"Welcome. Buy a jade bracelet. Jade dispels evil spirits," Mrs. Li cries from behind a mountain of shiny green, brown and white stones. "Or a ring, pendant, dragon, ancient cong, or statue of Buddha. Not expensive." At the next stall, her neighbor is selling stones carved into the shapes of mythological beasts and a variety of circular, square, and rhombic jades.

Camped out in the car park beneath the Chienkuo overpass like some high-class car boot sale, this is Taipei's Weekend Jade Market. Mobbed by local Taiwanese, it is becoming increasingly popular among bargain-hunting overseas visitors.

As well as jade and semiprecious rocks, the market also offers a wide range of articles connected with China's cultural heritage. These include bronze Bodhisattvas, embroidered clothing, carved walnuts, calligraphy executed on grains of rice, landscape paintings, turtle shells and teapots. In its few square meters, the Jade Market contains artifacts on a par with, or perhaps just copies of, items in Taiwan's best museums.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

Jade occupies a special place in Chinese people's affections that is sometimes difficult for Westerners to understand. Overseas visitors to the National Palace Museum are often as fascinated by the crowds bustling for a glimpse of the "jade cabbage" as by the vegetable itself.

"Jade occupies a special place in our hearts because it occupies a special place in Chinese history," explains Mr. Teng, who keeps a selective stall to the north end of the market. "The West never had a Jade Age; you went from flint axes of the Stone Age straight to the swords and ploughs of the Bronze Age. Your defining cultural moment is the Magna Carta, or the Industrial Revolution, or Windows 95."

"Not only did China have a distinctive Jade Age at the end of the Neolithic some three to six thousand years ago, but this was also the golden age of China's culture. During the ancient dynasties of the Hsia, Shang and Chou, Chinese invented writing and agriculture, we stopped being a bunch of hunting tribes and founded a nation; formulated the basic tenets of our religions and our civilization.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

"Because of its hardness, jade was used for tools such as knives, axes, hoes and chisels. Because of its luster, it was popular for pendants, hairpins and bracelets. From these important functions it came to symbolize wealth, nobility and power, and for communing with deities and ancestors."

"A thousand years later, it was to this pinnacle of civil and religious culture that Confucians and others looked back. Jades were thrown into rivers as a sacrifice to water gods and a jade cicada in the mouths of the dead symbolized resurrection. Because of its purity, jade embodied the Confucian virtue of a true gentleman.

"It has never lost its appeal. Now we are a democracy, everyone can afford a piece or two. Most Chinese will still tell you that a jade bracelet protects them from evil and, if the bracelet breaks, it is merely the breaking of your bad luck."

PHOTO: COURTESY OF NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM

Close examination of items on sale at the Jade Market supports Mr. Teng's view that many designs still conform to shapes dating back three of four thousand years, even if the workmanship may only date back three or four days. The six Authority Jades, symbolizing the various ranks of nobility, and six Worship Jades, used in sacrifices to heaven, earth and the four directions are still extremely popular.

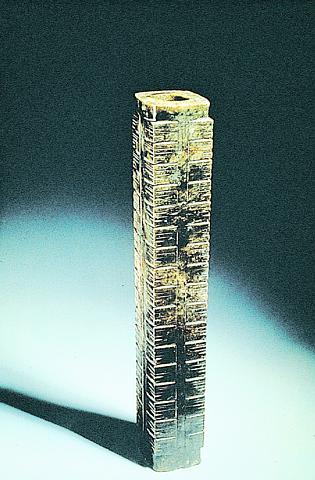

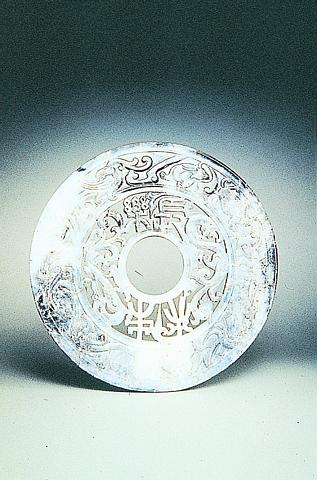

Most commonly seen are the bi, a round, flat disc with a circular hole in the center and the cong, an oblong tube of jade with a circular central cavity. These two represent circular heaven and square earth and, placed together on an altar, they acted as a conduit bringing spirits to earth and creating harmonious relations in society. Until recently cong were coveted as brush holders.

Gui are pointed tablets with a flat base which developed from end-bladed implements such as axes and spades. Different gui represented the insignia of various ranks of nobility who could participate in civil or sacred rites. Huang, semicircular jade ornaments worn as pendants, are often decorated with animals including dragons, birds, fish, and pig-dragons, many of which had totemic or religious significance. Zhang were used in ancient ceremonies and hu were held by officials during an audience with the monarch.

"Is it genuine?" is the most frequent question asked by Western visitors wishing to purchase a souvenir.

"Yes. And very ancient." is a frequent answer.

Bearing in mind that the Chinese word yu is used to refer to any beautiful stone not just to the nephrite and jadeite (silicates of calcium, magnesium, sodium or aluminum) encompassed by the English word "jade," they are not wrong -- all stone is ancient, even if unearthed and carved last week.

Perhaps Mrs Li's advice is best, "Just choose a piece you like. The only way to know if your jade is genuine or not, is to buy a cheap one. Then you may be sure it is not genuine."

For your information

The Weekend Jade Market is open beneath the Chienkuo S. Rd. overpass between Jenai and Chinan roads on Saturdays and Sundays.

The National Palace Museum at 221 Chihshan Rd. has a special

exhibition of Archaic Chinese Jades until April 10 in addition to its permanent exhibition of Chinese Jades.

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

It was just before 6am on a sunny November morning and I could hardly contain my excitement as I arrived at the wharf where I would catch the boat to one of Penghu’s most difficult-to-access islands, a trip that had been on my list for nearly a decade. Little did I know, my dream would soon be crushed. Unsure about which boat was heading to Huayu (花嶼), I found someone who appeared to be a local and asked if this was the right place to wait. “Oh, the boat to Huayu’s been canceled today,” she told me. I couldn’t believe my ears. Surely,

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she