When Paris’s Notre-Dame Cathedral caught fire on April 15, it was only a matter of minutes before conspiracy theories were swirling across social media.

Some were from far-right accounts and outlets desperate to blame the blaze on some kind of Islamist attack. As the inferno was broadcast worldwide, Web sites such as US-based Infowars pushed out reams of unverified and often false information, speculation and rhetoric.

“The West has fallen,” right-wing documentary filmmaker Mike Cernovich tweeted.

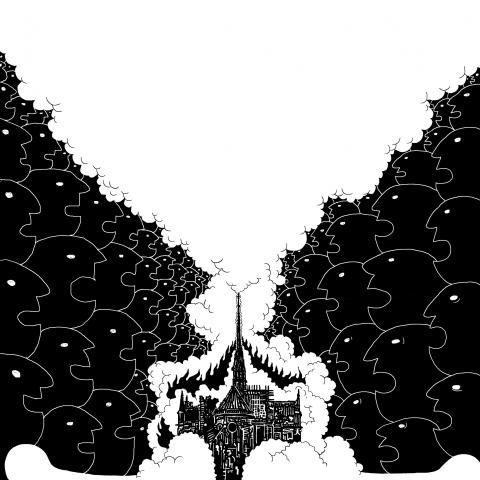

Illustration: Mountain People

According to the EU’s specialist disinformation monitoring unit, these messages were then further picked up, amplified and spread by a host of Russian-linked accounts, platforms and automated trolls.

They added new, often deeply implausible theories. As well as blaming Islamists, some suggested France’s yellow vest protesters might be responsible. Others suggested unlikely Ukrainian links to the fire, while one — completely without evidence — speculated that the pope himself would call for a mosque to be built on the medieval cathedral’s ruins.

The latter claim came from the Web site of the Kremlin-supporting Tsargrad TV — which pushes a relentlessly nationalist pro-Russian Orthodox Church line highly supportive of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Its sheer implausibility points to a growing trend in the growing ideological battles on social media and the Internet in which the truth can appear increasingly irrelevant.

How to handle this — and whether, when, how and if to exploit it — is a growing challenge for almost every country.

In the aftermath of last weekend’s Easter bombings that killed more than 250, Sri Lanka imposed an outright — if not always effective — block on multiple social media, including Facebook, WhatsApp and Snapchat.

That followed widespread condemnation of social media after the New Zealand mosque shooting the previous month, when unedited footage streamed by the gunman was widely distributed.

How effective such restrictions are remains in question. They might be counterproductive, simply adding to the air of crisis. In Sri Lanka, many users were able to find ways around the block, not least to reassure friends and family they were safe. By activating a function whereby users could mark themselves unharmed after attacks and disasters, the tech firm might have contributed to the ban’s failure, whether willingly or not.

Such draconian action can also simply reinforce the narrative that a government has something to hide — particularly in Sri Lanka’s case, where warnings of an imminent attack from other intelligence services might have been ignored.

What does appear clear is that the Internet and social media have become something of a cesspool for hatred and conspiracy, and that powerful forces wish to use that to their advantage. What is equally clear is that those who wish to stop them have yet to find a strategy that truly works.

Getting moderators to review and remove potentially harmful content has been the preferred route of many platforms, but it is often a losing battle, people involved in the process have said.

Newspaper comment sections can remain full of racist, misogynist and similar comments, as can Facebook, despite hiring an army of often poorly paid contractors to remove material that it claims breaches its ever-evolving terms of use.

Those who have done the job describe it as an unending nightmare of pornography, violence – including beheadings, child abuse and more — along with sexist, racist and brutally misogynist rants. Contractors are timed to make fast decisions and report horrific mental health issues in consequence. Without them, even more of that material would doubtless reach a wider audience — but even stopping that would only tackle the tip of the iceberg.

These problems are not new. Sectarian, racist and divisive language and rumor have long been a potent tool for populists, xenophobes and anyone else seeking to foster division, fear and distrust to entrench their own control. In many locations — for example, the Indian subcontinent — things used to be much worse.

In 1983, a much smaller attack by Tamil Tiger rebels on government troops triggered massive ethnic riots against Tamils in the capital, killing hundreds and jump-starting a quarter-century-long war.

India’s Sikhs suffered similar attacks the next year following the assassination of then-Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Much worse communal violence was orchestrated during India’s 1947 partition by radio, leaflet and rumor, long before the advent of the Internet.

The effect of social media can be rapid — but it can also be slower and even more insidious. In private Facebook and WhatsApp groups, truth often does not matter, and conversations and memes can swiftly prove self-reinforcing.

In Western politics, that increasingly includes Islamaphobia, anti-Semitism or both, often couched as part of a wider backlash against liberal multicultural elites and norms.

This is a world created by modern technology and political frustration, particularly among the perceived “losers” of globalization, but it is a situation that some actors in particular — Russia, the far right and Islamist groups such as the Islamic State — have learned to exploit.

A study this year by the NATO Strategic Indications Centre of Excellence found that a majority of the accounts on Russian social media site VK that were trolling against Western military activity in Eastern Europe were automated and robotic.

Such tools are increasingly for sale. A separate report by the same center identified an increasingly lucrative black market in often illegal social media manipulation software, data and other products, allowing users to buy “likes,” comments, ads and fake personas.

Many are easy to spot — but improved artificial intelligence and machine learning might soon make that more difficult.

Perhaps the best pointer on how to tackle this comes from the Christchurch mosque massacre in New Zealand. While still criticizing social media, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Arden spent most of her time on more practical solutions — introducing gun control and pushing forward a more inclusive vision of the country that blunted the attacker’s message.

Whether that will be enough is another question. If the West ever genuinely falls, it is as likely to do so through social media-fueled bigotry, division and deceit as any physical attack.

Peter Apps is a columnist who writes on international affairs, globalization and conflict, and is the founder and executive director of the Project for Study of the 21st Century think tank. The opinions expressed here are those of the author.

The gutting of Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) by US President Donald Trump’s administration poses a serious threat to the global voice of freedom, particularly for those living under authoritarian regimes such as China. The US — hailed as the model of liberal democracy — has the moral responsibility to uphold the values it champions. In undermining these institutions, the US risks diminishing its “soft power,” a pivotal pillar of its global influence. VOA Tibetan and RFA Tibetan played an enormous role in promoting the strong image of the US in and outside Tibet. On VOA Tibetan,

Former minister of culture Lung Ying-tai (龍應台) has long wielded influence through the power of words. Her articles once served as a moral compass for a society in transition. However, as her April 1 guest article in the New York Times, “The Clock Is Ticking for Taiwan,” makes all too clear, even celebrated prose can mislead when romanticism clouds political judgement. Lung crafts a narrative that is less an analysis of Taiwan’s geopolitical reality than an exercise in wistful nostalgia. As political scientists and international relations academics, we believe it is crucial to correct the misconceptions embedded in her article,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,

US President Trump weighed into the state of America’s semiconductor manufacturing when he declared, “They [Taiwan] stole it from us. They took it from us, and I don’t blame them. I give them credit.” At a prior White House event President Trump hosted TSMC chairman C.C. Wei (魏哲家), head of the world’s largest and most advanced chip manufacturer, to announce a commitment to invest US$100 billion in America. The president then shifted his previously critical rhetoric on Taiwan and put off tariffs on its chips. Now we learn that the Trump Administration is conducting a “trade investigation” on semiconductors which