Early one morning in late April, Parvinder Hundal stood beside a hole in the ground at the edge of his almond farm near Tulare in California’s Central Valley.

The hole, which was about the size of a volleyball and was encased in a shallow block of concrete, was the opening of a well, one that went hundreds of feet into the earth. He had paid US$100,000 to have it drilled, but it was not producing water. Hundal was hoping that if he cleaned out the well, the water would start flowing again.

On the nearby trees, some leaves had turned yellow, and the almond husks appeared smaller than usual.

In February, Hundal received e-mails from various water districts, informing him that, because of a historic drought that has left reservoirs nearly dry, he would most likely get no surface water to irrigate his 1,619 hectares of crops this summer. Not one drop.

Hundal watched as his nephew, his right-hand man, prepared to lower pipe into the hole.

“We’ll have water by the end of the day, I hope,” Hundal said.

Hundal is an optimist. An immigrant from Punjab in northwest India, he arrived in California in 1986 with little money, and, through a combination of borrowing and shrewdness, he managed to make a small fortune through farming.

However, he is also a pragmatist. Since he cannot count on the virtually unlimited surface water he has been allotted in the past, he is been looking for water underground.

This year, Hundal spent US$300,000 to hire a contractor to dig three wells, including the one in Tulare. Those did not pan out. So he wired US$670,000 to a broker in Texas to buy his own used drill. No water, no problem. Hundal will drill when he wants.

There is a well-drilling boom in the Central Valley, and it is a water grab as intense as any land grab before it. Drilling contractors are so swamped with requests that there is a wait of between four and six months for a new well. Drilling permits are soaring.

In Tulare County, home to several of Hundal’s almond farms, 660 permits for new irrigation wells were taken out by the end of this April, up from 383 during the same period last year and just 60 five years ago — a figure rising “exponentially,” Tulare County Health and Human Services Agency spokeswoman Tammie Weyker said.

‘IT’S ABOUT SURVIVAL’

The new drill that Hundal ordered from Texas should be up and running in a few weeks. He says it can push 762m into the ground, tapping new aquifers and making way for wells that can produce thousands of liters of water a minute. He plans to drill at least six wells on his various farms across the Central Valley: Four of them are in Tulare, and two are on property 160km north.

“It’s about survival,” he said. “Everybody is pulling water out of the ground.”

“Nobody is bothered,” he added. “The neighbors aren’t bothered. Everybody is doing what they’ve got to do.”

It turns out, though, that some people are bothered — very bothered — and are growing hostile. That is because the drilling has serious side effects. Rampant drilling causes underground water levels to fall. When shallow farm and domestic wells that serve residences dry up, the underground bounty goes to those who can afford to dig deeper.

When it comes to drilling for water, there are few rules and no boundaries. Generally, farmers who follow a set of modest regulations can drill on their own land.

California passed stronger regulations last year that are intended to govern underground drilling. Details of the rules are still being worked out.

However, even then, the rules will not have any real effect for 25 years or more, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory senior water scientist Jay Famiglietti said.

“You drill a well on your property; you draw it out, even if it means you draw from under your neighbor’s property,” he says. “You’re drawing water from every direction.”

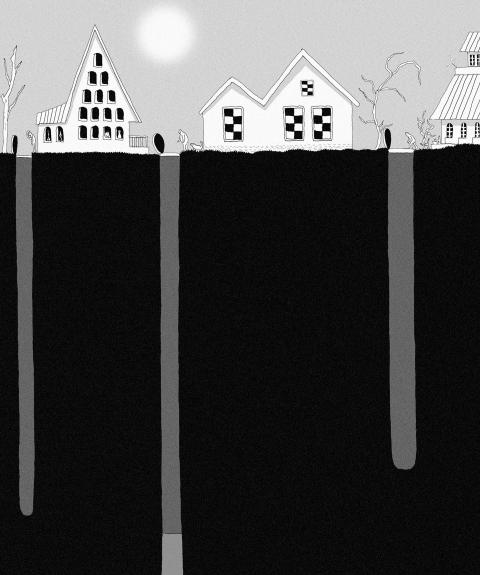

Underground water supply is not fenced or restricted; it is moisture held in the soil, rocks and clay and drawn through wells like a soft drink through a straw.

