Seahorses are their own worst enemy.

Fished to the point of extinction for the traditional Chinese medicine market, they mate for life and their unwillingness to seek new partners after being separated has done little to improve their chances of survival.

One of their better hopes for conservation may lie in the unlikeliest of places -- a ramshackle shed perched on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Seahorse Ireland says its goal is to help save the species by cultivating seahorses born in captivity for the growing aquarium market.

"We want to make people aware that the captive-bred seahorse is a much better buy," said production manager Ken Maher, from the makeshift laboratory in Connemara, west Ireland.

"There's no deleterious effect on the environment and the seahorse will survive and flourish in your tank."

PHOTO: REUTERS

Seahorses are no ordinary sea creatures, notwithstanding their monogamy which is highly unusual for the animal kingdom. It is the male who receives eggs from his female partner and fertilizes them himself.

"The female swims up to her chosen male partner and the two change color as they dance around each other for hours in an elaborate courtship ritual," said Maher.

After receiving eggs from the female and fertilizing them himself, the male is pregnant for about three weeks before giving birth.

Captive-bred

The low-cost technology pioneered by Seahorse Ireland could be transferred to poorer parts of the world where seahorse stocks are fast becoming depleted.

Next year, a ban on international trade in seahorses, unless they are captive-bred or for scientific purposes, is due to come into operation, a move likely to cripple the livelihoods of thousands of dependent fishermen.

"Other conservation bodies try to say `this is a sanctuary, no fishing is allowed here,' and try to get locals to make arts and crafts instead," Maher said.

"But these people are fishermen who want to live near the sea. I know I could not switch to making arts and crafts if I was in their position."

If no alternative was provided, the trade would simply go underground, Maher said.

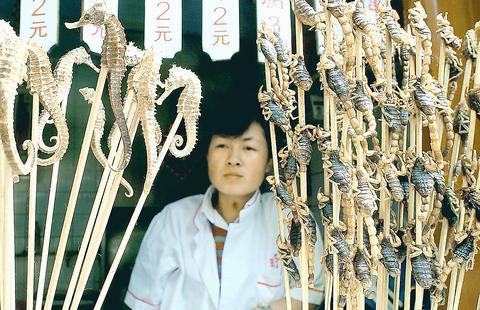

An estimated 40 million seahorses a year are taken from the wild for traditional Chinese medicine in which they are used as an aphrodisiac as well as a range of ailments including heart disease.

Demand has risen in recent years to such an extent that seahorses retail for about US$1,900 a kilogram in Asia, almost the price of gold.

A further one million are fished for the curio trade because seahorses retain their shape and color when dried.

The pet trade takes another one million, but very few survive beyond a few months or so without live food.

Frozen food

That's where Seahorse Ireland comes in -- it trains captive-born seahorses to get used to frozen food.

"Once we train them to take frozen food, they can be sent all over the world," said Maher.

Set up three years ago by Maher and his fellow marine biologist Kealan Doyle, Seahorse Ireland has two key advantages right on its doorstep.

First, the larger of the two seahorse species local to Ireland, the spiny seahorse, can be found in seagrass beds in and around nearby Kilkieran Bay.

In addition, the west coast of Ireland offers an abundance of zooplankton enriched by nutrients from the Gulf Stream, and the company has developed a system to extract and freeze this food.

Maher dismissed criticism from some environmentalists that breeding seahorses in captivity will serve only to boost demand, heaping more pressure on rapidly-declining stocks.

Capable of spawning 200 offspring at a go in the wild, with the right conditioning seahorses could breed closer to 1,000 juveniles, Maher said.

The company aims to sell seahorses for the pet market, retailing from 200 euros each, over the Internet, to be dispatched for next-day delivery.

"Seahorses travel quite well in tightly packed bags, with oxygen, just like goldfish," Maher said.

Sales are forecast at around 30,000 next year and around 70,000 the year after. Over time, Maher said there were plans to open a visitor center, using the seahorse as an icon for other endangered species.

"We will use it as a focus for conservation because it's not just the panda in China or the river dolphin in India that are in need of help," he said.

In Taiwan there are two economies: the shiny high tech export economy epitomized by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) and its outsized effect on global supply chains, and the domestic economy, driven by construction and powered by flows of gravel, sand and government contracts. The latter supports the former: we can have an economy without TSMC, but we can’t have one without construction. The labor shortage has heavily impacted public construction in Taiwan. For example, the first phase of the MRT Wanda Line in Taipei, originally slated for next year, has been pushed back to 2027. The government

July 22 to July 28 The Love River’s (愛河) four-decade run as the host of Kaohsiung’s annual dragon boat races came to an abrupt end in 1971 — the once pristine waterway had become too polluted. The 1970 event was infamous for the putrid stench permeating the air, exacerbated by contestants splashing water and sludge onto the shore and even the onlookers. The relocation of the festivities officially marked the “death” of the river, whose condition had rapidly deteriorated during the previous decade. The myriad factories upstream were only partly to blame; as Kaohsiung’s population boomed in the 1960s, all household

Allegations of corruption against three heavyweight politicians from the three major parties are big in the news now. On Wednesday, prosecutors indicted Hsinchu County Commissioner Yang Wen-ke (楊文科) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), a judgment is expected this week in the case involving Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and former deputy premier and Taoyuan Mayor Cheng Wen-tsan (鄭文燦) of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is being held incommunicado in prison. Unlike the other two cases, Cheng’s case has generated considerable speculation, rumors, suspicions and conspiracy theories from both the pan-blue and pan-green camps.

Stepping inside Waley Art (水谷藝術) in Taipei’s historic Wanhua District (萬華區) one leaves the motorcycle growl and air-conditioner purr of the street and enters a very different sonic realm. Speakers hiss, machines whir and objects chime from all five floors of the shophouse-turned- contemporary art gallery (including the basement). “It’s a bit of a metaphor, the stacking of gallery floors is like the layering of sounds,” observes Australian conceptual artist Samuel Beilby, whose audio installation HZ & Machinic Paragenesis occupies the ground floor of the gallery space. He’s not wrong. Put ‘em in a Box (我們把它都裝在一個盒子裡), which runs until Aug. 18, invites