Senator Barack Obama used one to announce to the world his choice of a running mate. Thousands of Americans have used them to vote for their favorite American Idol contestants. Many teenagers prefer them to actually talking.

Almost overnight, text messages have become the preferred form of communication for millions of people.

But even as industry calculations show that Americans are now using mobile phones to send or receive more text messages than phone calls, those messages are coming under increasing fire because of the danger they can pose by distracting those who send them. Though there are no official casualty statistics, there is much anecdotal evidence that the number of fatal accidents stemming from texting while driving, crossing the street or other activities is on the rise.

“The act of texting automatically removes 10 IQ points,” said Paul Saffo, a technology trend forecaster in Silicon Valley. “The truth of the matter is there are hobbies that are incompatible. You don’t want to do mushroom hunting and bird watching at the same time, and it is the same with texting and other activities. We have all seen people walk into parking meters or walk into traffic and seem startled by oncoming cars.” In the latest backlash against text messaging, the California Public Utilities Commission announced an emergency measure on Thursday temporarily banning the use of all mobile devices by anyone at the controls of a moving train.

The commission acted after federal investigators announced that they were looking at the role that a train engineer’s text messaging may have played in the country’s mostly deadly commuter rail accident in four decades.

A California state lawmaker is also seeking to ban text messaging by drivers, a step already taken by a handful of other states.

“We have had far too many tragic incidents around the country that are painful proof that this is a terrible problem,” said the legislator, state Senator Joe Simitian, who wrote the state’s hand-free cell phone law and is now pushing for the texting ban.

The fight against text messages is also reaching beyond the realm of public safety. The National Collegiate Athletic Association’s board recently upheld a 2007 ban of all text messages from coaches to student recruits. “The student athlete advisory committee believed that it was unprofessional, intrusive and expensive,” said Erik Christianson, a spokesman for NCAA.

Theaters, too, long accustomed to chiding cell-phone users and people who crumple their cough drop wrappers, have taken on texting. Aided by cell-phone service providers, parents have moved to limit the hours that their children may get and send text messages.

Text messaging — also known as short message service, or SMS — first took off in Japan, cell-phone technology experts say, because the cost of texting there was less than that of making cell-phone calls, and because the Japanese language was conducive to the practice.

In the US, the practice has accelerated greatly in just the last few years, as the technology has improved and ubiquitous devices have increased text users. In the US in June, 75 billion text messages were sent, compared with 7.2 billion in the same period just three years ago, according to the CTIA — the Wireless Association, the leading industry trade group.

The consumer research company Nielsen Mobile, which tracked 50,000 individual customer accounts in the second quarter of this year, found that Americans each sent or received 357 text messages per month then, compared with 204 phone calls. That was the second consecutive quarter in which mobile texting significantly surpassed the number of voice calls.

The lure of texting technology is self-evident. It is fast and direct, screening out the pleasantries that even standard e-mails call for, such as “how are you.” It is used to blast information among co-workers, inform parents of their children’s whereabouts and, as Kwame M. Kilpatrick demonstrated en route to his downfall as mayor of Detroit, is useful in expressing feelings of romantic desire. (Object lesson No. 2: text messages are also subject to subpoena.)

“It is just a super useful tool,” said Caitlin Williams, a bakery owner in San Francisco. Her outgoing cell-phone message encourages people to send her a text. “You can kind of cut to the chase,” Williams said. “Sometimes you just want your questions answered without having to answer a lot of questions about how your day is.”

For all her love of texting, Williams says she has seen the disadvantages as well. “Of course there is the dangerous driving while texting,” she said, “and the obnoxious person in front of you texting instead of ordering their coffee, which happened to me yesterday. We are not at a point where there are a whole lot of rules for proper etiquette for texting. I think as it becomes a more acceptable form of communication, people will regulate themselves a little more.”

Teenagers and young adults have adopted text-messaging as a second language. Americans 13 to 17 years of age sent or received an average of 1,742 text messages a month in the second quarter, according to Nielsen. And according to one survey commissioned by CTIA, four of 10 teenagers said they could text blindfolded.

Kyle Monaco, a 21-year-old student in Chester, Pa., estimated that he sends 500 text messages a month, compared with 50 phone calls. “It’s not that I don’t like to talk on the phone,” he said. “Sometimes I just want to see what’s going on, as opposed to having a conversation. So it is easier to send a text.”

Parents are often torn between their love of instant access to their children and their loathing of others’ having the same. In August, Verizon began offering a service that blocks texting during certain times of the day.

“Usage controls were developed at the request of customers,” said Jack McArtney, associate director of advertising and content standards for Verizon “We know of some people who want to keep the kid’s phone from buzzing all night. They want them to get some sleep.”

And texting at the wrong time can be extremely dangerous. Over the last two years, news accounts across the US have chronicled the death or serious injury of people who walk into traffic while texting or who drive while doing so; police officials said last year that a crash that killed five cheerleaders in New York might have been linked to texting. A recent Nationwide Insurance survey of 1,503 drivers found that almost 40 percent those respondents between the ages of 16-year-olds to 30-year-olds said they text while driving.

On Wednesday, the National Transportation Safety Board said its investigators had determined from phone records that the commuter-train engineer in last week’s disaster had sent and received text messages while at the controls during the run in which the train collided with a freight locomotive. Twenty-five people were killed in the crash, and more than 130 injured. Further, a group representing emergency room doctors issued a warning in July against texting while doing other activities, citing a rise in injuries and deaths seen in emergency rooms around the country stemming from texting.

As policymakers consider their options, use of the technology shows no sign of ebbing. Joanne Kent, who is 62, found herself flummoxed when her two granddaughters sent her text messages she did not know how to retrieve.

So Kent, a retired physician’s assistant, attended a class held by AT&T at the senior center in Wallingford, Conn. hoping someone there could show her how. “They’d send me a text saying, ‘Have papa come pick me up’ and I couldn’t open it,” she said of her granddaughters. “They finally told me, I had to learn.”

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

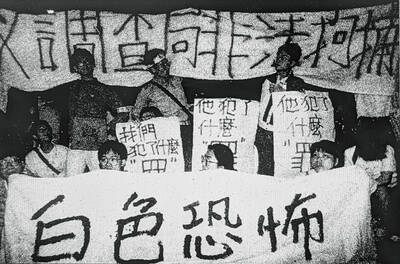

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing

When life gives you trees, make paper. That was one of the first thoughts to cross my mind as I explored what’s now called Chung Hsing Cultural and Creative Park (中興文化創意園區, CHCCP) in Yilan County’s Wujie Township (五結). Northeast Taiwan boasts an abundance of forest resources. Yilan County is home to both Taipingshan National Forest Recreation Area (太平山國家森林遊樂區) — by far the largest reserve of its kind in the country — and Makauy Ecological Park (馬告生態園區, see “Towering trees and a tranquil lake” in the May 13, 2022 edition of this newspaper). So it was inevitable that industrial-scale paper making would