In a normal year, 33 percent of California’s water comes from underground, but this year, it is expected to approach 75 percent, Famiglietti says. Since 2011, the state has lost 30.3 trillion liters from its overall water reserves, two-thirds of that from its underground aquifers, he says.

“We can’t keep doing this,” Famiglietti says.

The draining of the aquifers creates another hazard above ground. As water is pulled from the spongy layers below, the ground above collapses, creating what is known as subsidence.

Where subsidence is the worst, the land can sink as much as 30.5cm each year.

Water scarcity and buckling land have neighboring farmers eyeing one another warily.

Relations are fraying, with the drilling threatening to revive tensions that have been subdued for half a century or more, when farmers last relied so heavily on groundwater, says Gary Sawyers, a prominent lawyer on water rights in the region.

However, now, with the expansion of agriculture in the Central Valley and the planting of thirsty, year-round crops like almonds, the demand for water is much greater.

“It’s the same situation as 60 or 70 years ago, but squared, or on steroids,” Sawyers says.

MORE THAN GOLD

On Aug. 18, 1962, then-US president John F. Kennedy landed in a helicopter near an enormous dusty bowl in the northern Central Valley. He had come for a groundbreaking ceremony at the future site of the San Luis Reservoir, which would eventually store hundreds of billions of gallons of the water from the Sierra Nevada to the north.

Speaking from beneath an ornate tent to hundreds of sunbaked listeners, Kennedy said that coming to the area, he could see “the greenest and richest earth producing the greatest and richest crops in the country and then, a mile away, see the same earth and see it brown and dusty and useless — all because there’s water in one place, and there isn’t in another.”

The construction in 1963 of the California Aqueduct system changed all that. Before it was built, farmers had relied on wells for their water, which led to the land collapsing.

The surface water irrigation meant less pumping and led to “widespread groundwater recoveries, and subsidence essentially ceased in many areas,” US Geological Survey senior scientist Michelle Sneed said.

Scarcity of water has always been an issue in the Central Valley; this part of the valley gets only about 25cm of rain a year. A German immigrant named Henry Miller, who was a pioneer in the region in the latter half of the 1800s, developed a system of canals and founded the region’s first irrigation company for farmers.

A legend, he was called the Cattle King of California, and he “realized early on that water was ultimately of higher value than gold in California,” according to a biography edited by the German Historical Institute.

The value of water has become acutely real to Miller’s great-great-great-grandson, Cannon Michael, who is the president of the Bowles Farming Co.

Tall and well-spoken, Michael is the product of an elite boarding school and the University of California, Berkeley, where he majored in English. After 15 years working at Bowles — which has US$25 million in annual sales, about 15 percent of that profit — he became president of the family enterprise just last year.

It was not the easiest time to take charge.

Sitting at a conference table in his ranch-style offices, Michael displayed a Google Earth map on a large monitor on the wall. The map showed the area in and around his 4,249 hectare farm, not far from the San Luis Reservoir, in the northern part of the Central Valley — much closer to Silicon Valley than to Los Angeles.

On the map, some areas were yellow, others red.

Yellow areas had suffered moderate subsidence, he said.

Red meant real trouble; in some of those red areas, the land had been dropping nearly a 30cm a year, on average, since 2008. Near the bottom of the map was a spot swirling with yellow and red: Sack Dam.

“That’s our diversion point,” Michael said.

Sack Dam is the place on the San Joaquin River where surface water finishes its long journey from the north and is diverted onto the farms of Michael and his neighbors.

Because Michael’s farm is a parcel from the Miller farm, established in 1858, he has high-priority access to surface water. That is particularly important now because, in times of scarcity, these senior water-rights holders — generally, farms established before 1914 — get their water allotment before farms with lower-priority rights, like those owned by Hundal.

