Traveling in modern Vietnam, you quite often meet Americans who fought in the Vietnam War. Two separate couples I encountered last year were there to visit children they had adopted and whose education they were paying for. This was clearly something in the way of a guilt offering, attempting to alleviate a sense of wrong-doing that the Catholic Church wisely attends to through the ritual of Confession.

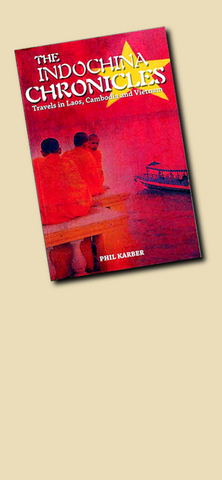

Arkansas-born writer and former businessman Phil Karber fought in the Vietnam War while still a teenager. In the late 1990s he went back, with his wife, to live in Hanoi, drawn to experience again a country first witnessed in very different circumstances. Then, in 2002, after four happy years there, he set off with an English artist friend to travel in leisurely fashion through Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. It would be a journey, he writes, "where my memories would shape my impressions, and my own aging would be juxtaposed against an area I helped devastate."

The result makes absorbing reading. But it's not a book of soul-searching or mawkish regret. Instead, it's a mixture of stylish eloquence, bar-room tales, good-natured observations, and frank horror at what was done in the name of freedom.

The tour, not surprisingly, began and ended in Hanoi. First the two men traveled up to Kunming by train, then voyaged down the Mekong through Laos and Cambodia to the Mekong Delta. There they turned back north and traveled through Vietnam back to Hanoi overland.

Anyone who knows the region will immediately be carried back there by even Karber's most casual descriptions. Sitting on a plastic stool in a Vietnamese street at night drinking home-brewed beer (bia hoi, at some NT$20 a liter), watching the city traffic, mostly two-wheeled, negotiate intersections without the benefit of traffic lights, resisting the cries of cyclo (bicycle-rickshaw) drivers as the stars shine in the pollution-free night sky — innumerable moments in this book made me catch my breath in sadness at not being there even as I turned the pages.

Karber is probably a better writer than he knows. Of Hanoi he writes, "The traffic circle dinned as the Konika and Fuji electronic billboards flashed ads like screensavers ... Postcard boys latched onto tourists one last time before vanishing for the night ... The traffic heaved and swirled into a white blur of light, like the slow-shutter exposure of a comet." He expresses gratitude to editors for pruning an "overwritten" manuscript, but my suspicion is that itchy editorial fingers may have lost us some pearls of great price in the process.

But then Karber will characteristically relapse back into jokes about "Pancakers" (backpackers — because of their perceived fondness for banana pancakes) and "Buddha Bellies" (heavy drinkers). His English painter friend, Simon Redington, at one point remarks that the duty of an artist is to live an artist's life. Perhaps Karber should have taken to heart similar advice as applied to writers, and not spent so much time in his former business pursuits where he perhaps encountered low-caliber humor a couple of times too often.

Laos and Cambodia receive more cursory treatment than Vietnam. Luang Prabang is largely seen as a former Buddhist and royal enclave, while in Phnom Penh the pair concludes that it was "unsuitable to take one's pleasures in a city that had felt so much pain."

The book's more extended references to the Vietnam War almost all adopt a Vietnamese perspective. Remembering his days at a listening post on the Thai banks of the Mekong, Karber writes of the time "... inflicting mass carnage was known as pacification; the military invasion and occupation of another country was called liberation; and search-and-destroy really meant destroy-and-search. This reverse speak, coupled with the deceptions of the secret war, were tell-tale signs of a wider condition ... ."

A typical chapter is entitled May 5, 1968 and refers to a day of savage fighting in which a friend and fellow American resident in modern Vietnam, John Lancaster, lost the use of his lower body. Lancaster joins the duo in his wheelchair at Danang, and after a long description of the day's events 34 years before, the question arises as to whether the Vietnamese soldier who shot him survived. Lancaster, who now works for the legal rights of Vietnam's possibly 10 million disabled, replies "I feel certain he got wasted. They [marines] blasted the whole area once he showed himself. But maybe not. I hope like hell he made it."

This is not the Vietnam experienced by today's many young travelers, for whom the war is past history. To them the beaches of Mui Ne and Nha Trang, and the old cities of Hue and Hoi An, feature highest on the agenda. Such a perspective is not available to Karber, however, who has other, often very disturbing, memories.

Even so, the book is surprisingly upbeat in tone. It ends with an excursion on Russian "Minsk" motorbikes (much in evidence in Vietnam's northern hills) to Pac Bo near the Chinese border where Ho Chi Minh lived in hiding for a time. It was an "Arcadian communist beachhead," Karber concludes, and his group of expatriate bikers respectfully (but also jovially) lunch there on salami, processed cheese, baguettes and a bottle of French wine.

One omission from this otherwise excellent book is any extensive account of Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City). It's common enough to hear it denigrated in comparison with Hanoi, but for me this lively metropolis on which the French lavished so much love is the nicest city in Asia. It's really surprising that Karber finds it worth only a few casual and dismissive sentences. But perhaps if you're a Hanoi resident, decrying the bigger and richer Saigon is something that's done as a nightly ritual over the deceptively potent bia hoi.

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,