Me and You and Everyone We Know, winner of prizes in Cannes and at Sundance, is Miranda July's first feature film, and its wide-eyed, quizzical approach to the world can seem almost naive. But this guilelessness -- which will either charm you or drive you up the wall -- is more a calculated effect than the simple expression of a whimsical sensibility.

Before turning to film, July was a conceptual artist (working in video and other media), a pursuit that demands dogged self-confidence, as well as a willingness to look at even the most trivial objects and events as potential material for aesthetic transformation. Though her movie has a clear narrative line, and might even be classified as romantic comedy, it is also a meticulously constructed visual artifact, diffidently introducing the playful, rebus-like qualities of installation art to the conventions of narrative cinema.

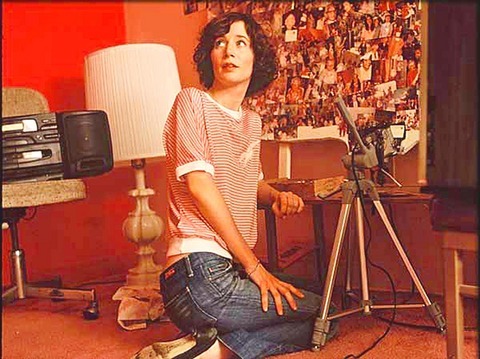

It is a meeting as tentative, and in the end as affecting, as the wistful, start-and-stop romance pursued by a conceptual artist named Christine (July) and a shoe salesman named Richard (John Hawkes).

PHOTOS COURTESY OF FOX MOVIES

Richard, newly separated from his wife, has occasional custody of his two sons, who regard their father with a mixture of curiosity and alarm, as if he were a new arrival from outer space or an escapee from the insane asylum. To be fair, he does seem a little unbalanced: one of his first actions in the film is to light one of his hands on fire, which he thinks the boys will understand as a ritual gesture consecrating the end of his marriage rather than as evidence of their mother's good sense in wanting him out of the house.

Meanwhile, Christine is preparing a videotape portfolio of her work and supporting herself by chauffeuring elderly citizens on their daily errands. She and Richard are nodal points in a web of odd, lost souls who slowly, by the film's end, form a sympathetic, eccentric circle. True to her movie's title, July proposes a delicate, beguiling idea of community and advances it in full awareness of the peculiar obstacles that modern life presents.

One of these is the tendency of city dwellers -- the movie takes place mainly in the flat, drab inland neighborhoods of Los Angeles -- to live hermetically sealed inside their own minds and habits. Individuality itself makes communication difficult, but the drive to be yourself does not dispel the longing to find (and maybe also to become) somebody else.

This longing is addressed in various ways, some of them touching, some funny, some borderline creepy. Richard's younger son, Robby (the adorable Brandon Ratcliff), who is six, wanders into an Internet romance in which his childishness is taken for a daring and sophisticated sexual kink. His older brother, Peter (Miles Thompson), a bored-looking adolescent, is first teased and then sexually initiated by two girls who hang around the neighborhood carrying on a risky flirtation with Richard's co-worker, who posts salacious notes in the window of his apartment.

Peter's affections, however, seem to be stirred by his younger neighbor Sylvie (Carlie Westerman), who is determinedly -- you might say obsessive-compulsively -- collecting linens and household appliances for her trousseau.

July observes the odd behavior of all these people, and records her own, with a warm collector's eye.

Me, You and Everyone We Know is resolutely small-scaled and observational, picking out odd details and savoring tiny jokes. But it also carries a surprisingly strong emotional undercurrent. Hawke's thin, crooked face and worried blue eyes register just how lost Richard has become, and Christine, who at first seems both appealingly nerdy and a little passive-aggressive, shares with July a deftly camouflaged determination to get what she wants.

In the character's case, this is love and a measure of recognition; in the filmmaker's case, well, perhaps the same. Everyone we know may not respond to her flirtation, which manages to be both brazen and coy. Her provocations may strike some people as overly cute and her self-consciousness as a tiresome form of solipsism. But Me and You and Everyone We Know is brave enough to risk this rejection, and generous enough not to deserve it. I like it very much and I hope you will, too.

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

When life gives you trees, make paper. That was one of the first thoughts to cross my mind as I explored what’s now called Chung Hsing Cultural and Creative Park (中興文化創意園區, CHCCP) in Yilan County’s Wujie Township (五結). Northeast Taiwan boasts an abundance of forest resources. Yilan County is home to both Taipingshan National Forest Recreation Area (太平山國家森林遊樂區) — by far the largest reserve of its kind in the country — and Makauy Ecological Park (馬告生態園區, see “Towering trees and a tranquil lake” in the May 13, 2022 edition of this newspaper). So it was inevitable that industrial-scale paper making would

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing