It has long been obvious that something has gone askew with the UK’s ability to build. The planning paperwork for a modest-sized apartment block in London can run to more than 1,000 pages, whereas a few decades ago it might have been a handful. The documentation for the Lower Thames Crossing, a road and tunnel project under consideration since the early 2000s, exceeds 350,000 pages. The planned HS2 high-speed railway has become smaller and smaller, yet its cost continues to spiral to multiples of the original price tag. And so on.

The reality struck home for me when I walked around the vast and moribund HS2 terminus site at Euston in London a couple of years ago. It was remarkable — and dispiriting — that we would rip up such a large tract of central London, disrupting businesses and condemning residents to live beside an eyesore, only to leave it lying fallow into the indefinite future (some skeptics doubt the line would ever reach Euston).

The UK just cannot seem to break out of its rut of subpar economic growth and address challenges such as inadequate housing and energy supply, without overcoming this syndrome of bureaucracy and inertia. What to do?

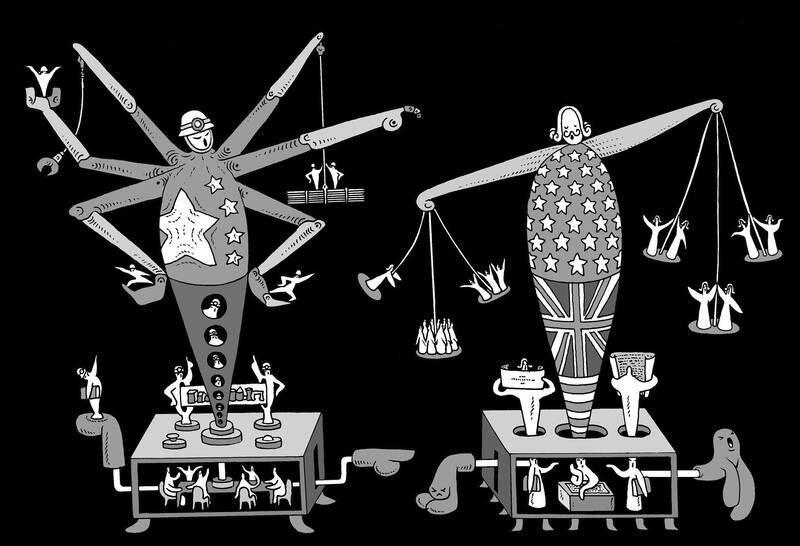

Illustration: Mountain People

Things were very different in China. I first visited Shanghai in 1993, when cars moved at a snail’s pace through narrow streets that were clogged from curb to curb with bicycles. Returning a decade later, the city was barely recognizable. I took a taxi from Hongqiao Airport along an elevated highway that cut a swathe through the center of the city to the Huangpu River, where on the eastern bank a cluster of modern skyscrapers had materialized that resembled the Manhattan skyline. The pace of development was hard to take in. During the five years I lived in Shanghai, it did not slow down. This was only a sliver of what was being replicated throughout the country.

China was playing catch-up in those days, but we are now far beyond that point. The knowledge and expertise accumulated from the largest building boom in history has driven the nation to engineering feats unsurpassed elsewhere. Social media abounds with effusive accounts of China’s infrastructure achievements.

Take the Huajiang Canyon Bridge in Guizhou, a mountainous province that is one of the country’s poorest. The suspension bridge scheduled to open next month spans a chasm and would be the world’s highest, measuring 625m from the deck to the gorge below. China’s high-speed rail network, developed since 2008, is bigger than the rest of the world’s combined. The country has constructed power plants equivalent to the UK’s total supply every year for the past quarter-century. Its expressway network, built in the past 30 years, is twice the length of the US interstate system.

A similar evolution has unfolded in manufacturing and technology. Western economies originally began outsourcing production to China for its cheap labor (as well as a huge domestic market). However, the country did not remain a low-cost assembler. Manufacturing at scale year after year in highly competitive conditions builds practical know-how and seeds the capacity for innovation. China is now out-competing and out-innovating Western carmakers in electric vehicles, barely two decades after its companies were putting together models for these foreign rivals and had few designs of their own. The country has established a similarly dominant position in renewable energy infrastructure.

How to reckon with the rise of China might be the issue of the age for all democratic countries; the world’s future would turn, in large part, on its evolving strategic competition with the US. The UK would not merit much more than a footnote in that larger drama, even if it was once the world’s greatest industrial innovator and leading power, but it shares some of the pathologies that threaten the US’ ability to sustain its global economic and geopolitical supremacy — above all, a system that has elevated rules and processes over outcomes, as Dan Wang, a research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover History Lab, argues in Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future.

