An oil-field worker in a Gobi town posted poetry online memorializing the victims of the Tiananmen Square crackdown. An artist in Shanghai uploaded satirical photographs of his wincing visage superimposed on a portrait of the Chinese president. A civil rights lawyer in Beijing wrote microblog posts criticizing the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) handling of ethnic tensions.

In each case, the men were detained under a broad new interpretation of an established law the Chinese authorities are using to carry out the biggest crack down on Internet speech in many years.

Artists, essayists, lawyers, bloggers and others deemed to be online troublemakers have been hauled into police stations and investigated or imprisoned for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” a charge that was once confined to physical activities like handing out fliers or organizing protests.

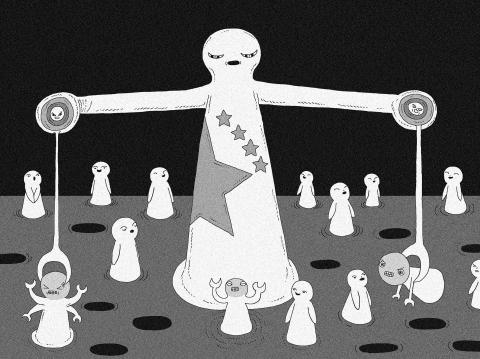

Illustration: Mountain People

The increasing use of that law to police online speech, which appears to have become more common in recent months, is part of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) strategy to deploy the legal code to silence dissent and clamp down on civil society.

Since a CCP conclave in October, when Xi and other leaders emphasized “rule of law,” the government has introduced a series of new laws to tighten the vise over civil society and rein in foreign organizations, which the party fears could help foment a revolution.

“The core of rule of law is that the government shall be restricted by law,” said Zhang Qianfan (張千帆), a law professor at Peking University. “Now it is using the law to punish whoever criticizes it or has some influence in the public realm.”

In March, five young feminists using social media to organize a campaign against sexual abuse were detained and initially investigated on the picking quarrels charge, setting off global outrage against China.

The latest wave of detentions of so-called provocateurs took place this month, when police officers across China rounded up more than 200 civil rights lawyers and their colleagues. Some remain in detention and may be charged with picking quarrels and other crimes.

An article in the People’s Daily, the flagship CCP newspaper, accused them of organizing protests and using instant messages to “engage in agitation and planning.” Global Times, a party-run tabloid, said the lawyers “often were no longer engaged in law, but in picking quarrels and provoking trouble with a plainly political slant.”

The legal definition of “picking quarrels” was expanded in late 2013 by the nation’s top legal bodies, the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, to encompass online behavior. The court said the charge could apply to anyone using information networks to “berate or intimidate others” and spread false information. First-time offenders can be sentenced up to five years in prison.

The Dui Hua Foundation, a human rights advocacy group based in San Francisco, said the interpretation was a “major elaboration” on the charge and that it treated online space “not only as a platform through which to incite others to disrupt social order but as a kind of public space itself that can be thrown into disorder by certain kinds of acts.”

The expanded interpretation also made unlawful any “defaming information” that is reposted 500 times or viewed 5,000 times, actions generally beyond the control of a post’s author. That definition was reiterated in the draft of a cybersecurity law released this month.

Dui Hua said in a March report that since the new interpretation took effect, “a growing list of Chinese people have been detained or charged for speech-related incidents” under the law. Among other things, the charge has been used to reinforce an “anti-rumor campaign” aimed at silencing people who question the official versions of news events.

Just days after the new interpretation was announced, 16-year-old Yang Hui (楊輝) was detained on the charge for having raised questions online about a police investigation into the death of a karaoke club manager.

As the government does not publicly report comprehensive judicial data, it is unclear precisely when the charge began to be widely used to restrict online speech.

“There do seem to be more cases of this coming to light, but I don’t think anyone can say with any certainty about statistics,” said Joshua Rosenzweig, a lecturer at the Chinese University of Hong Kong who studies the legal system. “There’s no transparency.”

He said security officials might prefer this charge because it might be easier to make a case for “picking quarrels” than for subversion of the state, another charge commonly used to punish political malcontents.

The wider interpretation, he said, was aimed at addressing the growing political discourse in cyberspace, which can at times feed into street actions.

“The boundaries between online space and physical space were beginning to get blurred,” he said. “The authorities needed to respond to this in new ways.”

