New York's Guggenheim Museum mounted an exhibition in 1997 titled Fashion/Art, which examined the relationship between art and fashion in the 20th century.

That exhibit revealed how certain early 20th century art movements, such as Italian Futurism and Russian Constructivism, combined fashion with art as a means of complimenting their notions of a utopian society. By the mid-century, the distance between art and fashion were narrowed as Pop art merged the two in a conscious effort to erase the distance between high and low art. Since the 1960s, various artists have sought to undermine the fashion world's pretension to elegance by drawing attention to the industry's underbelly.

Sean Hu (胡朝聖), curator of MOCA's current exhibit titled Fashion Accidentally saw the Guggenheim exhibit and was inspired by the ideas expressed in the highly regarded show.

PHOTOS: COURTESY OF MOFA, TAIPEI

"Since then I have been collecting information related to clothing to find a context for this exhibition," he said after the exhibit's opening reception.

"I want to discuss this issue through semiology, sociology, psychology and also feminism ... and ... through clothing, respond to what is going on in our world, to what is happening at this moment."

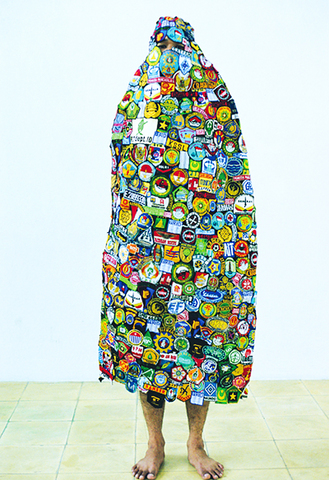

Bringing together the work of 15 young artists from around the globe whose work covers a variety of media, the show is presented thematically and employs a political and humorous visual language that makes it accessible, though with enough resonance to appeal to those well-versed in critical theory.

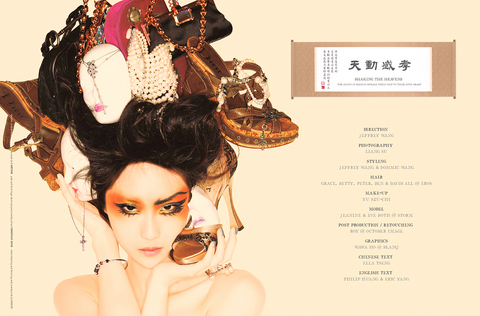

Illustrating the relationship between feminine ideals and fashion is Jeffrey Wang's (王九思) witty 24 Xiao (二 十 四孝), a series of exquisitely rendered c-print posters that appropriate the traditional Chinese concept of filial piety. Taking idealized notions of how women should look, the artist fuses each image with objects of desire. The images are both decadent and banal in their use of symbols, and the artist employs a satirical visual language that is at once low and highbrow.

The commodification of Western images and their onslaught on Asian culture is humorously portrayed by Yasumasa Morimuras' series of large photos called Self-Portrait (Actress). The Japanese artist photographed himself dressed up as famous female movie stars, which effectively demonstrates the bizarre nature of gender issues and the often unspoken cultural hegemony that this entails. The artist has deliberately left obvious flaws in the pictures.

Humanity's cruelty and disrespect for life are the themes of Nicola Costantino's Human Furrier, where skin-like fabric and human hair are used to create a fictitious line of clothing that draws attention to our obsession with satisfying cravings for clothing. Taking a different approach with her line of fashion, Taiwan-based, American artist Susan Kendzulak explores relationships between humans in her installation Love/Hate. Juxtaposing her line of conjoined knitted apparel with a boxing ring shows how love is a messy, complex and intimate affair.

E.V. Day's installation titled Chanel/Shazam explodes — literally — a garment of Chanel clothing and then suspends the cotton shrapnel from fish wire. Harking back to 1960s and 1970s feminist thought, in which clothing is intimately tied up with freedom and subjugation, Day's work menacingly illustrates the predicament still faced by today's women.

Chinese artist Sui Jian-guo's (隋建國) sculpture titled Rainbow Jacket blends Sun Yat-sen's (孫中山) drab tunic suit — often misinterpreted as those worn by Mao Tse-tung (毛澤東) — with the psychedelic cover art of the Beatles' Sergeant Pepper album, and brings to light the ways in which China is both steeped in the past and opening to Western influences.

Harking back to 1990s militant political art, though still eminently topical, is Venezuelan artist Jose Antonio Hernandez-Diez' My Fucking Jeans, one of four installations that examines the relationship between highly paid designers and the cheap overseas labor that turns the images into products — items that the laborers themselves couldn't possibly afford.

Though the show has its roots in fashion history and serious political activism, it is more than a didactic exhibition and takes a humorous look at the accidents the world of fashion continues to make.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades