Love them or loathe them, with the Mid-Autumn Festival only six days away mooncakes are everywhere. Be it at the local mom and pop corner store, the 7-11 or the glitzy new European supermarket, the sights and smells of the round pastry covered cakes are impossible to avoid.

Traditionally filled with red or green bean paste and now crammed with every conceivable form of filler from kiwi to egg custard, the mooncake has come a long way since the first one rolled out of the oven of an enterprising revolutionary by the name of Chu Yuan-chang (朱元璋) during the Yuan Dynasty (1279 to 1368).

Looking for a way to incite the Han people into revolt against the much-despised Mongols without alerting them, Chu, with the help of his confidant, Liu po-wen (劉伯溫), circulated a rumor that a plague was ravaging the land. The only way to prevent a disaster was to eat special mooncakes that were distributed by Chu and his fellow revolutionaries.

PHOTO: GAVIN PHIPPS, TAIPEI TIMES

Distributed solely to Han people, on the outside the cakes looked normal enough. Inside, however, lay a message giving to the day on which the anti-Yuan insurrection was to begin.

Reading "revolt on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month" the date has since become one of the most important holidays in the Chinese calendar, second only to the Lunar New Year itself.

While mooncakes are no longer used to incite rebellion -- nowadays they represent family unity and perfection -- there has been a revolution in the way in which they are manufactured and packaged.

PHOTO: GAVIN PHIPPS, TAIPEI TIMES

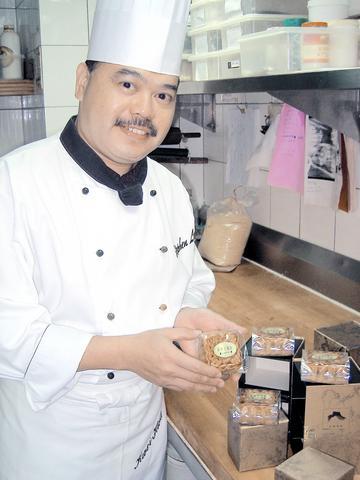

"When I was growing up in Hong Kong there were only a couple of varieties of mooncake. You had the choice of red bean, green bean or lotus paste," said Stephen Lo (盧偉強), an executive chef at Taipei's Imperial Hotel. "And they came in a simple cardboard box."

Traditional Cantonese, Taiwanese and Soochow-style mooncakes with their bean paste and egg yoke fillings continue to be popular with older generations, but over the past decade bakers have been forced to forgo tradition and move with the times.

Constantly searching for inventive ways to interest a younger generation more in-tune with Western foodstuffs than their parents, bakers now stuff their crusty pies with some highly unusual fillers.

PHOTO: GAVIN PHIPPS, TAIPEI TIMES

"If I'd made a kiwi mooncake in Hong Kong as recently as 10 years ago I would have been laughed out of the kitchen," said the chef. "Now I'm forced to come up with new and inventive fillings every year."

Some of the more popular flavorsome additions to the mid-Autumn treat in recent years have included ice cream, egg custard, ginseng, rose, green tea as well as kiwi and XO brandy. Due to current trends in juice bars, this year has seen a rise in the number of vegetable mooncakes, with both tomato and carrot paste flavors leading the way.

While tomato mooncakes are proving a hit not all "fashionable" additions to the ever-increasing list of mooncake flavors have fared so well. Some have surprisingly fallen flat with the mooncake buying public.

PHOTO: GAVIN PHIPPS, TAIPEI TIMES

"We made coffee and chocolate mooncakes a couple of years ago and we expected them to prove pretty popular, with Taiwan's fascination with coffee shops being at an all time high," said Eddie Liu (劉冠麟), assistant director of food and beverage at the Far Eastern Plaza Hotel. "Neither flavor worked, however, and we won't be using either of them ever again."

Coffee and chocolate may have proven disastrous, but some of the more outlandish flavors now available have proven surprisingly popular, especially to those with money to burn. Sharks fin, birds' nest and abalone-flavored mooncakes can only be found at only a handful of the 200 mooncake stores in Taipei, yet all three flavors sell well regardless of price.