The best-known “picking quarrels” case is that of 50-year-old Pu Zhiqiang (蒲志強), a burly, baritone-voiced civil rights defense lawyer who has been held by the police for more than one year without a trial. In May, prosecutors brought two charges against him: inciting ethnic hatred, and picking quarrels and provoking trouble, for which he faces up to eight years in prison.

Pu’s lawyers said the prosecutors had built their case on 28 posts he had written on Weibo, a microblog platform. Lawyer Shang Baojun (尚寶軍) said prosecutors had not laid out their evidence in detail, but the ethnic hatred charge seemed to apply to posts Pu wrote after a knife attack at the Kunming train station in 2014 in which ethnic Uighurs killed 31 people. Pu said Chinese policies in the western region of Xinjiang, where most Uighurs live, were partly to blame. “If you say Xinjiang belongs to China, don’t treat it as a colony,” he wrote.

As for the picking quarrels charge, Shang said it was hard to tell which posts would be used as evidence since the charge “is so broad.”

“It may include his posts questioning some public figures and the meeting concerning June 4,” Shang said, referring to a private gathering in Beijing that Pu attended in May last year to commemorate the June 4, 1989, crackdown around Tiananmen Square. Pu was detained after that meeting.

Though Pu is suffering from prostatitis, no one is allowed to give him medicine, Shang said. He walks about two hours a day inside his cell to try to alleviate the pain. Officials have rejected applications for medical bail. He has undergone 10-hour interrogation sessions and has been denied timely access to his lawyers, Shang said.

Not everyone detained on the picking quarrels charge is such an outspoken critic of the system. Dai Jianyong (戴建勇), a conceptual artist in Shanghai, is known for taking photographs of himself with his eyes tightly shut in a wincing face.

His fans call him “Chrysanthemum Face,” which also means “Anus Face” in Chinese. His online photo albums show him making that face while standing next to the Statue of Liberty, Facebook headquarters in Silicon Valley and models at a Shanghai car show.

However, the photo that crossed the line was one that digitally merged his face with that of Xi. Dai was detained in late May after he posted the new photograph online. He had also posted a sticker print of the photo outside the Shanghai Sculpture Space, a gallery near his home.

“My husband loves photography,” his wife, Zhu Fengjuan (朱鳳娟), said in an interview shortly after his detention. “Apart from that, he has done nothing.”

Dai was released from jail last month but remains under surveillance. He and Zhu have declined to be interviewed since then.

The case of Nie Zhanye (聶占業) was more overtly linked to political speech. The police arrested him in June last year on suspicion of inciting subversion. Prosecutors said he had disseminated articles honoring the Tiananmen Square victims to nearly 11,000 people in dozens of chat groups. In January, Nie, 50, who works in oil exploration, was convicted on the charge of picking quarrels solely for his online posts.

A court sentenced him to three years in prison, but he has been allowed to live at home under surveillance.

A poem by another author that Nie posted on the Internet last year said: “They used to crush students with armored vehicles. Nowadays, they are ready to launch a full-scale war against their people by maintaining stability.”

The gutting of Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) by US President Donald Trump’s administration poses a serious threat to the global voice of freedom, particularly for those living under authoritarian regimes such as China. The US — hailed as the model of liberal democracy — has the moral responsibility to uphold the values it champions. In undermining these institutions, the US risks diminishing its “soft power,” a pivotal pillar of its global influence. VOA Tibetan and RFA Tibetan played an enormous role in promoting the strong image of the US in and outside Tibet. On VOA Tibetan,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,

US President Trump weighed into the state of America’s semiconductor manufacturing when he declared, “They [Taiwan] stole it from us. They took it from us, and I don’t blame them. I give them credit.” At a prior White House event President Trump hosted TSMC chairman C.C. Wei (魏哲家), head of the world’s largest and most advanced chip manufacturer, to announce a commitment to invest US$100 billion in America. The president then shifted his previously critical rhetoric on Taiwan and put off tariffs on its chips. Now we learn that the Trump Administration is conducting a “trade investigation” on semiconductors which

By now, most of Taiwan has heard Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an’s (蔣萬安) threats to initiate a vote of no confidence against the Cabinet. His rationale is that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)-led government’s investigation into alleged signature forgery in the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) recall campaign constitutes “political persecution.” I sincerely hope he goes through with it. The opposition currently holds a majority in the Legislative Yuan, so the initiation of a no-confidence motion and its passage should be entirely within reach. If Chiang truly believes that the government is overreaching, abusing its power and targeting political opponents — then