In the five-story building that houses Wang Film Production (

Wang Film is behind many major animation productions such as Mulan, The Lion King, Tarzan, Lilo & Stitch and The Little Mermaid. But as an OEM contractor to Disney, its name is not listed among the credits.

Wang Film, set up 22 years ago by James Wang (

Many employees of Wang Film see the company as the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp (TSMC) of the animation field. Like TSMC, Wang Film has been quietly earning foreign exchange for Taiwan over the last two decades -- but as yet, it doesn't have its own brand.

A senior animation artist surnamed Ho recalls:

"I remember back in the 1980s, the animators' union in the US had a dispute with their employers. The dispute became a stalemate and lasted a long time. It was at this time that US firms decided to shift production to Taiwan. At that time we had 800 animation artists, and we were all excited and exhausted. Every night we stayed up late working. Mr. Wang would order late-night snacks for everyone -- there was food for so many people it took a truck to deliver. It was an unforgettable time."

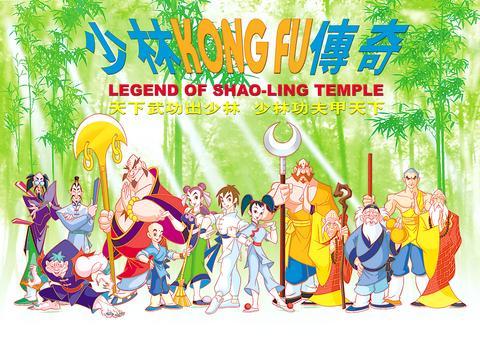

PHOTO COURTESY OF HONG YING UNIVERSE

It was a time when animation artists commanded high salaries, and, with all the overtime, they were able to take home NT$100,000 a month. These days, take-home pay is around NT$30,000 to NT$40,000 a month.

Although there is still plenty of work for Taiwan's animation artists, local firms working as an OEM manufacturer for the big US studios, see themselves as cut off from the big money.

To take the animation film The Lion King as an example, it is all too easy to see the unequal cut given to the manufacturer, as opposed to the copyright owner. The international box office for The Lion King was US$760 million, and the video revenue was US$780 million. Related merchandise rights were worth US$6 billion. In other words, The Lion King made Disney around US$7.5 billion, from which Wang Film, who did most of the production, was paid only US$67 million, just 0.9 percent of Disney's revenues from the film.

PHOTO COURTESY OF WANG FILM

Reflecting on this situation, James Wang said, "We've been carrying the sedan chair for others a long time now. It's time we set up our own brand." He said this during a meeting last year with premier Yu Shi-kun, who is behind an initiative to strengthen the animation industry in Taiwan.

Setting up their own brands has become a priority for many animation manufacturers in Taiwan. But this is not an easy task, for R&D is both capital and labor-intensive.

Hong Ying Universe (

Hsieh said the move to China was due to lower labor costs and the vast potential market.

"China's 380 million children have less money to spend on toys and entertainment than in many other parts of the world, but if this expenditure is brought up to the international average, US$34 a year, this would represent 30 percent of the world market," said Hsieh.

But can Taiwan take the lead in the China market? Both Wang and Hsieh agreed that there are problems. They pointed out that until the present time, Chinese cartoons have not produced a popular star like Donald Duck, Micky Mouse or Hello Kitty.

Hsieh of Hong Ying Universe sees the reason in the position that Taiwan still occupies in the production chain.

The production process of an animation film can be divided into pre-production, manufacturing and post-production. "What we've been doing is the middle part," she said. The characters have been designed, the shooting script has been written, and even the motion sequence has been roughly sketched out. "What we do is the composition, creating the backgrounds, making the animations [refining the motion] and articulating all these elements. Sometimes we do the rough cut. When all this is done, the product is sent back to the US for post-production, including dubbing, sound effects and visual effects.

"We are weakest in pre-production, designing characters and writing scripts for them," she said. This is a problem shared by Taiwan's conventional film industry. Wang Tung (

Within the animation industry, the problem is not confined to traditional animation -- painting on celluloid -- it also extends to computerized 3D animation.

Taiwan-based CG Computer Graphics (

It was not until last year that the company developed its own product with Master Q (

"For the character development and the script for the film, we need to rely on help from our partners in Japan and Europe," said Peggy Liou, marketing manager of CG.

So far, the biggest home-made animation project is Wang Film's Marco Polo, which is currently under development. The film is similar in scale to Disney's Mulan, with a budget estimated at US$40 million. "We will invest US$3 million purely in pre-production, developing the story and characters," said director Wang Tung. Although home grown, Wang Film plans to hire Tony Bancroft, director of Mulan and Toy Story 2 to direct the film.

Marco Polo, which takes place in China, is a clear attempt to cash in on the "Asian fever" of the last few years and it is hardly surprising that it has a very similar look to Mulan.

Still, local firms continue to seek a local style for future animations. Hong Ying Universe is currently involved on a project with the working title of The Legend of Panda (

Other projects include The Legend of Shaolin Temple, produced by Central Motion Picture Corp (CMPC) and manufactured by Hong Ying Universe, and The Monkey King (

Recently, the animation industry has also benefited from government support. Last year premier Yu Hsi-ku announced the expansion of subsidy and guidance programs for the digital content industry (ie software, animation and games industry), worth a total of NT$1.9 billion over the next six years.

As part of this move, the Industry Development Bureau of the Ministry of Economic Affairs (

"We appreciate the government's recognition of our efforts," said Wang Tung. "But we need more new talent. We need the kind of rapid policy-making and efficiency that has made Korea's software industry take off in the last three years," Wang said.

Facing strong competition from animation firms in the US and Japan, and the newly powerful Korea, Taiwan's animation firms recognize that they have a tough battle ahead.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global