COVID-19 is a human disaster, but for one group of animals, there might be a silver lining.

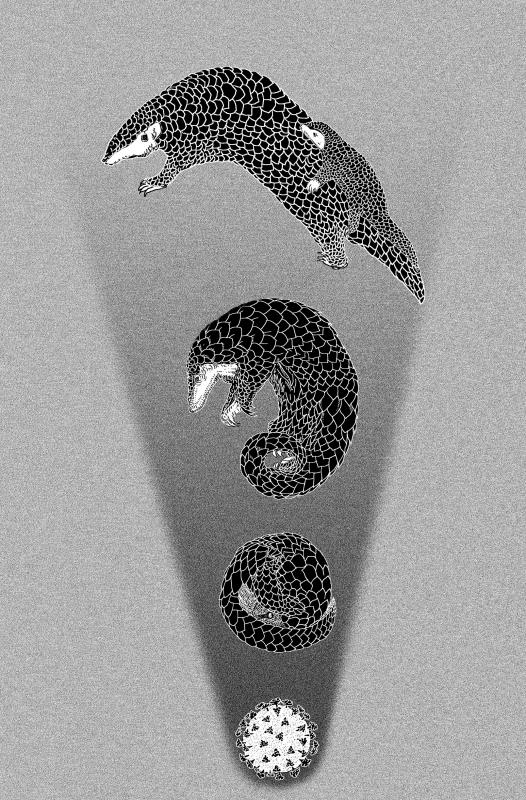

Pangolins are one of the most heavily trafficked animals in the world, and as a result they are endangered, but in the past few weeks they have been linked to the initial COVID-19 outbreak in China.

The evidence is inconclusive, but it has already prompted the Chinese government to take action. If more actions against the wildlife trade follow, the incident could prove to be a turning point for pangolin conservation.

Illustration: Mountain People

A key question is where COVID-19 came from. Many animals carry coronaviruses and are potential sources of infection. That is important to know, if only because it should help prevent future outbreaks.

Several ideas have been proposed, but arguably the most dramatic is that pangolins were the source.

Pangolins look like scaly anteaters. Uniquely among mammals, their bodies are covered in hard protective scales made of keratin: the same material as human nails.

They feed on insects such as ants and termites, and are often nocturnal and shy.

While they look like anteaters, they are not closely related to them, and their closest living relatives are actually carnivorans: the group that includes wolves and cats.

There are eight species of pangolin. Four live in Africa and four in Asia. All are at risk of extinction, International Union for Conservation of Nature data shows.

Two of the African species are considered vulnerable and two are endangered. Of the Asian species, one is endangered while the other three are critically endangered.

Pangolins are illegally hunted and traded for two main reasons: First, their meat is considered a delicacy in several Southeast Asian countries, especially China and Vietnam.

Second, their scales are used in Chinese traditional medicine.

As a result, they are the world’s most trafficked mammals.

The idea that pangolins are the source of COVID-19 emerged at a Feb. 7 news conference given by the South China Agricultural University in Guangzhou, China. Two scientists there, Yongyi Shen (沈永義) and Lihua Xiao (肖立華), were said to have compared coronaviruses from pangolins and from humans infected in the outbreak.

The viruses’ genetic sequences were said to be 99 percent similar. One coauthor, Wu Chen (陳武) of Guangzhou Zoo, had previously helped show that Sunda pangolins carry coronaviruses.

However, the results had not been published at that stage, so other scientists could not examine them in detail. Meanwhile, there were many other possibilities.

The virus could have come from an animal and seafood market in Wuhan, where many species were held. Animals in such markets are often kept in closely packed, unsanitary conditions, with many people nearby: a perfect opportunity for a virus to jump species.

Many pointed the finger at bats: The virus is genetically similar to those in bats, and it would not be the first time a disease passed from bats to humans. There was also a study linking the virus to one found in snakes, but this is now considered unlikely.

Then there was a twist in the story. On Feb. 20, the researchers posted a preliminary version of the study on the preprint site bioRxiv. The conclusions were radically different to what was described at the news conference.