SUBSIDENCE

However, now there is a problem for all the farmers, no matter what rights they have to surface water: Heavy drilling by farmers near Sack Dam is causing the land to cave in so much that the water is having trouble taking its normal path.

Further subsidence will make it hard for water to get through Sack Dam to Michael’s farm and those of his neighbors.

“Water traditionally flowed with gravity,” as Michael put it. “It isn’t going to run uphill.”

One of the hundreds of farms in the Sack Dam area belongs to Hundal. He and Michael have never met, so in one sense, there is no particular connection between them, but like all the farmers in the region, they are connected by water.

This year, thanks to his senior status, Michael will get surface water, about 50 percent of his usual amount, a hardship that means fallowing about 1,012 hectares of wheat, cotton, alfalfa and tomato fields.

By happenstance, the water that he and his neighbors get this year comes from a source that historically supplied the lower-priority water rights holders in Tulare. Those farmers, including Hundal, will not get any water.

Another connection between these farmers has to do with subsidence, as Michael showed on his map.

He found Hundal’s farm, about 32km northeast of Sack Dam. It was colored yellow and red to signify heavy subsidence, and the stream of color connected all the way down to Michael’s diversion point.

Michael does not rebuke Hundal or others for drilling.

“You take away a guy’s surface water and he’s going to do what he has to do to survive,” he said.

However, his tone hardened when he talked about what could amount to a US$10 million bill to install a pump to push the water uphill at Sack Dam if the subsidence worsens.

“We could make a legal case that these folks are causing the issue,” he said of the farmers who are drilling near the dam.

That sentiment is shared by a number of the senior water rights holders, said Chase Hurley, the manager of the San Luis Canal Co, which manages water for about 18,211 hectares, including Michael’s land.

Hurley says the farmers with senior rights have been rumbling about a way to “get this thing straightened out” or else go after the other farmers in court. They are focused on drillers within about 8km of the dam.

Hurley tells them they do not have a very good legal case.

“Based on current California law, you can dig as many holes as you want,” he said.

Besides, he adds, which landowners would they sue? Farmers whose land borders Sack Dam or those a few kilometers out, like Hundal?

Geology is not neat, and the underground aquifer is like a giant earthy sponge, Sneed said.

And not all the holes in the sponge connect; sometimes, drilling in one well might drain a hole at a distance and not affect one nearby.

There is no simple way, she says, to trace a crater to the particular well that sucked the groundwater out of it.

TAKING WHAT THEY CAN

Hundal, 57, drove me around his farms in his Ford F-250 pickup truck and described growing up on a farm in India, getting a college degree and immigrating to San Francisco.

Seven years after he arrived, he had a master’s degree in agronomy from Chico State and 8 hectares.

Then, a few years later, he bought 36.4 hectares — “that was a really risky step,” he said.

He smiled at the audacity.

He said he borrowed the US$650,000 for the new land and grew almonds, long before it was common to do so.

Now he takes in US$14 million in sales from his collection of farms, mostly almond orchards. He hires 25 farmworkers from February through October, but still tends to a lot himself, using a jury-rigged tractor to plant almond and cherry trees. He and his wife recently bought a second home at Pebble Beach for US$8 million.

I told him that some of the farmers with senior water rights have talked about suing farmers drilling near the dam — not Hundal necessarily, but maybe ones closer to Sack Dam.

“They can do that,” but it would be a “waste of time in court,” he said, kicking a cloud of dust.

Sawyers — who works for farmers on both sides of Sack Dam — says that a lawsuit over subsidence could be the first of its kind.

He could not recall another.

However, neither has there been such a drought in recent history.

“The current circumstances may give rise to all kinds of new lawsuits,” he said.

This is not to say a lawsuit is imminent or even likely. Hurley has helped the farmers with senior water rights try diplomacy. Their group has spent US$250,000 to help the districts to the east study how to fix the subsidence.