The costliest of these varieties is abalone, one kilo of which will set you back roughly NT$40,000. According to Lo, however, the use of such ingredients and paying such vast amounts for such mooncakes is quite absurd.

"It's a bit of joke really. Birds nest and sharks fin are both tasteless ingredients unless prepared in a soup with a rich stock. And abalone, well, that's just stupid," Lo said. "People simply buy them because they are expensive items. It's certainly not for the taste."

Toying with mooncake fillers may now be readily accepted by chefs, but there has been heated debate about the issue. While chefs such as Lo tolerate the use of fashionable fillers, mention adding egg or butter to the traditional oil, flour and water based pastry and you'll rouse his ire.

"I know a lot people have taken to experimenting with more Westernized pastries, but it shouldn't be done," Lo said. "It's mooncake season, not pastry season!"

Along with the changes in mooncake production, packaging has become as important, if not more important than the cakes themselves. Manufacturers now work on the premise that mooncake boxes have to be more than simply a form of packaging.

"Customers now like to purchase something that has other uses. A box that is simply a box is not something you'd want to keep," Lo said. "Packaging that has other uses means that it will not be tossed out with the garbage as soon as the cakes have been eaten."

The multi-purpose packaging Lo's hotel has opted for this year has four mooncake-sized drawers and resembles a jewelry or kick-knack box. The nation's most popular packaging designs, however, continue to be those made of metal/tin or wood.

Although not available in Taiwan, the most outlandish design this year has been produced by a hotel in Shanghai. Designed to look like an old fashioned music box and play a tune when opened, the special packaging costs NT$2,500 -- without the mooncakes.

"It's a question of face sometimes rather than what is inside," said Liu. "I mean, even if the person doesn't particularly like the mooncakes, they can't fail to impressed by a swanky box."

This is something that this reporter discovered to be true when, on taking home a fancy box filled with traditional mooncakes, I was not thanked for the cakes themselves, but instead was asked, "Can I take them [mooncakes] out and have the box?"

In Taiwan there are two economies: the shiny high tech export economy epitomized by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) and its outsized effect on global supply chains, and the domestic economy, driven by construction and powered by flows of gravel, sand and government contracts. The latter supports the former: we can have an economy without TSMC, but we can’t have one without construction. The labor shortage has heavily impacted public construction in Taiwan. For example, the first phase of the MRT Wanda Line in Taipei, originally slated for next year, has been pushed back to 2027. The government

July 22 to July 28 The Love River’s (愛河) four-decade run as the host of Kaohsiung’s annual dragon boat races came to an abrupt end in 1971 — the once pristine waterway had become too polluted. The 1970 event was infamous for the putrid stench permeating the air, exacerbated by contestants splashing water and sludge onto the shore and even the onlookers. The relocation of the festivities officially marked the “death” of the river, whose condition had rapidly deteriorated during the previous decade. The myriad factories upstream were only partly to blame; as Kaohsiung’s population boomed in the 1960s, all household

Allegations of corruption against three heavyweight politicians from the three major parties are big in the news now. On Wednesday, prosecutors indicted Hsinchu County Commissioner Yang Wen-ke (楊文科) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), a judgment is expected this week in the case involving Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and former deputy premier and Taoyuan Mayor Cheng Wen-tsan (鄭文燦) of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is being held incommunicado in prison. Unlike the other two cases, Cheng’s case has generated considerable speculation, rumors, suspicions and conspiracy theories from both the pan-blue and pan-green camps.

Stepping inside Waley Art (水谷藝術) in Taipei’s historic Wanhua District (萬華區) one leaves the motorcycle growl and air-conditioner purr of the street and enters a very different sonic realm. Speakers hiss, machines whir and objects chime from all five floors of the shophouse-turned- contemporary art gallery (including the basement). “It’s a bit of a metaphor, the stacking of gallery floors is like the layering of sounds,” observes Australian conceptual artist Samuel Beilby, whose audio installation HZ & Machinic Paragenesis occupies the ground floor of the gallery space. He’s not wrong. Put ‘em in a Box (我們把它都裝在一個盒子裡), which runs until Aug. 18, invites