The world economy remains beset by challenges, from tight monetary, financial and fiscal conditions to the effects of the war in Ukraine. These headwinds are impeding global growth — which is expected to slow to 3 percent this year, compared to 3.5 percent in 2022 — damaging lives and livelihoods, with poverty and food insecurity on the rise, particularly in developing countries. In addressing the complex and overlapping challenges the world faces, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is a region with much to offer.

For starters, LAC countries can help create a more resilient global food market. As early as 2017, the World Economic Forum facilitated a joint ministerial declaration calling for the region to become the “breadbasket of the world.” At last year’s Summit of the Americas, hosted by the US, participants released an Agriculture Producers Declaration underscoring the important role of major LAC exporters in strengthening global food security.

The reason is obvious. With one-quarter of the world’s arable land and one-third of its freshwater resources, the LAC already comprises the largest net food exporter among world regions. What is needed now is new investment, especially in physical and digital infrastructure and in climate-resilient agriculture, continued technological and competitiveness improvements and better integration into regional and global value chains.

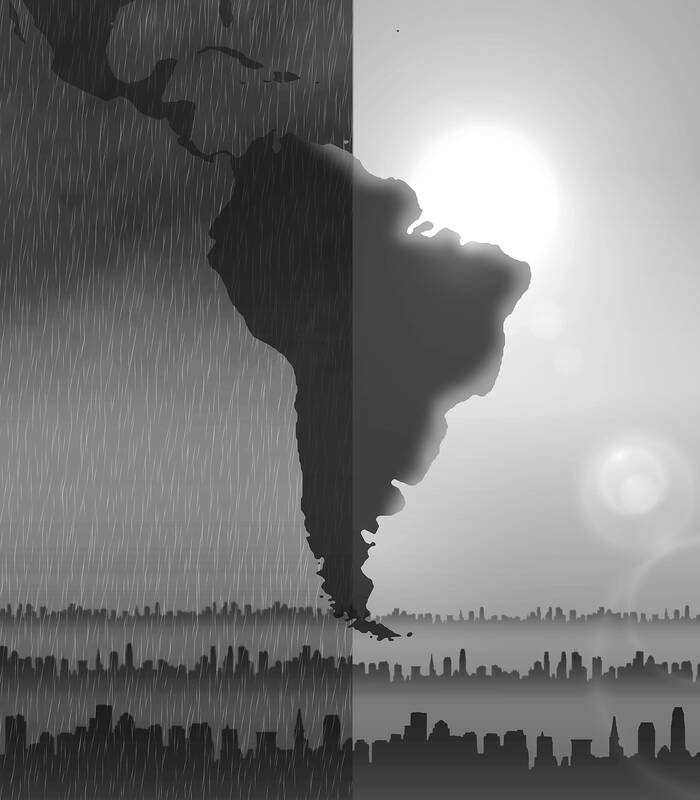

Illustration: Yusha

Beyond food, the region is well-positioned to become a global climate leader. LAC countries account for less than 10 percent of global greenhouse-gas emissions, and are home to trailblazers in the quest for a green and just transition. For example, Costa Rica and Uruguay were among the first countries in the world to start generating nearly all domestic electricity from renewable sources. Even carbon-intensive economies, such as Colombia, are now undertaking ambitious reforms to mitigate climate change.

More important, with two-thirds of the world’s lithium reserves and 40 percent of its copper reserves — both essential to climate-friendly technologies — the region holds the key to curbing emissions everywhere and will play a major role in ensuring that these critical minerals are sourced and processed in environmentally and socially sustainable ways. This explains why these resources featured prominently in the recently announced 45 billion euro (US$49 billion) EU-LAC Global Gateway Investment Agenda.

LAC countries also have an important role to play when it comes to climate adaptation. With climate change already affecting vulnerable communities in the region, these countries are offering valuable insights into the dangers that lie ahead and into the virtues and limits of current adaptation strategies — and becoming increasingly influential in global discussions. Already, Barbados played a prominent role in the Paris Summit for a New Global Financing Pact in June this year. Brazil is to assume the G20 presidency at the end of this year and host the UN climate summit (COP30) in 2025.

More broadly, LAC countries are experimenting with, and mainstreaming, innovative instruments that link policy, climate, nature and finance. The Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility provides a financial buffer against increasingly frequent extreme weather.

