China has invested billions of dollars to increase its soft power, but it has recently suffered a backlash in democratic countries. A new report by the National Endowment for Democracy argues that we need to rethink soft power, because “the conceptual vocabulary that has been used since the Cold War’s end no longer seems adequate to the contemporary situation.”

The report describes the new authoritarian influences being felt around the world as “sharp power.” A recent cover article in The Economist defines “sharp power” by its reliance on “subversion, bullying and pressure, which combine to promote self-censorship.”

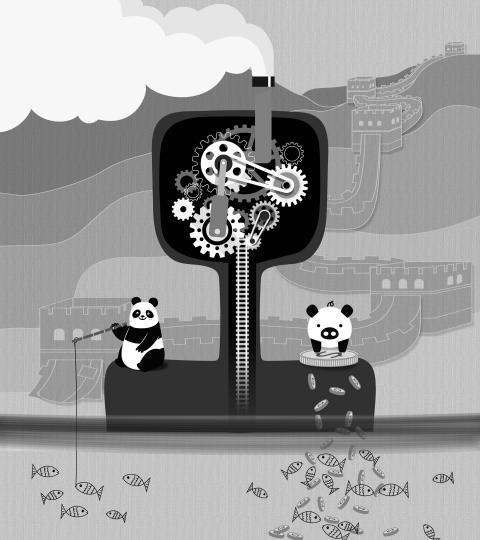

Whereas soft power harnesses the allure of culture and values to augment a country’s strength, sharp power helps authoritarian regimes compel behavior at home and manipulate opinion abroad.

Illustration: June Hsu

The term “soft power” — the ability to affect others by attraction and persuasion rather than the hard power of coercion and payment — is sometimes used to describe any exercise of power that does not involve the use of force. However, that is a mistake. Power sometimes depends on whose army or economy wins, but it can also depend on whose story wins.

A strong narrative is a source of power. China’s economic success has generated both hard and soft power, but within limits. A Chinese economic aid package under the Belt and Road Initiative might appear benign and attractive, but not if the terms turn sour, as was recently the case in a Sri Lankan port project.

Likewise, other exercises of economic hard power undercut the soft power of China’s narrative. For example, China punished Norway for awarding a Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo (劉曉波). It also threatened to restrict access to the Chinese market for an Australian publisher of a book critical of China.

If we use the term sharp power as shorthand for information warfare, the contrast with soft power becomes plain. Sharp power is a type of hard power. It manipulates information, which is intangible, but intangibility is not the distinguishing characteristic of soft power. Verbal threats, for example, are both intangible and coercive.

When I introduced the concept of soft power in 1990, I wrote that it is characterized by voluntarism and indirection, while hard power rests on threats and inducements. If someone aims a gun at you, demands your money and takes your wallet, what you think and want is irrelevant. That is hard power. If he persuades you to give him your money, he has changed what you think and want. That is soft power.

Truth and openness create a dividing line between soft and sharp power in public diplomacy. When China’s official news agency, Xinhua, broadcasts openly in other countries, it is employing soft-power techniques, and we should accept that. When China Radio International covertly backs 33 radio stations in 14 countries, the boundary of sharp power has been crossed, and we should expose the breach of voluntarism.

Of course, advertising and persuasion always involve some degree of framing, which limits voluntarism, as do structural features of the social environment. However, extreme deception in framing can be viewed as coercive; though not violent, it prevents meaningful choice.

Techniques of public diplomacy that are widely viewed as propaganda cannot produce soft power. In an age of information, the scarcest resources are attention and credibility. That is why exchange programs that develop two-way communication and personal relations among students and young leaders are often far more effective generators of soft power than, say, official broadcasting.

The US has long had programs enabling visits by young foreign leaders, and now China is successfully following suit. That is a smart exercise of soft power, but when visas are manipulated or access is limited to restrain criticism and encourage self-censorship, even such exchange programs can gradually change into sharp power.

As democracies respond to China’s sharp power and information warfare, they have to be careful not to overreact. Much of the soft power democracies wield comes from civil society, which means that openness is a crucial asset.

China could generate more soft power if it would relax some of its tight party control over civil society. Similarly, manipulation of media and reliance on covert channels of communication often reduces soft power. Democracies should avoid the temptation to imitate these authoritarian sharp-power tools.

Moreover, shutting down legitimate Chinese soft-power tools can be counter-productive. Soft power is often used for competitive, zero-sum purposes — but it can also have positive sum aspects.

For example, if both China and the US wish to avoid conflict, exchange programs that increase US attraction to China and vice versa, would benefit both countries. On transnational issues such as climate change, where both countries can benefit from cooperation, soft power can help build the trust and create the networks that make such cooperation possible.

While it would be a mistake to prohibit Chinese soft-power efforts just because they sometimes change into sharp power, it is also important to monitor the dividing line carefully. For example, the Office of Chinese Language Council International, known as Hanban, is the government agency that manages the 500 Confucius Institutes and 1,000 Confucius classrooms that China supports in universities and schools around the world to teach Chinese language and culture. It must resist the temptation to set restrictions that limit academic freedom. Crossing that line has led to the disbanding of some Confucius Institutes.

As such cases show, the best defense against China’s use of soft-power programs as sharp-power tools is open exposure of such efforts, and this is where democracies have an advantage.

Joseph Nye is a former US assistant secretary of defense and chairman of the US National Intelligence Council, and a professor at Harvard University.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Is a new foreign partner for Taiwan emerging in the Middle East? Last week, Taiwanese media reported that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) secretly visited Israel, a country with whom Taiwan has long shared unofficial relations but which has approached those relations cautiously. In the wake of China’s implicit but clear support for Hamas and Iran in the wake of the October 2023 assault on Israel, Jerusalem’s calculus may be changing. Both small countries facing literal existential threats, Israel and Taiwan have much to gain from closer ties. In his recent op-ed for the Washington Post, President William

Taiwan-India relations appear to have been put on the back burner this year, including on Taiwan’s side. Geopolitical pressures have compelled both countries to recalibrate their priorities, even as their core security challenges remain unchanged. However, what is striking is the visible decline in the attention India once received from Taiwan. The absence of the annual Diwali celebrations for the Indian community and the lack of a commemoration marking the 30-year anniversary of the representative offices, the India Taipei Association and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Center, speak volumes and raise serious questions about whether Taiwan still has a coherent India

A stabbing attack inside and near two busy Taipei MRT stations on Friday evening shocked the nation and made headlines in many foreign and local news media, as such indiscriminate attacks are rare in Taiwan. Four people died, including the 27-year-old suspect, and 11 people sustained injuries. At Taipei Main Station, the suspect threw smoke grenades near two exits and fatally stabbed one person who tried to stop him. He later made his way to Eslite Spectrum Nanxi department store near Zhongshan MRT Station, where he threw more smoke grenades and fatally stabbed a person on a scooter by the roadside.

Recent media reports have again warned that traditional Chinese medicine pharmacies are disappearing and might vanish altogether within the next 15 years. Yet viewed through the broader lens of social and economic change, the rise and fall — or transformation — of industries is rarely the result of a single factor, nor is it inherently negative. Taiwan itself offers a clear parallel. Once renowned globally for manufacturing, it is now best known for its high-tech industries. Along the way, some businesses successfully transformed, while others disappeared. These shifts, painful as they might be for those directly affected, have not necessarily harmed society