Dengue fever is a Los Angeles band featuring a Cambodian-born singer and five American alt-rockers who regularly embarrass her onstage.

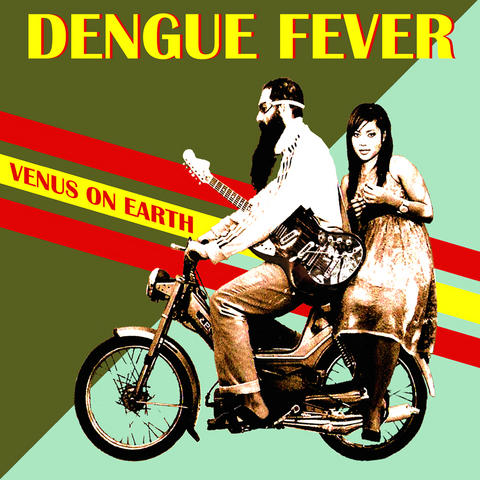

On the cover of its new album, Venus on Earth, the guitarist Zac Holtzman, with a long beard and goggles, drives a scooter with the vocalist Chhom Nimol sitting demurely behind him sidesaddle, the way a good Cambodian girl would ride through the streets of Phnom Penh. Dengue Fever, which specializes in an unlikely mix of 1960s Cambodian pop, rock and other genres, is a lot like that image. Propriety and smart aleck indie rock race by, blurring together.

It is a band of rollicking lightness that keeps coming up deep. At a recent show in the Echo Park neighborhood here, the male members were downright goofy, but Chhom, singing mostly in Khmer and dressed in shimmering Cambodian silk garments she designs herself, looked like old-school royalty, a queen before the hipoisie. No wonder she seemed to roll her eyes from time to time onstage. But after the set, when she lighted a candle onstage to honor those killed by the Khmer Rouge, her voice broke and tears ran down her face.

PHOTO COURTESY OF KEVIN ESTRADA

"I think we balance each other out," Holtzman said in a recent interview. "She'll bring the whole place to a hush, and that would be a long night if it was just that. And then we smash the place up."

Dengue Fever formed after the Farfisa organ player Ethan Holtzman, Zac's brother, traveled to Cambodia in 1997, discovered 1960s Cambodian pop and returned with a stack of cassettes. This was not the sort of roots-driven folk sounds ethnomusicologists crave; this was locally produced, gleefully garish trash infused with the surf guitar and soul arrangements that Armed Forces Radio blasted across the region during the Vietnam War. It flourished until the Khmer Rouge came to power in the 1970s and functionally dismantled Cambodian culture.

Dengue Fever's music is a tribute to that lost pop. But the six members of Dengue Fever form a quintessential Los Angeles crew, with a mix of backgrounds and interests that seems fitting in a region with the largest Cambodian population in the US (in Long Beach, south of downtown Los Angeles) and a flourishing indie rock scene (in the hills east of Hollywood). The band is the musical equivalent of that ultimate modern Los Angeles marker, the polyglot strip-mall sign. It too offers a cultural mash-up; beyond the obscure Cambodian pop you can hear psychedelia, spaghetti western guitars, the lounge groove of Ethiopian soul and Bollywood soundtracks. Seeing Hands, on the new album, has an almost Funkadelic groove, while Sober Driver is an all but emo complaint about a guy who drives the cute girl everywhere and gets nowhere.

PHOTO COURTESY OF KEVIN ESTRADA

Now Dengue Fever is starting to make its mark far from its hometown. The band recently returned from the Womex world music festival in Seville, Spain, where it was one of a handful of acts to play showcase performances. British publications have included it in "next big thing" roundups, and Dengue Fever's songs have been on television and film sound tracks, including Jim Jarmusch's Broken Flowers. A new documentary, Sleepwalking Through the Mekong, that follows the group on its first trip as a band to Cambodia, seems likely to gain it further notice.

"The underground people are getting hip to world music, and the world music side is getting hip to how you don't have to have a dreadlock wig and Guatemalan pants to be cool," said the bassist Senon Williams, sitting in his backyard with Chhom and Zac Holtzman.

"Now that Nimol is going to start singing more in English," he added, "it's making new things possible for us. Nimol really wants to connect with the American audience more now."

Dmitri Vietze, a publicist and marketer for many global music acts, sees the band as "part of a larger developmental pattern" in world music. "Can you stick them in the world-music bin at brick and mortar retail stores?" Vietze asked. "I don't know. But ... they are a part of a huge and promising future."

Older generations of Cambodians in California are sometimes critical. "They don't want me to show off too much of my dress," she said. "They always tell me, 'Don't forget you're a Cambodian girl.'" But the younger generation responds to Dengue Fever and even breakdances to its reinvention of a mongrel music that is itself a reinvention of a mongrel music from the West.

Folk music it's not, but in one crucial way Dengue Fever has folk resonances. To Chhom and other young Cambodians in the States, pop singers like Sinn Sisamouth and Ros Sereysothea, who died in a labor camp in Cambodia in the 1970s, hit a nerve that blues singers or hillbilly bands do for many Americans: the music takes listeners back home, to a home that doesn't precisely exist anymore.

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

It was just before 6am on a sunny November morning and I could hardly contain my excitement as I arrived at the wharf where I would catch the boat to one of Penghu’s most difficult-to-access islands, a trip that had been on my list for nearly a decade. Little did I know, my dream would soon be crushed. Unsure about which boat was heading to Huayu (花嶼), I found someone who appeared to be a local and asked if this was the right place to wait. “Oh, the boat to Huayu’s been canceled today,” she told me. I couldn’t believe my ears. Surely,