Furthermore, in May, Ecuador completed the world’s largest-ever debt-for-nature swap, generating US$323 million in savings to finance conservation projects. This followed Belize’s landmark 2021 debt-for-nature swap, widely hailed as a successful model for subsequent conversions.

Last year, Chile and Uruguay issued the world’s sovereign sustainability-linked bonds. Moreover, Colombia became the first country in the western hemisphere to adopt a national green taxonomy, a classification tool that enables lenders and borrowers to identify economic activities that contribute to environmental goals. This year, Mexico unveiled its own sustainable taxonomy, covering both environmental and social objectives.

LAC countries are also bringing their experience to bear on other vital global policy discussions. Consider inflation, a frequent challenge in the region. Over the past two years, many LAC central banks hiked interest rates more quickly and aggressively than their advanced-economy counterparts. The policy appears to have paid off: The region, excluding Venezuela and Argentina, kept inflation below the OECD average last year (though complacency must be avoided).

At the same time, the region is devising potentially transferable approaches to international migration and displacement, which remain high worldwide as a result of humanitarian, economic, climate or other factors. For example, the socioeconomic integration of Venezuelan migrants in host communities in Colombia and elsewhere makes for a useful case study.

There is no shortage of areas where LAC countries can leverage their strengths to assert global leadership. Yet if the region is to seize the opportunities ahead, it must prepare itself better by accelerating development progress at home.

Many LAC countries need to do more to advance and balance their growth, fiscal and equity goals. Rigorous policymaking is urgently needed amid continued inflationary pressures and risk-off sentiment. On the micro front, productivity and labor-market improvements are essential to repair the damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and make the most of the region’s most valuable asset: human capital.

Sound public policy, strong institutional capacity and more effective and efficient government programs will be vital to address these macro and micro challenges and ensure socioeconomic progress. Greater regional integration would also help by supporting the protection and development of regional and global public goods. Collaboration with the private sector, civil society, multilateral organizations and the international community would also be indispensable.

Can the region meet its potential for global leadership? We certainly hope so. A more resilient, sustainable and inclusive LAC can help build a world that is greener, more energy-secure and better fed, while contributing solutions to the most pressing global policy and governance challenges. At this critical moment, what is good for Latin America and the Caribbean is good for the world.

Pepe Zhang is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. Otaviano Canuto is a former vice president and executive director of the World Bank, executive director of the IMF, vice president of the Inter-American Development Bank and vice minister of finance of Brazil. He is a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Many foreigners, particularly Germans, are struck by the efficiency of Taiwan’s administration in routine matters. Driver’s licenses, household registrations and similar procedures are handled swiftly, often decided on the spot, and occasionally even accompanied by preferential treatment. However, this efficiency does not extend to all areas of government. Any foreigner with long-term residency in Taiwan — just like any Taiwanese — would have encountered the opposite: agencies, most notably the police, refusing to accept complaints and sending applicants away at the counter without consideration. This kind of behavior, although less common in other agencies, still occurs far too often. Two cases

In a summer of intense political maneuvering, Taiwanese, whose democratic vibrancy is a constant rebuke to Beijing’s authoritarianism, delivered a powerful verdict not on China, but on their own political leaders. Two high-profile recall campaigns, driven by the ruling party against its opposition, collapsed in failure. It was a clear signal that after months of bitter confrontation, the Taiwanese public is demanding a shift from perpetual campaign mode to the hard work of governing. For Washington and other world capitals, this is more than a distant political drama. The stability of Taiwan is vital, as it serves as a key player

Yesterday’s recall and referendum votes garnered mixed results for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). All seven of the KMT lawmakers up for a recall survived the vote, and by a convincing margin of, on average, 35 percent agreeing versus 65 percent disagreeing. However, the referendum sponsored by the KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on restarting the operation of the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant in Pingtung County failed. Despite three times more “yes” votes than “no,” voter turnout fell short of the threshold. The nation needs energy stability, especially with the complex international security situation and significant challenges regarding

Most countries are commemorating the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II with condemnations of militarism and imperialism, and commemoration of the global catastrophe wrought by the war. On the other hand, China is to hold a military parade. According to China’s state-run Xinhua news agency, Beijing is conducting the military parade in Tiananmen Square on Sept. 3 to “mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II and the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.” However, during World War II, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had not yet been established. It