In the town of Tungshih, the area in Taichung County hardest hit by the 921 earthquake, people camp out in parks as cranes reduce their homes to piles of rubble to be carted away by trucks. Some of them sit, almost comatose, quietly grieving lost relatives and ravaged lives. But ask them whether they plan to seek counseling and the answer is almost unanimous: "no."

"We don't plan to seek any help," says a young man surnamed Chan who is camped out with his parents, his wife and his children as they wait for the cranes to demolish their home. "My father and my kids went to a see a shoujing though."

Shoujing -- literally "receive shock" -- is a traditional Taoist method of dealing with the trauma of loss, and in Tungshih it is reaching far more people than modern psychiatry. Many rural Taiwanese traditionally trust only the time-honored methods of dealing with trauma and grieving associated with Buddhist and Taoist temples. Such traditional practices, and an unsophisticated view of modern psychological and psychiatric counseling, could make the psychological recovery even more difficult for the earthquake victims.

PHOTO: CHRIS TAYLOR, TAIPEI TIMES

According to Lu Chung-hsing, chief clinical psychologist at the Taipei Psychology Center, studies done in Kobe four years after the quake that hit there discovered high rates of personality and psychological disorders that resulted in similarly high patterns of divorce and sometimes suicide.

The problem facing Taiwan's psychological and psychiatric communities is how to intervene and nip as many of these problems in the bud as possible. It's a problem compounded by the fact that the earthquake struck in mostly rural Taiwan, where practices like shoujing take the place of modern counseling.

"Many people," says Lu, "think that seeking psychological help means they are crazy or out of their minds. Also they're reluctant to express their feelings in front of others or to show emotions such as crying. This prohibits them from seeking help."

PHOTO: CHRIS TAYLOR, TAIPEI TIMES

"If someone doesn't want to talk to a psychologist, that's fine," says Showline Chang, associate professor of psychology at Da-Yeh University, Taichung. "But we should still encourage people to seek professional help."

One man who is particularly sought after in the Tungshih area these days is Liu Hong-tu. An affable man in his late fifties with betel-stained teeth, a cell phone and a formidable Long Life cigarette habit, Liu seems an unlikely faith healer. But from his Tungshih home, which is called the Tiandao Yuan -- the Heavenly Way Court -- he has set out every morning and evening to give free treatments of shoujing to hundreds of traumatized Tungshih residents.

"Look!" he cries almost in glee over the grinding thump and crash of a crane that is demolishing two apartment blocks directly opposite his home. "Nearly every building in this street was destroyed. But my house and the houses on either side, are completely safe. We got green stickers. It was my powers that saved them."

His home is a small room cluttered with religious paraphenalia. Kuanyin -- the bodhisattva of compassion is pictured riding a dragon on the wall. At the back are two desks heaving with four ranks of gods. Back center is Kaitianzu -- the "ancestor who parted the earth and the heavens" (with an axe and a chisel) -- and the god who visited Liu at the age of 19 in a dream and blessed him with the powers he now uses to cure people of their pain.

What happened to the gods during the earthquake?

Liu smiles. "They all jumped down onto the front desk and huddled together. Not one of them fell off. Look. You can see. If they'd fallen onto the floor, they would have broken. But see. They're all intact."

For psychologist Lu Chung-hsing, one of the main tasks facing psychologists is helping people realize that the feelings of guilt many quake victims have of surviving when so many others died, and of having somehow not done enough to help, are normal feelings that can be talked through. Those who have lost loved ones, he points out, can be helped through a three-stage grieving process: first, acceptance of what has happened; second, integration, which involves a review of all their feelings about the person they have lost; and third, facing their new life without that person.

It's a process, he says, that can take one, two or maybe three years to complete, and it's a process that will be complicated by the fact that many of the people in central Taiwan facing such problems have to rebuild their material lives at the same time.

But for Liu Hong-tu the problem is far simpler. The entire project of modern psychology, with its century-old endeavor to map the human psyche, is a foreign land. For him, and for the many who seek his services, the problems engendered by a disaster like the 921 quake are spiritual.

"Fear has entered people's spirits," he says with a broad smile as he drags on a Long Life. "It can be driven away."