NEW TENSIONS

Farmers on both sides of the dam have talked of jointly developing an underground reservoir that would be replenished with floodwaters, but floodwaters, even under normal climate conditions, are released only about every four years, Hurley said.

Other possible solutions, like using pipes to connect farms, so they can share water more efficiently, could also take years.

Many farmers in the Central Valley agree on a collection of nemeses that includes the news media, regulators and environmentalists, but now there are new tensions.

Chris Hurd, a farmer in the region for three decades, still contends that environmental interests and regulators are most to blame for water scarcity, but he said that comity among farmers has started to fray.

“The infighting that’s going on is going to get real bad,” he said.

It is “one year at a time,” he said of farmers’ mindset. “Most guys can make money if they can figure out how to get things wet the next 120 days.”

“Guys are overdrafting right next to each other,” he said of the water drilling, adding that he recently saw one farmer’s wells go dry just days after a farmer 800km away put in a deeper well.

However, “what’s going to drive it to the forefront is not farmer losses, but when a lot of domestic wells will go dry this summer,” he said.

RACE TO DRILL DEEPER

What is bad for California farmers is turning out to be good for Michael Higgins. He owns Summit Power & Supply, a company in Austin, Texas, that buys and sells drilling equipment, for water and oil wells. He gets six calls a week from Golden State farmers, up from one every two months just two years ago.

“They’re getting frantic,” Higgins said.

When Hundal went to Texas to shop for drills, he discovered something remarkable: Higgins’ customers were familiar names.

“I knew everybody,” Hundal said. “It was amazing.”

Two simple, if contradictory, themes have emerged among farmers: One, we are all in this together. Two, it is every man for himself.

Steve Laird, who has a small farm in the area, put it this way: “When it comes down to it, it’s either mine or yours. You do what you have to do to survive.”

Hundal’s new drill arrived from Texas in the middle of last month.

Then another challenge arose: He had reached a handshake agreement with a licensed driller to operate the drill, but the driller started “dragging his feet,” Hundal said.

Hundal suspected the reason.

“He wants big money. He smells that,” the farmer said. “I can’t drill without a license.”

As he waited to start drilling a new well, Hundal discovered that his neighbor was also drilling across the street, just 30m away.

Hundal thought it was possible that the neighbor’s well would suck up his water.

“It’s crazy, but I can’t tell him to drill away from me,” Hundal said. “It’s his land, not mine.”

If his well goes dry, “I’ll have to drill another one and go a little deeper,” Hundal said.

The gutting of Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) by US President Donald Trump’s administration poses a serious threat to the global voice of freedom, particularly for those living under authoritarian regimes such as China. The US — hailed as the model of liberal democracy — has the moral responsibility to uphold the values it champions. In undermining these institutions, the US risks diminishing its “soft power,” a pivotal pillar of its global influence. VOA Tibetan and RFA Tibetan played an enormous role in promoting the strong image of the US in and outside Tibet. On VOA Tibetan,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,

US President Trump weighed into the state of America’s semiconductor manufacturing when he declared, “They [Taiwan] stole it from us. They took it from us, and I don’t blame them. I give them credit.” At a prior White House event President Trump hosted TSMC chairman C.C. Wei (魏哲家), head of the world’s largest and most advanced chip manufacturer, to announce a commitment to invest US$100 billion in America. The president then shifted his previously critical rhetoric on Taiwan and put off tariffs on its chips. Now we learn that the Trump Administration is conducting a “trade investigation” on semiconductors which

By now, most of Taiwan has heard Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an’s (蔣萬安) threats to initiate a vote of no confidence against the Cabinet. His rationale is that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)-led government’s investigation into alleged signature forgery in the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) recall campaign constitutes “political persecution.” I sincerely hope he goes through with it. The opposition currently holds a majority in the Legislative Yuan, so the initiation of a no-confidence motion and its passage should be entirely within reach. If Chiang truly believes that the government is overreaching, abusing its power and targeting political opponents — then