Fast fashion may be moving too fast for customers to keep up.

What started with inexpensive Isaac Mizrahi trench coats and Cynthia Rowley bedspreads at Target stores, and drew crowds to H&M with cheap versions of Karl Lagerfeld and Stella McCartney fashions, has evolved into a frenzy for budget clothes by designers of even questionable celebrity: Sophia Kokosalaki has a deal with Nine West, and Roland Mouret with Gap. Not to mention the Viktor & Rolf clothes introduced recently at H&M.

Those are not exactly household names. But they are veritable fashion stars next to the designers hired to prolong the buzz around the opening of a mammoth New York flagship in SoHo for the Japanese retailer Uniqlo, whose arrival could further reshape the American clothing industry with its promise of high-quality cashmere sweaters for US$99 or less.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Uniqlo will be the largest single-brand fashion store in the retail-saturated Manhattan neighborhood, putting its competitors on notice that the company has aggressive plans for the US.

Uniqlo, which has blanketed Japan with inexpensive sportswear sold in 720 stores, is making an expensive bet that American consumers have not already overdosed on the "cheap chic" designs intended to bring a sense of style to retailers from Kohl's to Wal-Mart.

The store's democratically priced basics will include designs by a rotating assortment of global talents, some rising stars of New York fashion, like Alice Roi, Alexander Plokhov and Phillip Lim, and others who are little known outside of Japan, like Halb, Kino and G.V.G.V.

You've heard of those, right?

But the fast-fashion strategy already shows signs of wear and tear, most notably at Wal-Mart, which was disappointed by reaction to its introduction of more fashionable women's clothes this year, including its version of a fast-fashion line by the designer Mark Eisen.

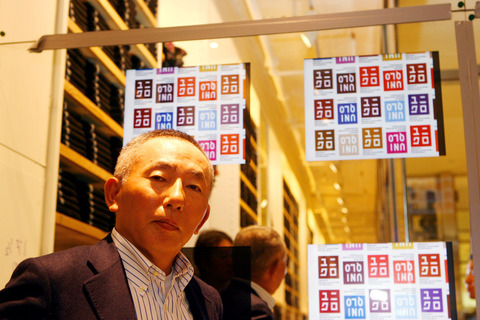

Speaking through a translator, Tadashi Yanai, who founded Uniqlo with a single store in Hiroshima in 1984, said the splashy entrance into the US — subway ads, taxi tops and temporary stores have become ubiquitous in Manhattan in the last year — was conceived to make people take seriously a retailer that has most often been described as the Gap of Japan.

"If I opened a very small store, no one would ever pay attention," Yanai said. "We want to sell basics to everyone, so to make people notice us we have to open in a big way, to make people recognize who we are."

If anything, Uniqlo is arriving late to the party, and treading on ground that will seem familiar on this particular stretch of Broadway in SoHo, where there is already a Zara, an H&M and a Banana Republic.

With its soaring architecture and raw, warehouselike space, the new 3,344.5m2 Uniqlo store looks much like the Bloomingdale's that opened at 504 Broadway in April 2004. In place of main-floor cosmetics counters, the entrance is dominated by an interior glass display filled with revolving mannequins and clean, linear displays of cashmere sweaters, some 7,680 of them, folded in repeating floor-to-ceiling grids.

Yanai predicted the chain's sales in the US would reach US$30 million by next year — a figure that includes revenue from the SoHo store and temporary outlets built around the region over the last two years.

He expects Uniqlo to become profitable in the US in its second year, but that could prove challenging, given the expensive lease the company signed and its high-priced marketing blitz across the city. It took Zara and H&M three to five years to turn a profit.

The company projected that Uniqlo's sales would nearly triple to US$9 billion by 2010, up from US$3.3 billion in 2005, making the chain one of the world's biggest apparel retailers. (Becoming No.1 will take work: Gap has sales of US$16 billion.)

As part of its battle plan, the company has told Wall Street analysts it is eager to make an acquisition outside of Japan — and has US$4 billion to spend. But Wall Street is not sure what to make of Uniqlo.