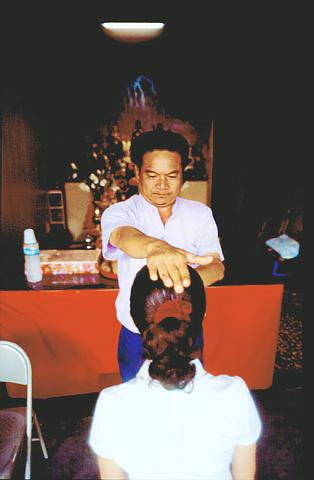

With this, he assumes a martial pose, knees bent, his left arm pointing towards the heavens, his right directed at the head of a young woman who is sitting with her back to him.

"The fear will end up in here," he says. And he picks up a small clay vial filled with raw rice. "When I start, the rice will be completely flat. But when I'm finished the surface will be uneven."

Sure enough, when he's done with his treatment, the formerly flat surface of the vial of rice on the desk before the arrayed gods is pitted and uneven.

At a riverside camp in Tungshih a crowd of people concur that shoujing can work wonders.

"My children were waking up all through the night crying after the quake," says a man surnamed Li. "But after taking them to a shoujing they've been fine."

Such attitudes are not a threat to most Taiwanese psychologists.

"Basically," says Showline Chang, "anything goes. It's whatever works. It's not our job to go out aggressively and grab people and say 'you need help.' But what will need to happen in the disaster zone over the coming months is individual and in depth counseling for those in need.'"

At the riverside relief camp in Tungshih, where an apartment block leans precariously nearby, and where a long line has formed outside McDonald's for a free evening meal, a lone woman sits slowly eating a hand-out bowl of rice and vegetables. She feels terrible, she says, like a beggar. And then tears start to well from the corners of her eyes as she recounts in a monotone how everyone in her family -- her husband, her children, her grandchildren -- were killed in the quake. No, she hasn't sought any help. Not even from the shoujing.

"I'm beyond help," she says.

People such as her, Chang believes, will have lost their basic trust in everything. In the ability of the land to stay still, even -- with their family gone -- in their own identity.

It will be people like this, beyond the help even of Taiwan's traditional soul doctors, that Taiwan's psychological community will need to bring all their modern training to bear in order to bring through the difficult task of rebuilding lives in devastated central Taiwan.

June 9 to June 15 A photo of two men riding trendy high-wheel Penny-Farthing bicycles past a Qing Dynasty gate aptly captures the essence of Taipei in 1897 — a newly colonized city on the cusp of great change. The Japanese began making significant modifications to the cityscape in 1899, tearing down Qing-era structures, widening boulevards and installing Western-style infrastructure and buildings. The photographer, Minosuke Imamura, only spent a year in Taiwan as a cartographer for the governor-general’s office, but he left behind a treasure trove of 130 images showing life at the onset of Japanese rule, spanning July 1897 to

In an interview posted online by United Daily News (UDN) on May 26, current Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) was asked about Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) replacing him as party chair. Though not yet officially running, by the customs of Taiwan politics, Lu has been signalling she is both running for party chair and to be the party’s 2028 presidential candidate. She told an international media outlet that she was considering a run. She also gave a speech in Keelung on national priorities and foreign affairs. For details, see the May 23 edition of this column,

At Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) urged the government to subsidize AI. “All schools in Taiwan must integrate AI into their curricula,” he declared. A few months earlier, he said, “If I were a student today, I’d immediately start using tools like ChatGPT, Gemini Pro and Grok to learn, write and accelerate my thinking.” Huang sees the AI-bullet train leaving the station. And as one of its drivers, he’s worried about youth not getting on board — bad for their careers, and bad for his workforce. As a semiconductor supply-chain powerhouse and AI hub wannabe, Taiwan is seeing

Jade Mountain (玉山) — Taiwan’s highest peak — is the ultimate goal for those attempting a through-hike of the Mountains to Sea National Greenway (山海圳國家綠道), and that’s precisely where we’re headed in this final installment of a quartet of articles covering the Greenway. Picking up the trail at the Tsou tribal villages of Dabang and Tefuye, it’s worth stocking up on provisions before setting off, since — aside from the scant offerings available on the mountain’s Dongpu Lodge (東埔山莊) and Paiyun Lodge’s (排雲山莊) meal service — there’s nowhere to get food from here on out. TEFUYE HISTORIC TRAIL The journey recommences with