"My speciality is predicting the future," declared Matt Black, the louder, more opinionated half of Coldcut. "The world's about to become a lot more dangerous. The choices that we and our children are going to have to make about things like cloning are going to become more and more difficult. People have no idea. They think it's science fiction." He shook his head with the spiny, impatient intelligence of Richard Dawkins. "I'm actually going to get a sample of my DNA taken as soon as possible and frozen so I can be cloned again in 1,500 years time. I quite fancy living for ever."

Further down the sofa, his bandmate Jonathan More vehemently shook his head in a manner that suggested he has heard this idea before and doesn't like it one bit. "A cardboard box at the end of the garden for me," he said.

Like all the best duos, Coldcut is an odd couple. Black, the younger by four years, is a former computer programmer with a degree in biochemistry. In his long black coat, wide-brimmed hat and rakish scarf he would make an excellent, slightly intimidating Doctor Who.

More, an erstwhile art teacher, has the wardrobe of a country gent and a fondness for amiable, rambling metaphors. "Coldcut's a reasonably good vehicle," he pondered. "I might pop out for the odd walk about from time to time, explore the lay-bys, but I don't need to get another vehicle."

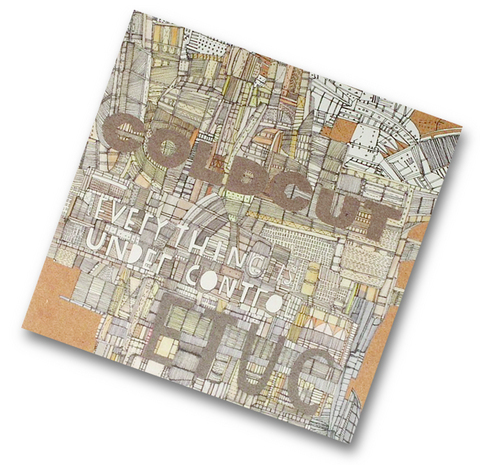

British dance music's most dogged survivors met over the counter of the niche retail outlet Reckless Records in London in 1986: More was working there. Black brought in a tape he was making for a competition for London's Capital Radio, and the resulting track, Say Kids, What Time Is It?, became their first single. They were briefly Top of the Pops regulars, manning the samplers behind Yazz and Lisa Stansfield and popularizing sample-based music. Their radical cut-up of Eric B and Rakim's Paid in Full was a landmark remix and their 1996 Journeys By DJ compi-lation remains the standard by which all DJ mix albums are judged. More recently, they have developed audiovisual mixing software such as VJamm. Considering all the mix albums, remixes, soundtracks, collaborations and art projects, it's not surprising that their new album, Sound Mirrors, is only their fourth.

"What's good about being Coldcut is we don't have to be part of the normal music-business sausage machine," Black said. "Album, tour, album, tour, greatest hits, die. This is our 19th year in the business, which, in dance music, is an eternity."

Black and More are installed in a room above the bustling offices of their record label, Ninja Tune, whose walls are papered with posters advertising such signings as Mr. Scruff and Roots Manuva.

Their old nerve center by the river Thames, they glumly reported, now houses luxury maisonettes and a branch of Starbucks. And there have been other sea changes in Coldcut's world in the past few years. When they released their last album, 1997's Let Us Play, Black was prone to saying things like, "It's not that we're brilliant, it's just that everyone else is crap," and comparing the fuss over superstar DJs to honoring "the best hamburger griller in McDonald's." In retrospect, he wasn't far wrong as 1997 was the end of dance music's imperial phase, that period when fantastic new ideas seemed to bloom every week. It has never been as culturally relevant since.

More has a metaphor for it. "When I was at art college I learned about Picasso but I didn't appreciate his work at the time because he'd been photocopied so many times that the quality degraded from his beautiful painting to a couple of licks of paint on a shit, made-in-Thailand piece of junk. That's what happens with a lot of different things. It starts, it's interesting, lots more people get on board, it gets exciting and then it all goes wrong."

PHOTO COURTESY OF COLDCUT

Black, typically, prefers a scientific diagnosis. "I think it ran out of bpm (beats per minute). The range of dance music is 60bpm to 200bpm, which is pretty much the range of the human heartbeat. After 200bpm your heart blows up. It's like in fashion -- the length of skirts from the microskirt to the one that trails a few meters behind you. There aren't going to be any more innovations in skirt length."

Electronic music will be vital again, Coldcut said, when another generation discovers and reinterprets it. Until then, Black and More have decided that the way forward is songs. In the early 1990s they turned to abstract instrumentals, pioneering the sound that they playfully dubbed "funkjazztical tricknology" and everybody else called trip-hop. Now that music-making software has become so accessible, the challenge has gone out of it. Hence Sound Mirrors' ambitiously expansive remit -- bellicose rap-rock, frazzled electro-blues, paranoid rave -- and myriad vocalists, including Roots Manuva and Soweto Kinch.

"Check It Out Now the Funk Soul Brother was never going to compete with Honky Tonk Woman," said Black. "For a moment, yes, but not long-term. You will come back to songs that you can sing." He has a formula. "When you're bringing things to people, 60 percent that they can deal with and 40 percent new is about the right ratio."

Coldcut is nothing if not adaptable. Black and More became British dance music's first pop stars back when nobody was making much money out of it. Black lost his place on a government employment scheme when he missed a meeting to appear on Top of the Pops. When their major-label deal went sour, they founded the below-the-radar Ninja Tune, inspired by their trips to Japan.

"Our manager Jazz Summers said to me that we'd never make a record as good as People Hold On (with Lisa Stansfield)," More said.

"And I think we have. I've always kept that as a guiding force: the ninja art of turning around things like that and using it as an energy to drive you." That attitude produced their much-admired club night Stealth and the Journeys By DJ album. "We thought, `Right, we'll fucking show them,''' Black recalled. "And we did."

In the years between albums they have had, as Black put it, "many pies in the oven." They're surely the only act in the world whose collaborators include Steve Reich, Radiohead, Hari Kunzru and the British Antarctic Survey. For the 2001 election, they produced an audiovisual cut-up of political footage called Revolution. Three years later, they posted samples on an activist Web site and invited members of the public to help make a US equivalent. "I've got Mrs. Thatcher to thank for politicizing me," beamed More, who has a collection of 1980s protest memorabilia and grows misty-eyed at the mention of important industrial disputes of the day.

I wonder if they ever feel nostalgic for the unbottled excitement and dizzying potential of dance music's infancy. More does, a little, but Black is resolute. "I don't. I'm not losing my edge at all. I'm more able, capable and happier right now and I still feel we can do our best work. We're not running out of ideas. Time," he conceded with a grin, "we might run out of."

Ah, but then there's always cloning.

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,