Although the pangolin virus was “genetically related” to the one infecting humans, it was “unlikely to be directly linked to the outbreak because of the substantial sequence differences.”

The 99 percent similarity was only in one region of the genome. Across the entire genome, the similarity was only 90.3 percent.

There had been an “embarrassing miscommunication between the bioinformatics group and the lab group of the study.”

When contacted by the Observer, Xiao declined to comment.

However, the Chinese government was already lurching into action. On Feb. 24, China announced an immediate ban on trading and eating many wild animals, including pangolins. Officials began shutting down wild animal markets across the country.

This was the latest in a series of steps that ought to reduce the pangolin trade. In 2016, the international trade in pangolins was entirely banned by the 183 nations that signed up to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species.

All eight pangolin species were placed in Appendix I of the Convention, giving them the strictest protection currently possible.

However, so far this does not seem to have resulted in a drop in the number of pangolins traded, says Xu Ling (徐玲), China director at wildlife trade monitoring group TRAFFIC in Cambridge, England. The trade continues, but the nature of the shipments has changed.

“Before 2016, we could find frozen pangolin bodies, the meat smuggled in from other parts of Southeast Asia to China,” Ling said.

Nowadays, most shipments are purely pangolin scales. Often they come from Africa, after being illicitly shipped out via Nigeria.

More recently, in August last year, China’s state insurance providers announced that they would stop covering medicines made from pangolin scales. The move took effect in January.

Against this background, it is unclear what impact China’s new ban on eating wild meat will have on pangolins.

“Even without this ban, pangolin meat consumption was forbidden in China,” Ling said, as pangolins had protected status.

This was reflected in the shift to importing scales. These are only legal if they come from certified sources, but, as so often happens, the traders find ways around that.

In the longer term, the loss of insurance funding might undercut the scale market.

Meanwhile, the idea that pangolins played a role in the emergence of COVID-19 has not gone away.

On March 17, a team led by Kristian Andersen at Scripps Research in La Jolla, California, published a detailed analysis of the virus’ possible origin in Nature Medicine.

They said that the ultimate source is likely to be bats, just as it was for the two other coronavirus outbreaks of recent years: SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS).

Bats are a known reservoir of coronaviruses. Furthermore, intermediate horseshoe bats are known to carry a virus called RaTG13, whose genome is 96 percent identical to that of SARS-CoV-2.

“It’s pretty clear the bat serves as the reservoir for this,” Andersen said.

The question is how the virus traveled from bats to humans.

“We are entertaining two different scenarios,” Andersen said.

The key question is how the virus acquired certain sequences of its genome, which allow it to bind strongly to human cells and thus infect them. The bat virus does not have these sequences.

One possibility is that the bat virus made the jump to humans several months before the outbreak was detected.

These early viruses would not have been especially infectious or dangerous, but they could have mutated and evolved to acquire the key genetic sequences that made them infectious.

The alternative possibility is that there was an intermediate host.

“That’s where the pangolins come in,” Andersen said.

While the pangolin virus as a whole is less similar to SARS-CoV-2 than the bat virus, the pangolin virus genome does have the crucial binding sequences.

This is what Shen, Xiao and their colleagues found — and it has now been supported by a further study from another Chinese group.

Furthermore, a study published on March 26 in Nature discovered viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2 in pangolins that had been smuggled into China. These viruses had binding sequences similar to those in the human viruses.

“Where it’s really important is where they’re identical,” Andersen said. “While the bat virus overall is more similar, in the regions where it really matters it’s actually quite different.”

This suggests that the bat and pangolin viruses met, perhaps in the same host, and exchanged genes. Some of the bat viruses ended up with the key binding sequences from the pangolin viruses, enabling them to infect humans and unleash a pandemic.

“Recombination is frequent in these types of viruses,” Andersen said. “It’s speculative, but it’s highly likely that that’s how we ended up with this new virus.”

A similar story played out before the SARS outbreak of 2002 to 2004. The original source of the virus was wild bats, and in 2017 researchers managed to identify a cave in China where the bats carry viruses that are virtually identical to SARS.

