One of the effects of the 911 attacks was to wake up the distracted Western public to the horror of Taliban rule in Afghanistan. Now, with the Taliban out of power, Osama, the first film produced in Afghanistan since they took over in 1996, arrives to nudge us back into a state of alertness, and also, as remnants of the ousted regime continue to menace that nation's peace and stability, to trouble our sleep and our consciences as well.

Written and directed by Siddiq Barmak, an Afghan filmmaker trained in Moscow in the 1980s and clearly influenced by the Iranian humanist cinema of the 1990s, Osama begins with an apt epigraph from Nelson Mandela: "I can forgive, but I cannot forget."

Barmak is unsparing in his anatomy of the Taliban's cruelty, especially as it was directed against women, but there is very little feeling of vengefulness or hatred in the film, which makes it all the more devastating in the end.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF CROWN FILMS

The opening scenes, a kind of trompe l'oeil documentary within the movie whose meaning becomes clear only much later, capture the violent suppression of a women's-rights demonstration in the sandy, war-blasted streets of Kabul. A scared young girl (Marina Golbahari) watches from a doorway as Taliban soldiers, using water hoses, live ammunition and grenade launchers, scatter a crowd of women in blue and ocher burkhas.

This is only the most brutal and public manifestation of the pervasive terror under which women in Kabul must live. The hospital where the girl's mother works is raided, and the mother (Zubaida Sahar) is saved from arrest only when a man whose father is in her care says he is her husband. There is an almost absurd sadism to the Taliban's regulations of women's behavior. Even when a household includes no men -- hardly uncommon after so many years of war -- the women still may not be seen in public or earn a living. An uncovered foot or an unwelcome word can lead to harassment, or even severe

punishment.

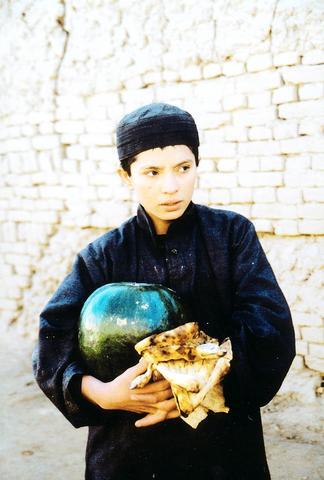

Despite all this injustice, the girl's kindly grandmother insists that the sufferings of men and women are equal because the sexes themselves are equal. This leads her to conclude that they may also be interchangeable, and so her granddaughter, with a short haircut and a dark skullcap, is sent out to work for a sympathetic shopkeeper. (She is later given the name Osama by a young beggar who knows the secret of her identity.) A similar masquerade was at the heart of Majid Majidi's film Baran, about an Afghan refugee in Tehran who disguised herself as a boy to work at a construction site.

Like Majidi, Barmak has a gently poetic visual sense: after her metamorphosis, one of the girl's severed braids is planted in a flower pot and watered by an intravenous drip her mother rescued from the shut-down hospital. He is also able to find moments of tenderness and humor in his bleak story. One sequence that stands out is a lesson in intimate hygiene taught to madrasa students by an elderly mullah -- a glimpse at the radical Islamist approach to sex education.

Barmak's patron was the Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, whose Kandahar is set in Taliban-era Afghanistan and whose daughter Samira's At Five O'Clock in the Afternoon takes place in Kabul after the American-led rout of the Taliban. Some of the surrealist touches in Osama -- gorgeous, haunting images that call for an adjective like Makhmalbafian -- may be a result of this association, and the orange glow that suffuses the landscape in all three movies may owe something to the fact that they share the gifted cinematographer Ebrahim Ghafuri. This is not to take anything away from Barmak, who had the self-confidence to embark on this project with donated equipment, a tiny budget and a cast of nonprofessionals recruited from the streets of Kabul.

The mere existence of the movie, which received the Camera d'Or special mention for best first feature in Cannes last year and the Golden Globe for best foreign film last month, would be impressive enough. But the movie's power and coherence are such that you forget completely about the hard circumstances of its making, which is nothing short of astonishing.

There is not much overt or explicit violence in Osama, which opens today in Taiwan, but an unshakable dread shadows the bright alleyways of Kabul and seeps through the heavy wooden doors of the houses. Like The Pianist, Roman Polanski's tour of Nazi-occupied Warsaw, Osama is a meticulous and beautifully made inquiry into the ways that ideological evil can infect, and ultimately destroy, the intimacies and small pleasures of daily life.

Osama has no special resiliency or survival skills; her face is, at every moment, a study in suppressed panic and worried passivity. Her unvarnished vulnerability, along with the director's combination of tough-mindedness and lyricism, prevents the movie from becoming at all sentimental; instead, it is beautiful, thoughtful and almost unbearably sad.

When life gives you trees, make paper. That was one of the first thoughts to cross my mind as I explored what’s now called Chung Hsing Cultural and Creative Park (中興文化創意園區, CHCCP) in Yilan County’s Wujie Township (五結). Northeast Taiwan boasts an abundance of forest resources. Yilan County is home to both Taipingshan National Forest Recreation Area (太平山國家森林遊樂區) — by far the largest reserve of its kind in the country — and Makauy Ecological Park (馬告生態園區, see “Towering trees and a tranquil lake” in the May 13, 2022 edition of this newspaper). So it was inevitable that industrial-scale paper making would

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing

Asked to define sex, most people will say it means penetration and anything else is just “foreplay,” says Kate Moyle, a psychosexual and relationship therapist, and author of The Science of Sex. “This pedestals intercourse as ‘real sex’ and other sexual acts as something done before penetration rather than as deserving credit in their own right,” she says. Lesbian, bisexual and gay people tend to have a broader definition. Sex education historically revolved around reproduction (therefore penetration), which is just one of hundreds of reasons people have sex. If you think of penetration as the sex you “should” be having, you might