In Wang’s view, the defining distinction between the two superpowers is that China is run by engineers, while the US is run by lawyers — and each could benefit from becoming a bit more like the other. If that is a valid take on the US, it is just as true of the UK. Five of the past 10 US presidents attended law school while only two — Herbert Hoover and Jimmy Carter — worked as engineers, according to the book. An engineer has never been prime minister of the UK. Former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher came closest, having worked as a research chemist before entering politics. She was also a barrister, like a preponderance of British leaders stretching back two centuries (including the incumbent, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer).

The parallels do not end there. The book contrasts the success of China’s high-speed rail network with attempts to build a link from San Francisco to Los Angeles. California’s project is a mirror image of HS2: delayed, truncated, massively over budget. As in the UK, the consequences of a process-obsessed culture can be seen in inadequate housing, missing mass transit systems and dilapidated infrastructure. Engineers are problem-solvers who get things done; lawyers are better at blocking things (often for good reason, but still). This appears to be a peculiarly anglophone problem. Bureaucracy has eroded the can-do spirit that made the US and the UK, in different periods, construction pioneers.

Wang, who was born in Toronto to Chinese parents and worked as a technology analyst in Beijing and Shanghai, is not the first to point out that China’s government includes a lot of engineers or that the US is a litigious place. However, his framing serves a useful purpose, illuminating a pivotal difference. Many recoil instinctively at the suggestion that liberal democracies should copy China — because the flip side of its undeniable physical achievements is a Communist Party system that restricts and disregards individual rights and freedoms to a degree that few in the West would find acceptable. Is there a way to take lessons from what works well in China without importing the less palatable aspects of its model?

Breakneck can be seen as an attempt to thread this needle. It is no panegyric, with chapters on the brutalities of the one-child policy and the shock of the zero-COVID-19 lockdown in Shanghai, which disabused residents of China’s richest and most cosmopolitan city of any illusion that they were above the remorseless collective logic of the state machine. The engineering state moves fast and breaks things — and people. Point it in the right direction, and you might get spectacular results. Pick the wrong objective, and you get disaster and atrocities.

The great and enduring advantage of the democratic system is its open-endedness and ability to adapt. We are again at an inflection point that demands a change of direction. China, for all its economic challenges and difficulties, is not standing still. Failure to heed the warning signs might mean the US and its allies ceding the technological race and global influence. Will we rise to the challenge?

Matthew Brooker is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business and infrastructure. Formerly, he was an editor for Bloomberg News and the South China Morning Post. This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Many foreigners, particularly Germans, are struck by the efficiency of Taiwan’s administration in routine matters. Driver’s licenses, household registrations and similar procedures are handled swiftly, often decided on the spot, and occasionally even accompanied by preferential treatment. However, this efficiency does not extend to all areas of government. Any foreigner with long-term residency in Taiwan — just like any Taiwanese — would have encountered the opposite: agencies, most notably the police, refusing to accept complaints and sending applicants away at the counter without consideration. This kind of behavior, although less common in other agencies, still occurs far too often. Two cases

In a summer of intense political maneuvering, Taiwanese, whose democratic vibrancy is a constant rebuke to Beijing’s authoritarianism, delivered a powerful verdict not on China, but on their own political leaders. Two high-profile recall campaigns, driven by the ruling party against its opposition, collapsed in failure. It was a clear signal that after months of bitter confrontation, the Taiwanese public is demanding a shift from perpetual campaign mode to the hard work of governing. For Washington and other world capitals, this is more than a distant political drama. The stability of Taiwan is vital, as it serves as a key player

Yesterday’s recall and referendum votes garnered mixed results for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). All seven of the KMT lawmakers up for a recall survived the vote, and by a convincing margin of, on average, 35 percent agreeing versus 65 percent disagreeing. However, the referendum sponsored by the KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on restarting the operation of the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant in Pingtung County failed. Despite three times more “yes” votes than “no,” voter turnout fell short of the threshold. The nation needs energy stability, especially with the complex international security situation and significant challenges regarding

Most countries are commemorating the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II with condemnations of militarism and imperialism, and commemoration of the global catastrophe wrought by the war. On the other hand, China is to hold a military parade. According to China’s state-run Xinhua news agency, Beijing is conducting the military parade in Tiananmen Square on Sept. 3 to “mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II and the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.” However, during World War II, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had not yet been established. It