Gabrielle Kivitz, a retail analyst at Deutsch Bank Securities, said the clothing she had seen so far was "very, very basic — unusually basic." When she met with Uniqlo executives last year, the company's message "was Banana Republic quality at Gap or Old Navy prices."

"It had me a little concerned," she said. "In this market, that will not fly."

The basics apparel business, she said, is cutthroat, crammed with discount chains selling the same button-down shirts, skinny jeans and fur-trimmed puffer jackets at roughly the same price.

Yanai has long bristled at descriptions of Uniqlo as a Japanese version of any competitor, from Zara to Old Navy. The difference, he said repeatedly, is that Uniqlo sells "very high-quality basics with a little bit of fashion."

But the company has faced some language barriers in conveying that message to American consumers. Last September, the company began opening stores in New Jersey and a temporary location on Greene Street in Manhattan to introduce its designs during the holiday shopping season.

"We tried to imitate the Japanese model as much as possible," said Nobuo Domae, chief executive of Uniqlo USA. "And that was not very good. We used metal shelving that was very efficient and functional, but we didn't know that was only used for discounters. People might have thought our product was like Wal-Mart."

That may explain why the company has opened such a lavish store in SoHo, rather than, say, amid the shopping malls of New Jersey.

"People in SoHo are more open to new things, but customers in New Jersey are more conservative," he said. "It's easier to communicate new things here."

At times, the fashion can be hard to find in the basics at Uniqlo. Asked about the khakis at the store, which look very much like khakis at Gap and J. Crew, Yanai yanked a pair off the wall and placed his index finger on a small set of stitches along the cuffs.

"See, it's different," he said.

In a typical winter season, Uniqlo sells 1 million cashmere sweaters, which retail for US$89 to US$99 but are frequently on a promotional half-price sale. They are silky soft, but the differences from those sold in other stores are not readily apparent.

A new sweater style this year bears a 15cm zipper at the neck with a leather pull, a style originated by Hermes (for four figures) and popularized by J. Crew last year (for about US$200).

“Ours is half the price," Yanai said.

The focus on basics, rather than on fashion, contrasts sharply with that of Zara and H&M, which introduced cheap chic to the US.

Yanai said the two chains "copy fashions from the runway and get it out into the stores as soon as possible. That is not what we do." The typical American consumer does not need or want runway fashions, he said. "They might find it difficult to wear."

Even the designers Uniqlo has hired must work within the narrowly drawn parameters of Uniqlo's basic merchandise. The most extravagant design in the store is a white leather motorcycle jacket for US$299.

Attracting big name -- or even not-so-big name -- designers has proved effective for the image of American retailers. But its value to consumers is less clear, and likely to diminish, as stores dig deeper into the designer gene pool.

In interviews outside Uniqlo's temporary store in SoHo, some shoppers said they bought bargain fashions based on style and quality, rather than the reputation of a designer.

Francine Hunter McGivern, a 56-year-old Manhattan real estate broker, has stopped shopping at H&M because, she said, "the quality diminished since it opened."

But the sweaters she bought at Uniqlo's temporary stores have survived a year's worth of washing and drying. "I am already a loyal customer," she said. "It's high quality for the price."

But is it fashion?

"Not to me," she said. "I pay a lot for fashion. I am not looking for a bargain. You put this in your wardrobe to mix and match with the rest of your clothes."

JuJean Tran, 23, purchased a butterfly-patterned T-shirt for US$15.50 from a booth set up on the sidewalk outside the SoHo construction site.

"Nobody ever knows who is behind these big brands," she said. "Who cares, if it's cute?"

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

It was just before 6am on a sunny November morning and I could hardly contain my excitement as I arrived at the wharf where I would catch the boat to one of Penghu’s most difficult-to-access islands, a trip that had been on my list for nearly a decade. Little did I know, my dream would soon be crushed. Unsure about which boat was heading to Huayu (花嶼), I found someone who appeared to be a local and asked if this was the right place to wait. “Oh, the boat to Huayu’s been canceled today,” she told me. I couldn’t believe my ears. Surely,