However, the virus was probably passed to humans by civets, which are cat-like animals, leading to China imposing a temporary ban on selling civets.

The more recent MERS outbreak probably moved from bats to humans through camels.

Andersen said that it is not yet certain which scenario is correct. Even if there was an intermediate host, it might not have been pangolins.

“We cannot conclude if pangolins are indeed [the] intermediate species,” said Arinjay Banerjee, a virologist at McMaster University in Canada.

The question of whether pangolins contributed to the COVID-19 outbreak would not be settled any time soon.

“It’s probably going to be a long, drawn-out question,” Andersen said.

Resolving the origin of SARS took years.

However, it might be crucial to ending the pangolin trade, because doing so requires two things. The first is strict enforcement of the rules, which China seems to want to do — it was stepping up enforcement even before the outbreak.

The second is for people to stop buying pangolin products. If there is no demand, the illegal trade would become unprofitable, and suppliers would abandon it.

“Just the fact there’s been all this publicity about the potential link to pangolins will probably lead to plummeting demand for them,” said TRAFFIC global communications coordinator Richard Thomas.

There is evidence that he is right. Yuhan Li of the University of Oxford said that Chinese conservation organizations have been circulating a questionnaire on social media to see how people’s attitudes have shifted.

More than 100,000 people have responded, and more than 90 percent said that they would support a total ban on the trade in wild animals, no matter what the intended purpose.

It is unclear if people would stick to this once the COVID-19 crisis has passed, but Ling is planning a campaign to strengthen opposition.

The realization that wildlife markets allow diseases to spread to people might spur action.

When China announced the ban, the WWF called it “a timely, necessary and critical step” — not just for safeguarding the wild animals, but for human health.

“This public health crisis must serve as a wake-up call to end the unsustainable use of endangered animals and their parts, whether as exotic pets, for food consumption or for their perceived medicinal value,” it said.

In the best-case scenario, it would not just be pangolins that benefit. Reducing the demand for illegally traded wildlife would help many species — and protect people from future pandemics into the bargain.

The government and local industries breathed a sigh of relief after Shin Kong Life Insurance Co last week said it would relinquish surface rights for two plots in Taipei’s Beitou District (北投) to Nvidia Corp. The US chip-design giant’s plan to expand its local presence will be crucial for Taiwan to safeguard its core role in the global artificial intelligence (AI) ecosystem and to advance the nation’s AI development. The land in dispute is owned by the Taipei City Government, which in 2021 sold the rights to develop and use the two plots of land, codenamed T17 and T18, to the

Taiwan’s first case of African swine fever (ASF) was confirmed on Tuesday evening at a hog farm in Taichung’s Wuci District (梧棲), trigging nationwide emergency measures and stripping Taiwan of its status as the only Asian country free of classical swine fever, ASF and foot-and-mouth disease, a certification it received on May 29. The government on Wednesday set up a Central Emergency Operations Center in Taichung and instituted an immediate five-day ban on transporting and slaughtering hogs, and on feeding pigs kitchen waste. The ban was later extended to 15 days, to account for the incubation period of the virus

The ceasefire in the Middle East is a rare cause for celebration in that war-torn region. Hamas has released all of the living hostages it captured on Oct. 7, 2023, regular combat operations have ceased, and Israel has drawn closer to its Arab neighbors. Israel, with crucial support from the United States, has achieved all of this despite concerted efforts from the forces of darkness to prevent it. Hamas, of course, is a longtime client of Iran, which in turn is a client of China. Two years ago, when Hamas invaded Israel — killing 1,200, kidnapping 251, and brutalizing countless others

Art and cultural events are key for a city’s cultivation of soft power and international image, and how politicians engage with them often defines their success. Representative to Austria Liu Suan-yung’s (劉玄詠) conducting performance and Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen’s (盧秀燕) show of drumming and the Tainan Jazz Festival demonstrate different outcomes when politics meet culture. While a thoughtful and professional engagement can heighten an event’s status and cultural value, indulging in political theater runs the risk of undermining trust and its reception. During a National Day reception celebration in Austria on Oct. 8, Liu, who was formerly director of the