Nebamun’s tomb at the time. This building or burial complex would have been constructed, and decorated, on a far grander style for a far more important figure. Nebamun merely slipped the artist and his team some extra cash and they stole off to paint his own panels.

RIGHT TIME, RIGHT PLACE

Ironically, the artist’s main project was no doubt a finer work, but it has disappeared, looted and trashed like the vast majority of ancient Egypt’s great treasures. The Nebamun panels are the only record we have of this genius. We have therefore good reason to be grateful to Nebamun, one of life’s perennial opportunists, but an astute collector of fine art just the same.

As to their purpose, the paintings were intended to make Nebamun appear important in the afterlife. They would have covered the tomb’s upper level, while his body was interred in a chamber below ground. Friends and family would have visited the upper part of the tomb, left gifts and held feasts to commemorate Nebamun’s life. “This was where life and death merged,” says Parkinson. Thus the paintings were not buried and hidden away but established a link between the living and the dead. Hence their importance to Nebamun’s family. They were to be appreciated, leisurely, after the man’s death as reminders of his achievements.

They were certainly not created at a leisurely rate, however, as Parkinson has found in his investigations of the paintings. Once the tomb’s stone walls had been erected, they were covered in straw and Nile mud mixed together into a squishy paste. Then, when this was dry, a thin layer of white plaster was added. As that started to dry, the artist and his team began to paint, using soot from cooking pots, desert stones for red, yellow and white pigments, and ground glass for blue and green. Rushes, chewed at the end, would have acted as brushes. Squashed into the dark, narrow upper tomb, the painters would have had to work by lamplight before the plaster dried. The results are almost impressionistic in the freedom of their execution.

“I think Nebamun had all his paintings done for his tomb-chapel walls in three months,” says Parkinson. “Yet the draftsmanship was quite wonderful ... I have now spent a quarter of my life studying their handiwork.”

WINDOW INTO THE PAST

The panels’ importance to modern eyes is clear. They tell us a great deal about ancient Egypt and its everyday activities, and about differences and similarities between life then and now. “The straw crates in which geese are sold at market — you see these on just about every street corner in Cairo,” says Parkinson. “And the women’s jet-black hair and skin color are just the same as we see in Egypt today.”

However, Parkinson warns about drawing too many parallels between modern life and the scenes depicted in the panels. Objects and animals are often included because they had great symbolic importance. That great hunt scene is more than a depiction of everyday life: the birds and cat are symbols of fertility and female sexuality, and Nebamun’s expedition can also be seen as “taking possession of the cycle of creations and rebirth,” as one scholar has put it. Certainly, visitors should take care when trying to interpret the panels’ meaning.

Nevertheless, the paintings repay detailed inspection. On several of them, you can see where D’Athanasi’s grave robbers had started to crowbar a panel from a wall only to find it cracking, ready to split. They would then move on to splinter open the panel at a new spot. “Only 20 percent of the panels survived these attacks,” adds Parkinson. “Only sections that would appeal to British audiences were taken: the ones with naked dancing girls and scenes from gardens. Perfect for our taste, in short.”

One or two other fragments did end up in other museums, including several that are now kept in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. Evidence also suggests that a handful of fragments may survive elsewhere. For example, records from the Cairo Museum show that, just after the World War II, a few sections from the tomb were about to be exported from Egypt, a move that was opposed by its government — so officials had the panel pieces photographed and stored in the great vaults below the Cairo Museum. And that is where they rest today, though their precise location has been lost. All that is known is that among the tens of thousands of other ancient treasures kept in the museum’s store, the missing Nebamun panels are today gathering dust in a dark, lost corner. It is a strange fate and it invites — irresistibly — a comparison with the fictional resting place of the Ark of the Covenant, dumped in a mammoth warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark. In other words, a fantastic end for some fantastic art.

When life gives you trees, make paper. That was one of the first thoughts to cross my mind as I explored what’s now called Chung Hsing Cultural and Creative Park (中興文化創意園區, CHCCP) in Yilan County’s Wujie Township (五結). Northeast Taiwan boasts an abundance of forest resources. Yilan County is home to both Taipingshan National Forest Recreation Area (太平山國家森林遊樂區) — by far the largest reserve of its kind in the country — and Makauy Ecological Park (馬告生態園區, see “Towering trees and a tranquil lake” in the May 13, 2022 edition of this newspaper). So it was inevitable that industrial-scale paper making would

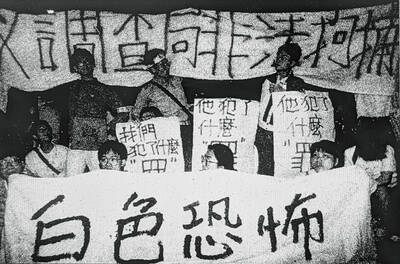

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing

Asked to define sex, most people will say it means penetration and anything else is just “foreplay,” says Kate Moyle, a psychosexual and relationship therapist, and author of The Science of Sex. “This pedestals intercourse as ‘real sex’ and other sexual acts as something done before penetration rather than as deserving credit in their own right,” she says. Lesbian, bisexual and gay people tend to have a broader definition. Sex education historically revolved around reproduction (therefore penetration), which is just one of hundreds of reasons people have sex. If you think of penetration as the sex you “should” be having, you might